Natural Products with Activity against Lung Cancer: A Review Focusing on the Tumor Microenvironment

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Effects of Natural Products on the Tumor Microenvironment

2.1. Natural Products Involved in Angiogenesis Inhibition

2.2. Natural Products Control ECM Degradation

2.3. Natural Products Reduce the Accumulation of MDSCs

2.4. Natural Products Regulate TAMs

2.5. Natural Products as Important Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

3. Combination of Natural Products and Anticancer Drugs

4. Combination of Natural Products with Nanotechnology or Other Materials for Targeting the TME

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.D.; Nogueira, L.; Mariotto, A.B.; Rowland, J.H.; Yabroff, K.R.; Alfano, C.M.; Jemal, A.; Kramer, J.L.; Siegel, R.L. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mittal, V.; El Rayes, T.; Narula, N.; McGraw, T.E.; Altorki, N.K.; Barcellos-Hoff, M.H. The Microenvironment of Lung Cancer and Therapeutic Implications. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016, 890, 75–110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Altorki, N.K.; Markowitz, G.J.; Gao, D.; Port, J.L.; Saxena, A.; Stiles, B.; McGraw, T.; Mittal, V. The lung microenvironment: An important regulator of tumour growth and metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2019, 19, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hanahan, D.; Coussens, L.M. Accessories to the crime: Functions of cells recruited to the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell 2012, 21, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, Z.; Fillmore, C.M.; Hammerman, P.S.; Kim, C.F.; Wong, K.K. Non-small-cell lung cancers: A heterogeneous set of diseases. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quail, D.F.; Joyce, J.A. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1423–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs over the Nearly Four Decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 770–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Zhang, S.Q.; Liu, L.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Y.X.; Xie, L.P.; Liu, J.C. Jolkinolide A and Jolkinolide B Inhibit Proliferation of A549 Cells and Activity of Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells. Med. Sci. Monit. 2017, 23, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Talib, W.H.; Al Kury, L.T. Parthenolide inhibits tumor-promoting effects of nicotine in lung cancer by inducing P53-dependent apoptosis and inhibiting VEGF expression. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 107, 1488–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Lee, H.J.; Jeong, S.J.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, E.O.; Kim, H.S.; Zhang, Y.; Ryu, S.Y.; Lee, M.H.; Lu, J.; et al. Galbanic acid isolated from Ferula assafoetida exerts in vivo anti-tumor activity in association with anti-angiogenesis and anti-proliferation. Pharm. Res. 2011, 28, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, Y.; Qing, C. Anti-angiogenic activity of salvicine. Pharm. Biol. 2013, 51, 1061–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xie, J.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Liang, S.; Lin, M.; Gu, Y.; Liu, T.; Wang, D.; Ge, H.; Mo, S.L. The antitumor effect of tanshinone IIA on anti-proliferation and decreasing VEGF/VEGFR2 expression on the human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cell line. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2015, 5, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Komi, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Shimamura, M.; Kajimoto, S.; Nakajo, S.; Masuda, M.; Shibuya, M.; Itabe, H.; Shimokado, K.; Oettgen, P.; et al. Mechanism of inhibition of tumor angiogenesis by beta-hydroxyisovalerylshikonin. Cancer Sci. 2009, 100, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Peng, A.; He, S.; Shao, X.; Nie, C.; Chen, L. Isogambogenic acid inhibits tumour angiogenesis by suppressing Rho GTPases and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 signalling pathway. J. Chemother 2013, 25, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Korbel, C.; Scheuer, C.; Nenicu, A.; Menger, M.D.; Laschke, M.W. Tubeimoside-1 suppresses tumor angiogenesis by stimulation of proteasomal VEGFR2 and Tie2 degradation in a non-small cell lung cancer xenograft model. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 5258–5272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jung, M.H.; Lee, S.H.; Ahn, E.M.; Lee, Y.M. Decursin and decursinol angelate inhibit VEGF-induced angiogenesis via suppression of the VEGFR-2-signaling pathway. Carcinogenesis 2009, 30, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.H.; Choi, S.; Lee, Y.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, K.H.; Ahn, K.S.; Bae, H.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, E.O.; Ahn, K.S.; et al. Herbal compound farnesiferol C exerts antiangiogenic and antitumor activity and targets multiple aspects of VEGFR1 (Flt1) or VEGFR2 (Flk1) signaling cascades. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2010, 9, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Takaku, T.; Kimura, Y.; Okuda, H. Isolation of an antitumor compound from Agaricus blazei Murill and its mechanism of action. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 1409–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandakumar, V.; Singh, T.; Katiyar, S.K. Multi-targeted prevention and therapy of cancer by proanthocyanidins. Cancer Lett. 2008, 269, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharma, S.D.; Meeran, S.M.; Katiyar, S.K. Dietary grape seed proanthocyanidins inhibit UVB-induced oxidative stress and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases and nuclear factor-kappaB signaling in in vivo SKH-1 hairless mice. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2007, 6, 995–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Risau, W. Differentiation of endothelium. FASEB J. 1995, 9, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Choi, D.S.; Lee, O.H.; Oh, S.H.; Lippman, S.M.; Lee, H.Y. Antiangiogenic antitumor activities of IGFBP-3 are mediated by IGF-independent suppression of Erk1/2 activation and Egr-1-mediated transcriptional events. Blood 2011, 118, 2622–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Akhtar, S.; Meeran, S.M.; Katiyar, N.; Katiyar, S.K. Grape seed proanthocyanidins inhibit the growth of human non-small cell lung cancer xenografts by targeting insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3, tumor cell proliferation, and angiogenic factors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 821–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khan, N.; Afaq, F.; Kweon, M.H.; Kim, K.; Mukhtar, H. Oral consumption of pomegranate fruit extract inhibits growth and progression of primary lung tumors in mice. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 3475–3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Feng, J.; Xu, R.; Dou, Y. Extracts from Huangqi (Radix Astragali Mongoliciplus) and Ezhu (Rhizoma Curcumae Phaeocaulis) inhibit Lewis lung carcinoma cell growth in a xenograft mouse model by impairing mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling, vascular endothelial growth factor production, and angiogenesis. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2019, 39, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shiau, A.L.; Shen, Y.T.; Hsieh, J.L.; Wu, C.L.; Lee, C.H. Scutellaria barbata inhibits angiogenesis through downregulation of HIF-1 alpha in lung tumor. Environ. Toxicol. 2014, 29, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Cao, C.; Su, Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Chen, H.; Xu, A. Ginkgo biloba exocarp extracts inhibits angiogenesis and its effects on Wnt/beta-catenin-VEGF signaling pathway in Lewis lung cancer. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 192, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Yang, G.Y.; Park, E.S.; Meng, X.; Sun, Y.; Jia, D.; Seril, D.N.; Yang, C.S. Inhibition of lung carcinogenesis and effects on angiogenesis and apoptosis in A/J mice by oral administration of green tea. Nutr. Cancer 2004, 48, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, L.; Wang, J.N.; Cao, X.Q.; Sun, C.X.; Du, X. An-te-xiao capsule inhibits tumor growth in non-small cell lung cancer by targeting angiogenesis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 108, 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Y. Influence of erbanxiao solution on inhibiting angiogenesis in stasis toxin stagnation of non-small cell lung cancer. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2013, 33, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, H.J.; Lee, E.O.; Rhee, Y.H.; Ahn, K.S.; Li, G.X.; Jiang, C.; Lu, J.; Kim, S.H. An oriental herbal cocktail, ka-mi-kae-kyuk-tang, exerts anti-cancer activities by targeting angiogenesis, apoptosis and metastasis. Carcinogenesis 2006, 27, 2455–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xie, B.; Xie, X.; Rao, B.; Liu, S.; Liu, H. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying the Inhibitory Effects of Qingzaojiufei Decoction on Tumor Growth in Lewis Lung Carcinoma. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, J.; Han, R.; Li, J.; Zhai, L.; Xie, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Luo, J.; Wang, S.; Sun, Z.; et al. Analysis of Molecular Mechanism of YiqiChutan Formula Regulating DLL4-Notch Signaling to Inhibit Angiogenesis in Lung Cancer. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 8875503. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liao, H.; Wang, Z.; Deng, Z.; Ren, H.; Li, X. Curcumin inhibits lung cancer invasion and metastasis by attenuating GLUT1/MT1-MMP/MMP2 pathway. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 8948–8957. