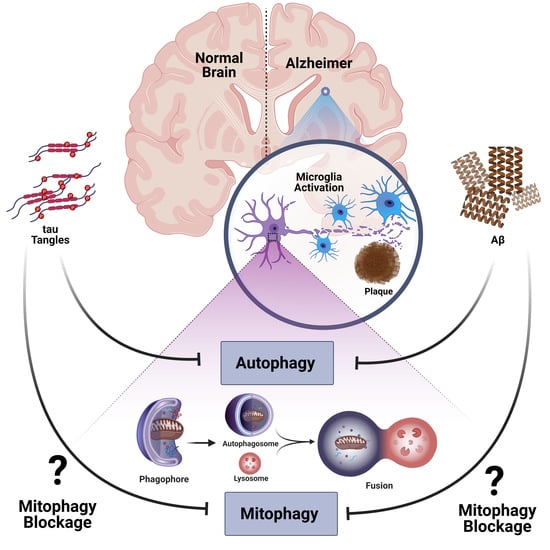

Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis: Role of Autophagy and Mitophagy Focusing in Microglia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Alzheimer’s Disease; A Global Health Crisis

3. Autophagy and AD

3.1. Autophagy

3.2. Dysregulation of Autophagy in AD

4. Mitophagy and AD

4.1. Mitophagy

4.2. Dysfunction of Mitochondria in AD

4.3. Dysfunction of Mitophagy in AD

5. Microglia, Neuroinflammation, and AD

5.1. Neuroinflammation in AD

5.2. Microglia

5.3. Over-Activation of Microglia in AD

5.3.1. Complement Receptors

5.3.2. Fc Receptors

5.3.3. Scavenger Receptors

5.3.4. Receptor for Advanced Glycation Endproducts (RAGE)

5.3.5. Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells 2 (TREM2)

5.3.6. CD33

5.3.7. Toll-like Receptors (TLRs)

5.4. Increased Levels of Proinflammatory Mediators in AD

5.4.1. Apolipoprotein E (APOE4)

5.4.2. Chemokines

5.4.3. High Mobility Group Box 1 (HMGB1)

5.4.4. S100 Proteins

6. Autophagy and Neuroinflammation in AD

6.1. Role of Impaired Autophagy in Neuroinflammation

6.2. Role of Neuroinflammation in Impairment of Autophagy

7. Mitophagy and Neuroinflammation in AD

7.1. Role of Impaired Mitophagy in Inflammation

7.2. Mitophagy and Microglia in AD

8. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Aβ | amyloid β |

| ADL | activities of daily living |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| APP | amyloid precursor protein |

| APOE | apolipoprotein E |

| BACE1 | β-secretase |

| BBB | blood–brain barrier |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| CR | complement receptors |

| CX3CR1 | chemokine receptor1 |

| CX3CL1 | chemokine ligand1 |

| Drp1 | dynamin-related protein1 |

| FcRs | Fc receptors |

| GDP | gross domestic product |

| IFNγ | interferon gamma |

| IL | interleukin |

| KDHC | α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex |

| LEARn | Latent Early- life Associated Regulation |

| MA-5 | mitochonic acid 5 |

| Mfn | mitofusion |

| MIP | macrophage inflammatory protein |

| MMP | mitochondrial membrane potential |

| mPTP | mitochondrial permeability transition pore |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa B |

| NFTs | neurofibrillary tangles |

| NLRP3 | NLR family pyrin domain, containing 3 |

| NLR | nucleotide-binding domain leucine-rich repeat |

| NMDARs | N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors |

| Opa1 | optic dominant atrophy1 |

| OXPHOS | oxidative phosphorylation |

| PDHC | pyruvate dehydrogenase complex |

| PD | Parkinson disease |

| PHF | paired helical filament |

| p-tau | phospho tau |

| PSEN | presenilin |

| RAGE | receptor for advanced glycation end products |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SCARA-1 | scavenger receptor A-1 |

| SRs | scavenger receptors |

| TCA | tricarboxylic acid cycle |

| TLRs | toll-like receptors |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-α |