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pai, J.T.; Hsu, C.Y.; Hsieh, Y.S.; Tsai, T.Y.; Hua, K.T.; Weng, M.S. Suppressing migration and invasion of H1299 lung cancer cells by honokiol through disrupting expression of an HDAC6-mediated matrix metalloproteinase 9. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 1534–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sazuka, M.; Imazawa, H.; Shoji, Y.; Mita, T.; Hara, Y.; Isemura, M. Inhibition of collagenases from mouse lung carcinoma cells by green tea catechins and black tea theaflavins. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1997, 61, 1504–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chakrawarti, L.; Agrawal, R.; Dang, S.; Gupta, S.; Gabrani, R. Therapeutic effects of EGCG: A patent review. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2016, 26, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.T.; Lin, J.K. EGCG inhibits the invasion of highly invasive CL1-5 lung cancer cells through suppressing MMP-2 expression via JNK signaling and induces G2/M arrest. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 13318–13327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Liu, F.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Lin, B.; Tang, X. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits nicotine-induced migration and invasion by the suppression of angiogenesis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 33, 2972–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- He, H.; Zheng, L.; Sun, Y.P.; Zhang, G.W.; Yue, Z.G. Steroidal saponins from Paris polyphylla suppress adhesion, migration and invasion of human lung cancer A549 cells via down-regulating MMP-2 and MMP-9. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 10911–10916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, S.; Chaugule, S.; More, S.; Rane, G.; Indap, M. Methanolic extract of Euchelus asper exhibits in-ovo anti-angiogenic and in vitro anti-proliferative activities. Biol. Res. 2017, 50, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tseng, H.H.; Chen, P.N.; Kuo, W.H.; Wang, J.W.; Chu, S.C.; Hsieh, Y.S. Antimetastatic potentials of Phyllanthus urinaria L on A549 and Lewis lung carcinoma cells via repression of matrix-degrading proteases. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2012, 11, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lim, W.C.; Choi, H.K.; Kim, K.T.; Lim, T.G. Rose (Rosa gallica) Petal Extract Suppress Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion of Human Lung Adenocarcinoma A549 Cells through via the EGFR Signaling Pathway. Molecules 2020, 25, 5119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.F.; Chu, S.C.; Hsieh, Y.H.; Chen, P.N.; Hsieh, Y.S. Viola Yedoensis Suppresses Cell Invasion by Targeting the Protease and NF-kappaB Activities in A549 and Lewis Lung Carcinoma Cells. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 15, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, H.C.; Horng, C.T.; Lee, Y.L.; Chen, P.N.; Lin, C.Y.; Liao, C.Y.; Hsieh, Y.S.; Chu, S.C. Cinnamomum Cassia Extracts Suppress Human Lung Cancer Cells Invasion by Reducing u-PA/MMP Expression through the FAK to ERK Pathways. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 15, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, P.N.; Yang, S.F.; Yu, C.C.; Lin, C.Y.; Huang, S.H.; Chu, S.C.; Hsieh, Y.S. Duchesnea indica extract suppresses the migration of human lung adenocarcinoma cells by inhibiting epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Environ. Toxicol. 2017, 32, 2053–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.J.; Liu, T.; Mao, X.; Han, S.X.; Liang, R.X.; Hui, L.Q.; Cao, C.Y.; You, Y.; Zhang, L.Z. Fructus phyllanthi tannin fraction induces apoptosis and inhibits migration and invasion of human lung squamous carcinoma cells in vitro via MAPK/MMP pathways. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2015, 36, 758–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Im, I.; Park, K.R.; Kim, S.M.; Kim, C.; Park, J.H.; Nam, D.; Jang, H.J.; Shim, B.S.; Ahn, K.S.; Mosaddik, A.; et al. The butanol fraction of guava (Psidium cattleianum Sabine) leaf extract suppresses MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression and activity through the suppression of the ERK1/2 MAPK signaling pathway. Nutr. Cancer 2012, 64, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.C.; Yang, S.F.; Liu, S.J.; Kuo, W.H.; Chang, Y.Z.; Hsieh, Y.S. In vitro and in vivo antimetastatic effects of Terminalia catappa L. leaves on lung cancer cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2007, 45, 1194–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, S.; Gao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, L.; Ma, C.; Liu, C.; Huang, L. Antitumor and antimetastatic activities of Rhizoma Paridis saponins. Steroids 2009, 74, 1051–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.F.; Chu, S.C.; Liu, S.J.; Chen, Y.C.; Chang, Y.Z.; Hsieh, Y.S. Antimetastatic activities of Selaginella tamariscina (Beauv.) on lung cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 110, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.C.; Magesh, V.; Jeong, S.J.; Lee, H.J.; Ahn, K.S.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, E.O.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, M.H.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Ethanol extract of Ocimum sanctum exerts anti-metastatic activity through inactivation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and enhancement of anti-oxidant enzymes. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010, 48, 1478–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shia, C.S.; Suresh, G.; Hou, Y.C.; Lin, Y.C.; Chao, P.D.; Juang, S.H. Suppression on metastasis by rhubarb through modulation on MMP-2 and uPA in human A549 lung adenocarcinoma: An ex vivo approach. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 133, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, S.; Yang, X.; Long, S.; Xiao, S.; Wu, W.; Hann, S.S. Traditional Chinese medicine, Fuzheng KangAi decoction, inhibits metastasis of lung cancer cells through the STAT3/MMP9 pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 2461–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Qi, Q.; Hou, Y.; Li, A.; Sun, Y.; Li, S.; Zhao, Z. Yifei Tongluo, a Chinese Herbal Formula, Suppresses Tumor Growth and Metastasis and Exerts Immunomodulatory Effect in Lewis Lung Carcinoma Mice. Molecules 2019, 24, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhao, Y.; Shao, Q.; Zhu, H.; Xu, H.; Long, W.; Yu, B.; Zhou, L.; Xu, H.; Wu, Y.; Su, Z. Resveratrol ameliorates Lewis lung carcinoma-bearing mice development, decreases granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cell accumulation and impairs its suppressive ability. Cancer Sci. 2018, 109, 2677–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, T.; Liu, W.; Guo, W.; Zhu, X. Silymarin suppressed lung cancer growth in mice via inhibiting myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 81, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloc, M.; Ghobrial, R.M.; Lipinska-Opalka, A.; Wawrzyniak, A.; Zdanowski, R.; Kalicki, B.; Kubiak, J.Z. Effects of vitamin D on macrophages and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) hyperinflammatory response in the lungs of COVID-19 patients. Cell Immunol. 2021, 360, 104259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, X.; Wu, X. Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharide (GLP) enhances antitumor immune response by regulating differentiation and inhibition of MDSCs via a CARD9-NF-kappaB-IDO pathway. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20201170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, K.; Tian, J.; Tang, X.; Ma, J.; Xu, P.; Tian, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, H.; Lu, L.; Wang, S. Curdlan blocks the immune suppression by myeloid-derived suppressor cells and reduces tumor burden. Immunol. Res. 2016, 64, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.H.; Zhu, Y.Z.; Su, L.; Tang, X.Y.; Yao, C.; Jiao, X.N.; Hou, Y.F.; Chen, X.; Wei, L.Y.; Wang, W.T.; et al. Ze-Qi-Tang Formula Induces Granulocytic Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cell Apoptosis via STAT3/S100A9/Bcl-2/Caspase-3 Signaling to Prolong the Survival of Mice with Orthotopic Lung Cancer. Mediators Inflamm. 2021, 2021, 8856326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.C.; Chan, M.L.; Chen, M.J.; Tsai, T.H.; Chen, Y.J. Modulation of macrophage polarization and lung cancer cell stemness by MUC1 and development of a related small-molecule inhibitor pterostilbene. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 39363–39375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, C.Y.; Cherng, J.Y.; Yang, Y.H.; Lin, C.L.; Kuan, F.C.; Lin, Y.Y.; Lin, Y.S.; Shu, L.H.; Cheng, Y.C.; Liu, H.T.; et al. Danshen improves survival of patients with advanced lung cancer and targeting the relationship between macrophages and lung cancer cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 90925–90947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Huang, N.; Zhu, W.; Wu, J.; Yang, X.; Teng, W.; Tian, J.; Fang, Z.; Luo, Y.; Chen, M.; et al. Modulation the crosstalk between tumor-associated macrophages and non-small cell lung cancer to inhibit tumor migration and invasion by ginsenoside Rh2. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyiramana, M.M.; Cho, S.B.; Kim, E.J.; Kim, M.J.; Ryu, J.H.; Nam, H.J.; Kim, N.G.; Park, S.H.; Choi, Y.J.; Kang, S.S.; et al. Sea Hare Hydrolysate-Induced Reduction of Human Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cell Growth through Regulation of Macrophage Polarization and Non-Apoptotic Regulated Cell Death Pathways. Cancers 2020, 12, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, L.; Wu, W.; Zhu, X.; Ng, W.; Gong, C.; Yao, C.; Ni, Z.; Yan, X.; Fang, C.; Zhu, S. The Ancient Chinese Decoction Yu-Ping-Feng Suppresses Orthotopic Lewis Lung Cancer Tumor Growth Through Increasing M1 Macrophage Polarization and CD4(+) T Cell Cytotoxicity. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pang, L.; Han, S.; Jiao, Y.; Jiang, S.; He, X.; Li, P. Bu Fei Decoction attenuates the tumor associated macrophage stimulated proliferation, migration, invasion and immunosuppression of non-small cell lung cancer, partially via IL-10 and PD-L1 regulation. Int. J. Oncol. 2017, 51, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rawangkan, A.; Wongsirisin, P.; Namiki, K.; Iida, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Shimizu, Y.; Fujiki, H.; Suganuma, M. Green Tea Catechin Is an Alternative Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor that Inhibits PD-L1 Expression and Lung Tumor Growth. Molecules 2018, 23, 2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, N.; Yin, M.; Dong, J.; Zeng, Q.; Mao, G.; Song, D.; Liu, L.; Deng, H. Berberine diminishes cancer cell PD-L1 expression and facilitates antitumor immunity via inhibiting the deubiquitination activity of CSN5. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2020, 10, 2299–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Yang, J.; Qu, L.; Deng, X.; Duan, Z.; Fu, R.; Liang, L.; Fan, D. Ginsenoside Rk1 induces apoptosis and downregulates the expression of PD-L1 by targeting the NF-kappaB pathway in lung adenocarcinoma. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 456–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.Y.; Jiang, X.M.; Xu, Y.L.; Yuan, L.W.; Chen, Y.C.; Cui, G.; Huang, R.Y.; Liu, B.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; et al. Platycodin D triggers the extracellular release of programed death Ligand-1 in lung cancer cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 131, 110537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, W.; Gong, C.; Yan, X.; Si, G.; Fang, C.; Wang, L.; Zhu, X.; Xu, Z.; Yao, C.; Zhu, S. Targeting CD155 by rediocide-A overcomes tumour immuno-resistance to natural killer cells. Pharm. Biol. 2021, 59, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, S.; Dong, W.; Chu, Q.; Meng, J.; Yang, H.; Du, Y.; Sun, Y.U.; Hoffman, R.M. Traditional Chinese Medicine Brucea Javanica Oil Enhances the Efficacy of Anlotinib in a Mouse Model of Liver-Metastasis of Small-cell Lung Cancer. In Vivo 2021, 35, 1437–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damjanovic, A.; Kolundzija, B.; Matic, I.Z.; Krivokuca, A.; Zdunic, G.; Savikin, K.; Jankovic, R.; Stankovic, J.A.; Stanojkovic, T.P. Mahonia aquifolium Extracts Promote Doxorubicin Effects against Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells In Vitro. Molecules 2020, 25, 5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Chen, C.; Saud, S.M.; Geng, L.; Zhang, G.; Liu, R.; Hua, B. Fei-Liu-Ping ointment inhibits lung cancer growth and invasion by suppressing tumor inflammatory microenvironment. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, R.; Zheng, H.; Li, W.; Guo, Q.; He, S.; Hirasaki, Y.; Hou, W.; Hua, B.; Li, C.; Bao, Y.; et al. Anti-tumor enhancement of Fei-Liu-Ping ointment in combination with celecoxib via cyclooxygenase-2-mediated lung metastatic inflammatory microenvironment in Lewis lung carcinoma xenograft mouse model. J. Transl. Med. 2015, 13, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lin, Y.S.; Hsieh, C.Y.; Kuo, T.T.; Lin, C.C.; Lin, C.Y.; Sher, Y.P. Resveratrol-mediated ADAM9 degradation decreases cancer progression and provides synergistic effects in combination with chemotherapy. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2020, 10, 3828–3837. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Wu, T.C.; Hong, D.M.; Hu, Y.; Fan, T.; Guo, W.J.; Xu, Q. Carnosic acid enhances the anti-lung cancer effect of cisplatin by inhibiting myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2018, 16, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, W.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, X.; Tan, M. Ginsenoside Rh2 Improves the Cisplatin Anti-tumor Effect in Lung Adenocarcinoma A549 Cells via Superoxide and PD-L1. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2020, 20, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Bi, L.; Luo, H.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, F.; Wang, Y.; Wei, G.; Chen, W. Water extract of ginseng and astragalus regulates macrophage polarization and synergistically enhances DDP’s anticancer effect. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 232, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 2000, 100, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pandya, N.M.; Dhalla, N.S.; Santani, D.D. Angiogenesis--A new target for future therapy. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2006, 44, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, M.; Gordon, E.; Claesson-Welsh, L. Mechanisms and regulation of endothelial VEGF receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torok, S.; Rezeli, M.; Kelemen, O.; Vegvari, A.; Watanabe, K.; Sugihara, Y.; Tisza, A.; Marton, T.; Kovacs, I.; Tovari, J.; et al. Limited Tumor Tissue Drug Penetration Contributes to Primary Resistance against Angiogenesis Inhibitors. Theranostics 2017, 7, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zimna, A.; Kurpisz, M. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 in Physiological and Pathophysiological Angiogenesis: Applications and Therapies. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 549412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, P.; Weaver, V.M.; Werb, Z. The extracellular matrix: A dynamic niche in cancer progression. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 196, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kai, F.; Drain, A.P.; Weaver, V.M. The Extracellular Matrix Modulates the Metastatic Journey. Dev. Cell 2019, 49, 332–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Chang, K.W.; Yang, H.Y.; Lin, P.W.; Chen, S.U.; Huang, Y.L. MT1-MMP regulates MMP-2 expression and angiogenesis-related functions in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 437, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) as a Cancer Biomarker and MMP-9 Biosensors: Recent Advances. Sensors 2018, 18, 3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hewlings, S.J.; Kalman, D.S. Curcumin: A Review of Its Effects on Human Health. Foods 2017, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulzmaier, F.J.; Jean, C.; Schlaepfer, D.D. FAK in cancer: Mechanistic findings and clinical applications. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, L.C.; Shibu, M.A.; Liu, C.J.; Han, C.K.; Ju, D.T.; Chen, P.Y.; Viswanadha, V.P.; Lai, C.H.; Kuo, W.W.; Huang, C.Y. ERK1/2 mediates the lipopolysaccharide-induced upregulation of FGF-2, uPA, MMP-2, MMP-9 and cellular migration in cardiac fibroblasts. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2019, 306, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishikawa, M.; Hashida, M. Inhibition of tumour metastasis by targeted delivery of antioxidant enzymes. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2006, 3, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Majumdar, D.K.; Rehan, H.M. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory potential of fixed oil of Ocimum sanctum (Holybasil) and its possible mechanism of action. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1996, 54, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Luo, X.; Sumithran, E.; Pua, V.S.; Barnetson, R.S.; Halliday, G.M.; Khachigian, L.M. Squamous cell carcinoma growth in mice and in culture is regulated by c-Jun and its control of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 expression. Oncogene 2006, 25, 7260–7266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vayalil, P.K.; Katiyar, S.K. Treatment of epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits matrix metalloproteinases-2 and -9 via inhibition of activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases, c-jun and NF-kappaB in human prostate carcinoma DU-145 cells. Prostate 2004, 59, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, L.W.; Leung, P.C.; Wong, A.S. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone promotes ovarian cancer cell invasiveness through c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase-mediated activation of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and MMP-9. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 10902–10910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shieh, J.M.; Chiang, T.A.; Chang, W.T.; Chao, C.H.; Lee, Y.C.; Huang, G.Y.; Shih, Y.X.; Shih, Y.W. Plumbagin inhibits TPA-induced MMP-2 and u-PA expressions by reducing binding activities of NF-kappaB and AP-1 via ERK signaling pathway in A549 human lung cancer cells. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2010, 335, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesely, M.D.; Kershaw, M.H.; Schreiber, R.D.; Smyth, M.J. Natural innate and adaptive immunity to cancer. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 29, 235–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Childs, R.W.; Carlsten, M. Therapeutic approaches to enhance natural killer cell cytotoxicity against cancer: The force awakens. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chioda, M.; Peranzoni, E.; Desantis, G.; Papalini, F.; Falisi, E.; Solito, S.; Mandruzzato, S.; Bronte, V. Myeloid cell diversification and complexity: An old concept with new turns in oncology. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2011, 30, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabrilovich, D.I.; Nagaraj, S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Patel, S.; Tcyganov, E.; Gabrilovich, D.I. The Nature of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 2016, 37, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Groth, C.; Hu, X.; Weber, R.; Fleming, V.; Altevogt, P.; Utikal, J.; Umansky, V. Immunosuppression mediated by myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) during tumour progression. Br. J. Cancer 2019, 120, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Law, A.M.K.; Valdes-Mora, F.; Gallego-Ortega, D. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells as a Therapeutic Target for Cancer. Cells 2020, 9, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galiniak, S.; Aebisher, D.; Bartusik-Aebisher, D. Health benefits of resveratrol administration. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2019, 66, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bouillon, R.; Carmeliet, G.; Verlinden, L.; van Etten, E.; Verstuyf, A.; Luderer, H.F.; Lieben, L.; Mathieu, C.; Demay, M. Vitamin D and human health: Lessons from vitamin D receptor null mice. Endocr. Rev. 2008, 29, 726–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, P.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L. The structures and biological functions of polysaccharides from traditional Chinese herbs. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2019, 163, 423–444. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, J.; Liu, L.; Xu, Q.; Ren, J.; Xu, Z.; Dou, H.; Shen, S.; Hou, Y.; Mou, Y.; Wang, T. CARD9 prevents lung cancer development by suppressing the expansion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and IDO production. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 145, 2225–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiguro, S.; Upreti, D.; Robben, N.; Burghart, R.; Loyd, M.; Ogun, D.; Le, T.; Delzeit, J.; Nakashima, A.; Thakkar, R.; et al. Water extract from Euglena gracilis prevents lung carcinoma growth in mice by attenuation of the myeloid-derived cell population. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 127, 110166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapouri-Moghaddam, A.; Mohammadian, S.; Vazini, H.; Taghadosi, M.; Esmaeili, S.A.; Mardani, F.; Seifi, B.; Mohammadi, A.; Afshari, J.T.; Sahebkar, A. Macrophage plasticity, polarization, and function in health and disease. J. Cell Physiol. 2018, 233, 6425–6440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanmee, T.; Ontong, P.; Konno, K.; Itano, N. Tumor-associated macrophages as major players in the tumor microenvironment. Cancers 2014, 6, 1670–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Condeelis, J.; Pollard, J.W. Macrophages: Obligate partners for tumor cell migration, invasion, and metastasis. Cell 2006, 124, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wan, L.Q.; Tan, Y.; Jiang, M.; Hua, Q. The prognostic impact of traditional Chinese medicine monomers on tumor-associated macrophages in non-small cell lung cancer. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2019, 17, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, J.W. Tumour-educated macrophages promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S.; Mukherjee, P. MUC1: A multifaceted oncoprotein with a key role in cancer progression. Trends Mol. Med. 2014, 20, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ayob, A.Z.; Ramasamy, T.S. Cancer stem cells as key drivers of tumour progression. J. Biomed. Sci. 2018, 25, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Lin, J.; Xu, A.; Lou, J.; Qian, C.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Yu, W.; Tao, H. CCL2: An Important Mediator Between Tumor Cells and Host Cells in Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 722916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmall, A.; Al-Tamari, H.M.; Herold, S.; Kampschulte, M.; Weigert, A.; Wietelmann, A.; Vipotnik, N.; Grimminger, F.; Seeger, W.; Pullamsetti, S.S.; et al. Macrophage and cancer cell cross-talk via CCR2 and CX3CR1 is a fundamental mechanism driving lung cancer. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 191, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Wang, W.; Wang, S.; Yang, T.; Zhang, G.; Wang, D.; Ju, R.; Lu, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, L. Tumor microenvironment remodeling and tumor therapy based on M2-like tumor associated macrophage-targeting nano-complexes. Theranostics 2021, 11, 2892–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.B.; Andrade, P.B.; Valentao, P. Chemical Diversity and Biological Properties of Secondary Metabolites from Sea Hares of Aplysia Genus. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jain, P.; Jain, C.; Velcheti, V. Role of immune-checkpoint inhibitors in lung cancer. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2018, 12, 1753465817750075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iams, W.T.; Porter, J.; Horn, L. Immunotherapeutic approaches for small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonetti, A.; Wever, B.; Mazzaschi, G.; Assaraf, Y.G.; Rolfo, C.; Quaini, F.; Tiseo, M.; Giovannetti, E. Molecular basis and rationale for combining immune checkpoint inhibitors with chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Drug Resist. Updat. 2019, 46, 100644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y. Cancer immunotherapy: Harnessing the immune system to battle cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 3335–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Suresh, K.; Naidoo, J.; Lin, C.T.; Danoff, S. Immune Checkpoint Immunotherapy for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Benefits and Pulmonary Toxicities. Chest 2018, 154, 1416–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppenheim, J.J. IL-2: More than a T cell growth factor. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 1413–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, N.; Zhou, L.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, T.; Fang, Y.; Deng, J.; Gao, Y.; Liang, X.; et al. IL-2 regulates tumor-reactive CD8(+) T cell exhaustion by activating the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonangeli, F.; Natalini, A.; Garassino, M.C.; Sica, A.; Santoni, A.; Di Rosa, F. Regulation of PD-L1 Expression by NF-kappaB in Cancer. Front Immunol. 2020, 11, 584626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Huang, A.C.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, G.; Wu, M.; Xu, W.; Yu, Z.; Yang, J.; Wang, B.; Sun, H.; et al. Exosomal PD-L1 contributes to immunosuppression and is associated with anti-PD-1 response. Nature 2018, 560, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; You, X.; Han, S.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. CD155/TIGIT, a novel immune checkpoint in human cancers (Review). Oncol. Rep. 2021, 45, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Qi, J.; Chen, N.; Fu, W.; Zhou, B.; He, A. High expression of a disintegrin and metalloproteinase-9 predicts a shortened survival time in completely resected stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2013, 5, 1461–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhou, R.; Cho, W.C.S.; Ma, V.; Cheuk, W.; So, Y.K.; Wong, S.C.C.; Zhang, M.; Li, C.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, H.; et al. ADAM9 Mediates Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Progression via AKT/NF-kappaB Pathway. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzocca, A.; Coppari, R.; De Franco, R.; Cho, J.Y.; Libermann, T.A.; Pinzani, M.; Toker, A. A secreted form of ADAM9 promotes carcinoma invasion through tumor-stromal interactions. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 4728–4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, J.; Huang, Y.; Kumar, A.; Tan, A.; Jin, S.; Mozhi, A.; Liang, X.J. pH-sensitive nano-systems for drug delivery in cancer therapy. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014, 32, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, M.; Chen, G.; Qin, L.; Qu, C.; Dong, X.; Ni, J.; Yin, X. Metal Organic Frameworks as Drug Targeting Delivery Vehicles in the Treatment of Cancer. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, P.; Wang, X.; Liang, X.; Yang, J.; Zhang, C.; Kong, D.; Wang, W. Nano-, micro-, and macroscale drug delivery systems for cancer immunotherapy. Acta Biomater. 2019, 85, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriamornsak, P. Application of pectin in oral drug delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2011, 8, 1009–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Meng, Y.J.; Li, J.; Liu, J.P.; Liu, Z.Q.; Li, D.Q. A novel and simple oral colon-specific drug delivery system based on the pectin/modified nano-carbon sphere nanocomposite gel films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 157, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, T.; Liu, D.D.; Ning, H.M.; Dan, L.; Sun, J.Y.; Huang, X.J.; Dong, Y.; Geng, M.Y.; Yun, S.F.; Yan, J.; et al. Modified citrus pectin inhibited bladder tumor growth through downregulation of galectin-3. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2018, 39, 1885–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, S.L.; Mao, Y.Q.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Li, Z.M.; Kong, C.Y.; Chen, H.L.; Cai, P.R.; Han, B.; Ye, T.; Wang, L.S. Pectin supplement significantly enhanced the anti-PD-1 efficacy in tumor-bearing mice humanized with gut microbiota from patients with colorectal cancer. Theranostics 2021, 11, 4155–4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, D.; Shewale, R.; Patil, V.; Mali, D.; Gaikwad, U.; Jadhav, N. Enhancement in in vitro anti-angiogenesis activity and cytotoxicity in lung cancer cell by pectin-PVP based curcumin particulates. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 104, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Natural Products | Common Source | Cell Lines or Animal Models or Patients | Function or Molecular Mechanism | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Targeting angiogenesis | |||||