| TREM2 | triggering receptor expressed in myeloid cells 2 |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Liu, P.-P.; Xie, Y.; Meng, X.-Y.; Kang, J.-S. History and progress of hypotheses and clinical trials for Alzheimer’s disease. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2019, 4, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, M. Paired helical filaments in electron microscopy of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 1963, 197, 192–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, R.D. The fine structure of neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1963, 22, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Glabe, C.C. Amyloid accumulation and pathogensis of Alzheimer’s disease: Significance of monomeric, oligomeric and fibrillar Abeta. Sub-Cell. Biochem. 2005, 38, 167–177. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, J.; Selkoe, D.J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: Progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002, 297, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yiannopoulou, K.G.; Anastasiou, A.I.; Zachariou, V.; Pelidou, S.H. Reasons for Failed Trials of Disease-Modifying Treatments for Alzheimer Disease and Their Contribution in Recent Research. Biomedicines 2019, 7, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hickman, S.; Izzy, S.; Sen, P.; Morsett, L.; El Khoury, J. Microglia in neurodegeneration. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 1359–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.W.; Zong, Y.; Cao, X.P.; Tan, L.; Tan, L. Microglial priming in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018, 6, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keren-Shaul, H.; Spinrad, A.; Weiner, A.; Matcovitch-Natan, O.; Dvir-Szternfeld, R.; Ulland, T.K.; David, E.; Baruch, K.; Lara-Astaiso, D.; Toth, B.; et al. A Unique Microglia Type Associated with Restricting Development of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell 2017, 169, 1276–1290.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavami, S.; Shojaei, S.; Yeganeh, B.; Ande, S.R.; Jangamreddy, J.R.; Mehrpour, M.; Christoffersson, J.; Chaabane, W.; Moghadam, A.R.; Kashani, H.H.; et al. Autophagy and apoptosis dysfunction in neurodegenerative disorders. Prog. Neurobiol. 2014, 112, 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wells, C.E. Dementia: Definition and description. Contemp. Neurol. Ser. 1977, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2015 WAsR. The Global Impact of Dementia: An analysis of Prevalence, Incidence, Cost and Trends. Alzheimer’s Disease International 2015. Available online: https://www.dementiastatistics.org/statistics/global-prevalence/ (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Prince, M.; Wimo, A.; Guerchet, M.; Ali, G.C.; Wu, Y.T.; Prina, M. World Alzheimer Report 2015: The Global Impact of Dementia: An Analysis of Prevalence, Incidence, Cost and Trends; Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI): London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Dementia Fact Sheet 2019. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs362/en/ (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Dementia. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Wimo, A.; Jonsson, L.; Bond, J.; Prince, M.; Winblad, B. Alzheimer Disease I. The worldwide economic impact of dementia 2010. Alzheimer’s Dement. J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2013, 9, 1–11.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam Vandongen, S.C. WA Reports; Western Australia Corporate Reports and Publications: Lawbook Co., Australia, 2011. Available online: https://legal.thomsonreuters.com.au/wa-reports/productdetail/110784 (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Adlimoghaddam, A.; Roy, B.; Albensi, B.C. Future Trends and the Economic Burden of Dementia in Manitoba: Comparison with the Rest of Canada and the World. Neuroepidemiology 2018, 51, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chappell, N.L.; Hollander, M.J. An evidence-based policy prescription for an aging population. Healthcarepapers 2011, 11, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fratiglioni, L.; De Ronchi, D.; Aguero-Torres, H. Worldwide prevalence and incidence of dementia. Drugs Aging 1999, 15, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fratiglioni, L.; Launer, L.J.; Andersen, K.; Breteler, M.M.; Copeland, J.R.; Dartigues, J.F.; Lobo, A.; Martinez-Lage, J.; Soininen, H.; Hofman, A. Incidence of dementia and major subtypes in Europe: A collaborative study of population-based cohorts. Neurologic Diseases in the Elderly Research Group. Neurology 2000, 54 (Suppl. 5), S10–S15. [Google Scholar]

- Aarsland, D.; Rongve, A.; Nore, S.P.; Skogseth, R.; Skulstad, S.; Ehrt, U.; Hoprekstad, D.; Ballard, C. Frequency and case identification of dementia with Lewy bodies using the revised consensus criteria. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2008, 26, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Disease Burden and Mortality Estimates. Available online: https://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates/en/ (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Cummings, J.L. Treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: Current and future therapeutic approaches. Rev. Neurol. Dis. 2004, 1, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, J.L. Alzheimer’s disease. New Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adlimoghaddam, A.; Neuendorff, M.; Roy, B.; Albensi, B.C. A review of clinical treatment considerations of donepezil in severe Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2018, 24, 876–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braak, H.; Braak, E. Frequency of stages of Alzheimer-related lesions in different age categories. Neurobiol. Aging. 1997, 18, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, G.W.; Rabins, P.V.; Barry, P.P.; Buckholtz, N.S.; DeKosky, S.T.; Ferris, S.H.; Finkel, S.I.; Gwyther, L.P.; Khachaturian, Z.S.; Lebowitz, B.D.; et al. Diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer disease and related disorders. Consensus statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, the Alzheimer’s Association, and the American Geriatrics Society. JAMA 1997, 278, 1363–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meek, P.D.; McKeithan, K.; Schumock, G.T. Economic considerations in Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacotherapy 1998, 18 (2 Pt 2), 68–73; discussion 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, O.L.; Becker, J.T.; Sweet, R.A.; Klunk, W.; Kaufer, D.I.; Saxton, J.; Habeych, M.; DeKosky, S.T. Psychiatric symptoms vary with the severity of dementia in probable Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2003, 15, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Flier, W.M.; Scheltens, P. Epidemiology and risk factors of dementia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2005, 76 (Suppl. 5), v2–v7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reitz, C.; Brayne, C.; Mayeux, R. Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2011, 7, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Group CSoHaAW. The Canadian Study of Health and Aging: Risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease in Canada. Neurology 1994, 44, 2073–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, J.H.R.; Rockwood, K. The Canadian Study of Health and Aging: Risk factors for vascular dementia. Stroke 1997, 28, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert, R.; Lindsay, J.; Verreault, R.; Rockwood, K.; Hill, G.; Dubois, M.F. Vascular dementia: Incidence and risk factors in the Canadian study of health and aging. Stroke 2000, 31, 1487–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekris, L.M.; Yu, C.-E.; Bird, T.D.; Tsuang, D.W. Genetics of Alzheimer disease. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2010, 23, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferri, C.P.; Prince, M.; Brayne, C.; Brodaty, H.; Fratiglioni, L.; Ganguli, M.; Hall, K.; Hasegawa, K.; Hendrie, H.; Huang, Y.; et al. Global prevalence of dementia: A Delphi consensus study. Lancet 2005, 366, 2112–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donix, M.; Ercoli, L.M.; Siddarth, P.; Brown, J.A.; Martin-Harris, L.; Burggren, A.C.; Miller, K.J.; Small, G.W.; Bookheimer, S.Y. Influence of Alzheimer disease family history and genetic risk on cognitive performance in healthy middle-aged and older people. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Off. J. Am. Assoc. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2012, 20, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pizzonia, J.H.; Ransom, B.R.; Pappas, C.A. Characterization of Na+/H+ exchange activity in cultured rat hippocampal astrocytes. J. Neurosci. Res. 1996, 44, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiraboschi, P.; Hansen, L.A.; Masliah, E.; Alford, M.; Thal, L.J.; Corey-Bloom, J. Impact of APOE genotype on neuropathologic and neurochemical markers of Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2004, 62, 1977–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmechel, D.E.; Saunders, A.M.; Strittmatter, W.J.; Crain, B.J.; Hulette, C.M.; Joo, S.H.; Pericak-Vance, M.A.; Goldgaber, D.; Roses, A.D. Increased amyloid beta-peptide deposition in cerebral cortex as a consequence of apolipoprotein E genotype in late-onset Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 9649–9653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zheng, H.; Cheng, B.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.W. TREM2 in Alzheimer’s Disease: Microglial Survival and Energy Metabolism. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Podcasy, J.L.; Epperson, C.N. Considering sex and gender in Alzheimer disease and other dementias. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 18, 437–446. [Google Scholar]