| 1 | Jolkinolide A (1) | Euphorbia fischeriana | A549, HUVEC; A549 cell xenograft mice | Inhibition of the Akt-STAT3-mTOR signaling pathway and reduction of VEGF protein expression; inhibition of HUVEC migration | [10] |

| 2 | Jolkinolide B (2) | ||||

| 3 | Parthenolide (3) | Tanacetum parthenium | A549, H526 | Inhibition of A549 and H526 cell proliferation in the presence and absence of nicotine; induction of apoptosis; inhibition of angiogenesis; down-regulation of Bcl-2 expression and up-regulation of E2F1, p53, GADD45, Bax, Bim, and caspase 3,7,8,9 expression | [11] |

| 4 | Galbanic acid (4) | Ferula assafoetida | LLC, HUVEC; LLC-bearing mice | Inhibition of VEGF-inducible HUVECs and LLC proliferation; tube formation, migration/invasion inhibition in HUVECs; decreased phosphorylation of p38MAPK, JNK and Akt, and decreased expression of VEGFR targeting eNOS; inhibition of tumor-induced angiogenesis and tumor growth in mice; reduction of CD34 and Ki67 | [12] |

| 5 | Salvicine (5) | Salvia prionitis | A549, HMEC | Inhibition of A549 cell viability; inhibition of the migration and tube formation of HMECs; reduced mRNA expression levels of bFGF; VEGF mRNA expression unchanged | [13] |

| 6 | Tanshinone IIA (6) | Salvia miltiorrhiza | A549 | Proliferation inhibition; apoptosis induction; cell cycle arrest at the S stage; downregulation of protein expression of VEGF and VEGFR2 | [14] |

| 7 | β-hydroxyisovalerylshikonin (7) | Lithospermum erythrorhizon | HUVEC, VPC; LLC xenograft mice | Inhibition of blood vessel formation by chicken chorioallantoic membrane assay; suppression of in vivo angiogenesis; suppression of VEGFR2 and Tie2; inhibition of HUVECs and VPC growth; suppression of MAPK and Sp1-dependent VEGFR2 and Tie2 mRNA expression | [15] |

| 8 | Isogambogenic acid (8) | Gamboge hanburyi | A549, HUVEC; transgenic FLK-1 promoter EGFP zebrafish; A549 xenograft mice | More effective for inhibiting HUVEC proliferation than A549; angiogenesis inhibition in zebrafish embryos; suppression of angiogenesis and tumor growth in mice; inhibition of vessel sprouting ex vivo; inhibition of VEGF-induced migration, invasion, and tube formation, morphological changes in HUVECs | [16] |

| 9 | Tubeimoside-1 (9) | Bolbostemma paniculatum | H460, A549, eEND2; H460 xenograft mice | Inhibition of tumor growth and vascularization; vascular sprouting; eEND2, H460, and A549 cell viability; eEND2 cell migration; VEGFR2 and Tie2 expression; and the Akt/mTOR pathway | [17] |

| 10 | Decursin (10) | Angelica gigas | HUVEC, LLC; LLC xenograft mice | Inhibition of VEGF-induced HUVEC proliferation, angiogenesis, and blood vessel formation; suppression of VEGF-induced phosphorylation of p42/44 ERK and JNK MAPK in endothelial cells and VEGF-induced MMP-2 activation; suppression of tumor growth and angiogenesis in nude mice | [18] |

| 11 | Decursinol angelate (11) | ||||

| 12 | Farnesiferol C (12) | Ferula assafoetida | HUVEC, LLC; LLC allograft tumor mice | Inhibition of VEGF-induced proliferation, migration, invasion, and MMP-2 secretion of HUVECs; inhibition of VEGF-induced vessel sprouting ex vivo; inhibition of tumor growth, angiogenesis, proliferation in vivo; inhibition of VEGF-induced phosphorylation of p125 FAK (pY861), Src (pY416), ERK1/2, p38MAPK, and JNK | [19] |

| 13 | Ergosterol (13) | Agaricus blazei | s180, LLC; s180 and LLC-bearing mice; mice inoculated with matrigel | Prevention of neovascularization induced by both LLC cells and matrigel; inhibition of tumor growth | [20] |