- Riggs, B.L.; Khosla, S.; Melton, L.J., 3rd. A unitary model for involutional osteoporosis: Estrogen deficiency causes both type I and type II osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and contributes to bone loss in aging men. J. Bone Miner. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res. 1998, 13, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Pozo, A.; Frosch, M.P.; Masliah, E.; Hyman, B.T. Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2011, 1, a006189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, B.T. The neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Clinical-pathological studies. Neurobiol. Aging 1997, 18, S27–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, V.W.; Mattson, M.P.; Wong, P.C.; Gleichmann, M. An overview of APP processing enzymes and products. Neuromolecular Med. 2010, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jack, C.R., Jr.; Knopman, D.S.; Jagust, W.J.; Shaw, L.M.; Aisen, P.S.; Weiner, M.W.; Petersen, R.C.; Trojanowski, J.Q. Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s pathological cascade. Lancet Neurol. 2010, 9, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barbier, P.; Zejneli, O.; Martinho, M.; Lasorsa, A.; Belle, V.; Smet-Nocca, C.; Tsvetkov, P.O.; Devred, F.; Landrieu, I. Role of Tau as a Microtubule-Associated Protein: Structural and Functional Aspects. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Iqbal, K.; Liu, F.; Gong, C.X.; Grundke-Iqbal, I. Tau in Alzheimer disease and related tauopathies. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2010, 7, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braak, H.; Braak, E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991, 82, 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, J.C. Early-stage and preclinical Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2005, 19, 163–165. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, S.; Shrestha, Y.; Jayatunga, D.P.W.; Rea, S.; Martins, R.; Bharadwaj, P. Activate or Inhibit? Implications of Autophagy Modulation as a Therapeutic Strategy for Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaei, S.; Suresh, M.; Klionsky, D.J.; Labouta, H.I.; Ghavami, S. Autophagy and SARS-CoV-2 infection: Apossible smart targeting of the autophagy pathway. Virulence 2020, 11, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaei, S.; Koleini, N.; Samiei, E.; Aghaei, M.; Cole, L.K.; Alizadeh, J.; Islam, M.I.; Vosoughi, A.R.; Albokashy, M.; Butterfield, Y.; et al. Simvastatin increases temozolomide-induced cell death by targeting the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 1005–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, J.; Shojaei, S.; Sepanjnia, A.; Hashemi, M.; Eftekharpour, E.; Ghavami, S. Simultaneous Detection of Autophagy and Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition in the Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1854, 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.Y.; Yan, J.; Zukin, R.S. Autophagy and synaptic plasticity: Epigenetic regulation. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2019, 59, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Fleming, A.; Ricketts, T.; Pavel, M.; Virgin, H.; Menzies, F.M.; Rubinsztein, D.C. Autophagy regulates Notch degradation and modulates stem cell development and neurogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zeng, Q.; Siu, W.; Li, L.; Jin, Y.; Liang, S.; Cao, M.; Ma, M.; Wu, Z. Autophagy in Alzheimer’s disease and promising modulatory effects of herbal medicine. Exp. Gerontol. 2019, 119, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.S.; Mamun, A.A.; Labu, Z.K.; Hidalgo-Lanussa, O.; Barreto, G.E.; Ashraf, G.M. Autophagic dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: Cellular and molecular mechanistic approaches to halt Alzheimer’s pathogenesis. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 8094–8112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavami, S.; Gupta, S.; Ambrose, E.; Hnatowich, M.; Freed, D.H.; Dixon, I.M. Autophagy and heart disease: Implications for cardiac ischemia-reperfusion damage. Curr. Mol. Med. 2014, 14, 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samiei, E.; Seyfoori, A.; Toyota, B.; Ghavami, S.; Akbari, M. Investigating Programmed Cell Death and Tumor Invasion in a Three-Dimensional (3D) Microfluidic Model of Glioblastoma. Int. J. Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehdizadeh, M.; Ashtari, N.; Jiao, X.; Rahimi Balaei, M.; Marzban, A.; Qiyami-Hour, F.; Kong, J.; Ghavami, S.; Marzban, H. Alteration of the Dopamine Receptors’ Expression in the Cerebellum of the Lysosomal Acid Phosphatase 2 Mutant (Naked-Ataxia (NAX)) Mouse. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastghaib, S.; Shojaei, S.; Mostafavi-Pour, Z.; Sharma, P.; Patterson, J.B.; Samali, A.; Mokarram, P.; Ghavami, S. Simvastatin Induces Unfolded Protein Response and Enhances Temozolomide-Induced Cell Death in Glioblastoma Cells. Cells 2020, 9, 2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaffagnini, G.; Martens, S. Mechanisms of Selective Autophagy. J. Mol Biol. 2016, 428 (9 Pt A), 1714–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sainani, S.R.; Pansare, P.A.; Rode, K.; Bhalchim, V.; Doke, R.; Desai, S. Emendation of autophagic dysfuction in neurological disorders: A potential therapeutic target. Int. J. Neurosci. 