| 14 | Grape seed proanthocyanidins (GSP) | A549, H1299, H226, H460, H157, H1975, H1650, H3255, HCC827, BEAS-2B; A549 and H1299 xenograft mice | Inhibition of the proliferation of human lung cancer cells but not normal human bronchial epithelial cells; GSP-induced inhibition of proliferation is blocked by IGFBP-3 knockdown; inhibition of tumor growth and neovascularization; upregulation of IGFBP-3 protein levels in plasma and lung tumors; inhibition of VEGF expression | [21,22,23,24,25] | |

| 15 | Pomegranate fruit extract | B(a)P-induced lung tumorigenesis in A/J mouse | Inhibition of the activation of NF-κB, IKKα, PI3k and mTOR, and phosphorylation of IκBα, MAPKs, Akt and c-met; down-regulation of Ki-67, PCNA, CD31, VEGF, and iNOS expression | [26] | |

| 16 | Extracts of Astragali Mongolici and Rhizoma Curcumae | LLC-bearing mice | Decreases in tumor weight and tumor MVD; down-regulation of p38 MAPK, p-p38 MAPK, ERK1/2, p-ERK1/2, JNK, p-JNK, and VEGF expression | [27] | |

| 17 | Scutellaria barbata extract | CL1-5, HEL299, 293T, LL2, HMEC-1; LL2 lung metastatic mice | Decrease in the transcriptional activity of HIF-1α by inactivation of AKT; inhibition of VEGF expression in CL1-5 cells, migration and proliferation of HMEC-1 cells; inhibition of tumor growth | [28] | |

| 18 | Ginkgo biloba exocarp extracts | LLC; LLC transplanted tumor mice | Inhibition of LLC cell proliferation; downregulation of CD34, Wnt3α, β-catenin, p-AKT/AKT, VEGF, and VEGFR2 expression | [29] | |

| 19 | Green tea extract | NNK-induced lung tumorigenesis in mouse | Decreases in CD31, MVD and VEGF expression; apoptosis | [30] | |

| 20 | An-te-xiao capsule | Chinese medicine | A549, H460, H520, LLC, HUVEC; LLC xenograft mouse; H460 and H520 xenograft mice | No acute oral toxicity; prolongation of survival time; inhibition of tumor growth; decreases in MVD, CD31, and the blood vessel number; inhibition of Td-EC migration, invasion, and tube formation in the presence or absence of VEGF; inhibition of VEGF secretion and VEGFR2 phosphorylation | [31] |

| 21 | Erbanxiao solution | Chinese medicine | Patients with lung cancer | Inhibition of tumor angiogenesis by changing the levels of VEGF, bFGF, and TNF-α | [32] |

| 22 | Ka-mi-kae-kyuk-tang | Korean herbal cocktail | HUVEC, LLC; LLC-bearing mice; PC-3 xenograft mice | Suppression of bFGF stimulated endothelial membrane receptor-tyrosine kinase signaling to ERK1/2, cell motility, capillary differentiation, and to a less extent mitogenesis; inhibition of HIF1α and VEGF; suppression of tumor growth; | [33] |

| 23 | Qingzaojiufei decoction | Chinese medicine | LLC | Inhibition of LLC proliferation and growth; up-regulation of p53, and down-regulation of c-myc and Bcl-2; reducion of MMP-9, VEGF, VEGFR, p-ERK1/2 | [34] |

| 24 | Yiqichutan formula | Chinese medicine | A549, H460, H446; A549-bearing rats, H460-bearing rats, H446-bearing rats | Inhibition of tumor growth; reductions in CD31 expression and the number of blood vessels; decreases in VEGF, HIF-1, DLL4, and Notch-1 protein expression and VEGF mRNA expression | [35] |

| Targeting the ECM | |||||

| 25 | Curcumin (14) | Curcuma logna | A549; A549 xenograft mice | Attenuation of the GLUT1/MT1-MMP/MMP2 pathway | [36] |

| 26 | Honokiol (15) | Magnolia officinalis | H1299 | Disruption of HDAC6-mediated Hsp90/MMP-9 interaction; MMP-9 protein degradation; inhibition of migration, invasion, and MMP-9 proteolytic activity and expression; regulation of ubiquitin proteasome system | [37] |

| 27 | Theaflavin (16) | Black tea | LL2-Lu3 | Inhibition of cell invasion, MMP-2 and MMP-9 secretion, and type IV collagenases | [38] |

| 28 | Theaflavin digallate (17) | ||||

| 29 | EGCG (18) | Green tea | CL1-5, CL1-0 | Cell cycle G2/M arrest; inhibition of cell invasion and migration; repression of MMP-2 and -9 activities; reduction of nuclear translocation of NF-κB and Sp1; JNK signaling pathway | [39,40] |

| A549, HUVEC; A549 xenograft mice | Inhibition of nicotine-induced migration and invasion; down-regulation of HIF-1α, VEGF, COX-2, p-Akt, p-ERK, and vimentin protein levels; up-regulation of p53 and β-catenin protein levels; suppression of HIF-1α and VEGF protein expression | [41] | |||

| 30 | Steroidal saponins extracted from Paris polyphylla | A549 | Suppression of cell proliferation, adhesion, migration, and invasion; downregulation of MMP-2 and -9 protein levels; inhibition of MMP-2 and -9 activity | [42] | |

| 31 | Methanolic extract of Euchelus asper | A549; chick chorio-allantoic membrane model | Cell cycle subG1 phase arrest; reduction of A549 proliferation, MMP-2 and -9; decrease of the branching points of the 1st order blood vessels or capillaries of the chorio-allantoic membrane | [43] | |

| 32 | Phyllanthus urinaria extract | A549, LLC; LLC-bearing mice | Cytotoxicity; inhibition of invasion and migration; inhibition of u-PA, and MMP-2 and -9 activity; inhibition of TIMP-2 and PAI-1 protein expression; inhibition of transcriptional activity of MMP-2 promoter; inhibition of p-Akt, NF-κB, c-Jun, and c-Fos; decrease in lung metastases | [44] | |

| 33 | Rosa gallica petal extract | A549 | Downregulation of the PCNA, cyclin D1, and c-myc; suppression of cell migration and invasion; inhibition of the expression and activity of MMP-2 and -9; regulation of EGFR-MAPK and mTOR-Akt signaling pathways | [45] | |

| 34 | Viola Yedoensis extract | A549, LLC | Cytotoxicity; inhibition of cell invasiveness and migration; suppression of MMP-2, -9 and u-PA; decreases in TIMP-2 and TIMP-1 protein levels; increase in PAI-1 protein expression; decreasein NF-κB DNA binding activity | [46] | |

| 35 | Cinnamomum cassia extract | A549, H1299 | Cytotoxicity; inhibition of cell migration, invasiveness and motility; inhibition of MMP-2 u-PA, and RhoA protein levels; decrease of cell-matrix adhesion to gelatin and collagen; decrease of FAK and ERK1/2 phosphorylation; | [47] | |

| 36 | Duchesnea indica extracts | A549, H1299 | Inhibition of MMP-2 and u-PA activity; cell invasion and metastasis inhibition; downregulation of the expression of p-ERK, p-FAK Tyr397, p-paxillin Tyr118, c-Jun, c-Fos, and TGF-b1 induced-vimentin; inhibition of tumor growth | [48] | |

| 37 | Fructus phyllanthi tannin fraction | H1703, H460, A549, HT1080 | Cytotoxicity; inhibition of cell migration and invasion; down-regulation of p-ERK1/2, MMP-2 and -9 expression level, up-regulation of p-JNK expression; regulation of the MAPK pathway | [49] | |

| 38 | Butanol fraction extract of Psidium cattleianum leaf | H1299 | Suppression of activities, protein and mRNA expression levels of MMP-2 and -9; inhibition of adhesion, migration and invasion; downregulation of the mRNA level of uPAR; suppression of the ERK1/2 signaling pathway | [50] | |

| 39 | Terminalia catappa leaf extract | A549, LLC | Absence of cytotoxicity; inhibition of invasion, metastasis and motility; inhibition of u-PA, MMP-2 and -9 activity; inhibition of protein levels of TIMP-2 and PAI-1 | [51] | |

| 40 | Rhizoma Paridis saponins | LA795 xenograft mice | Inhibition of tumor growth; downregulation of mRNA expression of MMP-2 and -9 and ascendance of TIMP-2 | [52] | |

| 41 | Selaginella tamariscina extract | A549, LLC; LLC-bearing mice | Inhibition of invasion and motility; reduced activity of u-PA MMP-2 and -9; increase of protein levels of TIMP-2 and PAI-1 in A549 cells; decrease in lung metastases in mice | [53] | |

| 42 | Ethanol extract of Ocimum sanctum | LLC; LLC lung metastasis mouse model | Cytotoxicity; inhibition of cell adhesion and invasion; inhibition of nodules mediated by LLC cells; decrease in the activity of the enzymes SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px | [54] | |

| 43 | Rhubarb serum metabolites | A549; A549 lung metastatic mouse model | Suppression of the activity and expression level of MMP-2; inhibition of NF-κB/c-Jun pathway; inhibition of u-PA expression; inhibition of cell motility in vitro and lung metastasis in vivo | [55] | |

| 44 | Fuzheng Kang-Ai decoction | Chinese medicine | A549, PC9, H1650 | Suppression of cell proliferation; inhibition of cell migration and invasion; downregulation of MMP-9 activity and protein expression; downregulation of EMT related protein N-cadherin and vimentin | [56] |

| 45 | Yifei Tongluo | Chinese medicine | LLC-bearing mice | Inhibition of tumor growth; prolonged survival; fewer nodules on the lung surface; inhibition of MVD, CD34, VEGF, MMP-2, MMP-9, N-cadherin, and vimentin; increases in E-cadherin expression and NK cytotoxic activity; increased percentages of CD4+, CD8+ T, and NK cells; upregulation of Th1-type cytokines and levels of IFN-γ and IL-2 in the serum and reduction in IL-10 and TGF-β1; downregulation of PI3K/AKT, MAPK, and TGFβ/Smad2 pathways; upregulation of the JNK and p38 pathways | [57] |

| Targeting MDSCs | |||||

| 46 | Resveratrol (19) | Grape skin and seeds | LLC; LLC-bearing mice | Decrease in G-MDSC accumulation by triggering its apoptosis and decreasing recruitment; promotion of CD8+IFN-γ+ cell expansion; impairing the suppressive capability of G-MDSC on CD8+ T cells; G-MDSC differentiation into CD11c+orF4/80+ cells | [58] |

| 47 | Silymarin (20) | Silybum marianum | LLC-bearing mice | Inhibition of tumor growth; apoptosis; increases in the infiltration and function of CD8+ T cells; increases in IFN-γ and IL-2 levels, decrease in the IL-10 level | [59] |

| 48 | Vitamin D (21) | Sea fish, animal liver, etc. | COVID-19 patients | Beneficial effects come from reducing the macrophage and MDSC hyperinflammatory response | [60] |

| 49 | Polysaccharide from Ganoderma lucidum | LLC-bearing mice | Inhibition of tumor growth; reduction of MDSC accumulation in spleen and tumor tissue; increase in the percentage of CD4+, CD8+ T cells and IFN-γ and IL-12 production in the spleen; decreases in arginase activity and NO production; increase in IL-12 production in tumor tissue; regulation of the CARD9-NF-κB-IDO pathway in MDSCs | [61] | |

| 50 | Curdlan produced by Alcaligenes faecalis | LLC-bearing mice | Promotion of MDSC differentiation; impairment of the suppressive capability of MDSCs; inhibition of tumor progression by reducing MDSCs and enhancing the CTL and Th1 responses; | [62] | |

| 51 | Ze-Qi-Tang formula | Chinese medicine | LLC; orthotopic lung cancer mouse model | G-MDSC apoptosis through the STAT3/S100A9/Bcl-2/Caspase-3 signaling pathway; elimination of MDSCs and enrichment of antitumor T cells; inhibition of tumor growth; prolongation of survival | [63] |

| Targeting TAMs | |||||

| 52 | Pterostilbene (22) | Pterocarpus santalinus | A549, H441 | Decrease in the induction of stemness by M2-TAMs; prevention of M2-TAM polarization and decrease in side-population cells; suppression of the self-renewal ability in M2-TAMs-co-cultured lung cancer cells accompanied by down-regulation of MUC1, NF-κB, CD133, β-catenin, and Sox2 expression | [64] |

| 53 | Dihydroisotanshinone I (23) | Salvia miltiorrhiza | A549, H460 | Inhibition of cell motility and migration; blockage of the macrophage recruitment ability of lung cancer cells; inhibition of CCL2 secretion; blockage of p-STAT3 | [65] |

| 54 | Ginsenoside Rh2 (24) | Ginseng | A549, H1299 | Inhibition of cell proliferation and migration; decrease in the secretion and mRNA and protein levels of VEGF-C, MMP-2, and -9; decreases in VEGF-C and CD206 expression by tumor tissues | [66] |

| 55 | Sea fare hydrolysate | A549, HCC-366, RAW264.7, | Polarization of M1 macrophages in RAW264.7 cells; reduction of IL-4-induced M2 polarization in mouse peritoneal macrophages with reductions in the M2 markers Arg-1 and Ym-1; suppression of M2 macrophage polarization in human TAMs with reductions in the M2 markers CCL18, CD206, CD209, fibronectin-1, and IL-10 and increases in the M1 markers IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α; reductions in the activity of STAT3 and p38 in TAMs; cytotoxicity and G2/M arrest | [67] | |

| 56 | Yu-Ping-Feng | Chinese medicine | orthotopic lung tumor-bearing mice | Survival prolongation; increases in the CD4+ T Cell and M1 macrophage populations; cytotoxicity of CD4+ T cells; enhancement of the Th1 immunity response; STAT1 activation in M1 macrophages | [68] |

| 57 | Bu-Fei- Decoction | Chinese medicine | A549, H1975; A549 and H1975 xenograft mice | Suppression of cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in TAM conditioned medium; reduced expression of IL-10 and PD-L1; suppression of A549 and H1975 tumor growth, and PD-L1, IL-10 and CD206 protein expression in xenograft mice | [69] |

| Targeting immune checkpoint | |||||

| 58 | Green tea extract and EGCG | A549, Lu99; NNK-induced lung tumor mice | Downregulation of IFN-γ-induced PD-L1 protein; inhibition of STAT1 and Akt phosphorylation; inhibition of the IFNR/JAK2/STAT1 and EGFR/Akt signaling pathway; reduction of PD-L1-positive cells and inhibition of tumor growth in mice | [70] | |

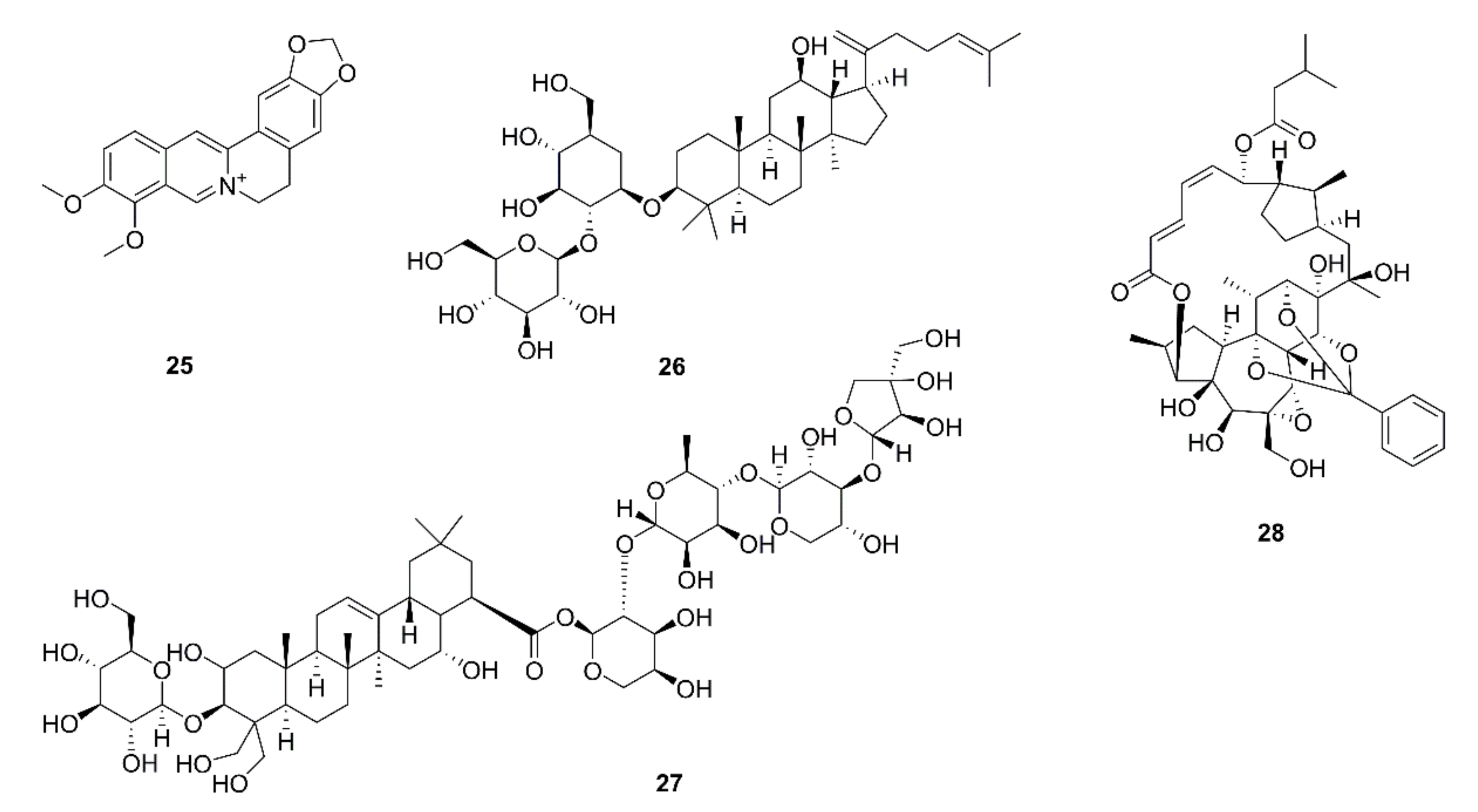

| 59 | Berberine (25) | Coptis chinensis | A549, H157, H358, H460, H1299, H1975, LLC, Jurkat; Lewis tumor xenograft mice | Negative regulator of PD-L1; decrease in PD-L1 expression; recovery of the sensitivity of cancer cells to T-cell killing; suppression of xenograft tumor growth; tumor-infiltrating T-cell activation; PD-L1 destabilization by binding to and inhibition of CSN5 activity; inhibition of CSN5 activity by directly binding to CSN5 at Glu76 | [71] |

| 60 | Ginsenoside Rk1 (26) | Ginseng | A549, PC9; A549 xenograft mice | Inhibition of cell proliferation and tumor growth; cell cycle arrest in the G1 phase; apoptosis via the NF-κB signaling pathway; downregulation of PD-L1 and NF-κB expression | [72] |

| 61 | Platycodin D (27) | Platycodon grandifloras | H1975, H358 | Decrease in the PD-L1 protein level; increase in IL-2 secretion; extracellular release of PD-L1 independent of the hemolytic mechanism | [73] |

| 62 | Rediocide A (28) | Trigonostemon rediocides | A549, H1299 | Blockage of cell immuno-resistance; increase in granzyme B release and IFN-γ secretion; down-regulation of CD155 expression | [74] |

| Natural Products | Combined Clinical Drugs | Cell Lines or Animal Models | Function or Molecular Mechanism | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brucea Javanica oil | Anlotinib | H446; H460 liver-metastasis mouse model | Enhancement of anlotinib efficacy against liver metastasis from SCLC; reduction of anlotinib-induced weight loss in mice; enhancement of the anti-angiogenic effect (inhibition of tumor microvessels growth) of amlotinib | [75] |

| Mahonia aquifolium extract | Doxorubicin | A549 | Increased cytotoxicity; cell cycle arrest in the subG1 phase; pronounced DOX retention; lower migratory ability and colony formation potential; decrease in MMP-9 expression | [76] |

| Fei-Liu-Ping ointment | Cyclophosphamide | A549, THP-1; LLC xenograft mice | Enhancement of tumor growth inhibition; down-regulation of the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β levels; increase in E-cadherin expression and decrease in N-cadherin and MMP-9, expression; inhibition of cell proliferation and invasion; inhibition of NF-κB activity, expression, and nuclear translocation | [77] |

| Celecoxib | LL/2-luc-M38; LLC xenograft mice | Enhancement of tumor growth inhibition; inhibition of Cox-2, mPGES-1, VEGF, PDGFRβ, MMP-2, and -9 expression; down-regulation of E-cadherin expression, upregulation of N-cadherin and Vimentin expression | [78] | |

| Resveratrol | Dasatinib, 5-fluorouridine | A549, Bm7 | Inhibition of cell migration; ADAM9 degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway; synergistic anticancer effects to inhibit cell proliferation | [79] |

| Carnosic acid | Cisplatin | LLC-bearing mice | Enhancement of tumor growth suppression and apoptosis; reduction of side effects (body weight loss) of cisplatin; promotion of CD8+ T cells-mediated antitumor immune response; function and accumulation decrease of MDSCs; downregulation of CD11b+ Gr1+ MDSCs, Arg-1, iNOS-2, and MMP-9 levels | [80] |

| Ginsenoside Rh2 | Cisplatin | A549, H1299 | Enhancement of cisplatin-induced cell apoptosis by repressing autophagy; scavenging of cisplatin-induced superoxide autophagy generation; inhibition of cisplatin-induced EGFR-PI3K-AKT pathway activation; inhibition of the cisplatin-induced PD-L1 expression | [81] |

| Water extract of ginseng | Cisplatin | A549, THP-1; LLC-bearing mice | Increase in the expression of the M1 macrophage marker iNOS, decrease in the expression of the M2 marker Arg-1; regulation of TAMs polarization; reductions in tumor growth and cisplatin-induced immunosuppression | [82] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Li, N.; Wang, T.-M.; Di, L. Natural Products with Activity against Lung Cancer: A Review Focusing on the Tumor Microenvironment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10827. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms221910827

Yang Y, Li N, Wang T-M, Di L. Natural Products with Activity against Lung Cancer: A Review Focusing on the Tumor Microenvironment. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(19):10827. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms221910827

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yue, Ning Li, Tian-Ming Wang, and Lei Di. 2021. "Natural Products with Activity against Lung Cancer: A Review Focusing on the Tumor Microenvironment" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 19: 10827. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms221910827