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Rosa, S.C.; Martens, M.D.; Field, J.T.; Nguyen, L.; Kereliuk, S.M.; Hai, Y.; Chapman, D.; Diehl-Jones, W.; Aliani, M.; West, A.R.; et al. BNIP3L/Nix-induced mitochondrial fission, mitophagy, and impaired myocyte glucose uptake are abrogated by PRKA/PKA phosphorylation. Autophagy 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlinden, K.D.; Kota, A.; Haghi, M.; Ghavami, S.; Sharma, P. Pharmacologic Inhibition of Vacuolar H(+)ATPase Attenuates Features of Severe Asthma in Mice. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2020, 62, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Klionsky, D.J. Mammalian autophagy: Core molecular machinery and signaling regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2010, 22, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tyler, J.K.; Johnson, J.E. The role of autophagy in the regulation of yeast life span. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2018, 1418, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, K.; Kubota, Y.; Sekito, T.; Ohsumi, Y. Hierarchy of Atg proteins in pre-autophagosomal structure organization. Genes Cells. 2007, 12, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iranpour, M.; Moghadam, A.R.; Yazdi, M.; Ande, S.R.; Alizadeh, J.; Wiechec, E.; Lindsay, R.; Drebot, M.; Coombs, K.M.; Ghavami, S. Apoptosis, autophagy and unfolded protein response pathways in Arbovirus replication and pathogenesis. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2016, 18, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Yokom, A.L.; Wang, C.; Young, L.N.; Youle, R.J.; Hurley, J.H. ULK complex organization in autophagy by a C-shaped FIP200 N-terminal domain dimer. J. Cell Biol. 2020, 219. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, R.C.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, H.; Park, H.W.; Chang, Y.Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Neufeld, T.P.; Dillin, A.; Guan, K.L. ULK1 induces autophagy by phosphorylating Beclin-1 and activating VPS34 lipid kinase. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harada, K.; Kotani, T.; Kirisako, H.; Sakoh-Nakatogawa, M.; Oikawa, Y.; Kimura, Y.; Hirano, H.; Yamamoto, H.; Ohsumi, Y.; Nakatogawa, H. Two distinct mechanisms target the autophagy-related E3 complex to the pre-autophagosomal structure. Elife 2019, 8, e43088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papinski, D.; Kraft, C. Regulation of autophagy by signaling through the Atg1/ULK1 complex. J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 428, 1725–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hosokawa, N.; Hara, T.; Kaizuka, T.; Kishi, C.; Takamura, A.; Miura, Y.; Iemura, S.; Natsume, T.; Takehana, K.; Yamada, N.; et al. Nutrient-dependent mTORC1 association with the ULK1-Atg13-FIP200 complex required for autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009, 20, 1981–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.; Kundu, M.; Viollet, B.; Guan, K.L. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 13, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, M.; Li, C.; Yang, S.; Xiao, Y.; Xiong, X.; Chen, W.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, Q.; Han, Y.; Sun, L. Mitochondria-Associated ER Membranes—The Origin Site of Autophagy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeganeh, B.; Jager, R.; Gorman, A.M.; Samali, A.; Ghavami, S. Induction of Autophagy: Role of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Unfolded Protein Response. In Autophagy: Cancer, Other Pathologies, Inflammation, Immunity, Infection, and Aging. 5; Hayat, M.A., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrbod, P.; Ande, S.R.; Alizadeh, J.; Rahimizadeh, S.; Shariati, A.; Malek, H.; Hashemi, M.; Glover, K.K.M.; Sher, A.A.; Coombs, K.M.; et al. The roles of apoptosis, autophagy and unfolded protein response in arbovirus, influenza virus, and HIV infections. Virulence 2019, 10, 376–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Otomo, C.; Metlagel, Z.; Takaesu, G.; Otomo, T. Structure of the human ATG12~ ATG5 conjugate required for LC3 lipidation in autophagy. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013, 20, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rai, S.; Arasteh, M.; Jefferson, M.; Pearson, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Bicsak, B.; Divekar, D.; Powell, P.P.; Naumann, R.; et al. The ATG5-binding and coiled coil domains of ATG16L1 maintain autophagy and tissue homeostasis in mice independently of the WD domain required for LC3-associated phagocytosis. Autophagy 2019, 15, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fang, E.F.; Hou, Y.; Palikaras, K.; Adriaanse, B.A.; Kerr, J.S.; Yang, B.; Lautrup, S.; Hasan-Olive, M.M.; Caponio, D.; Dan, X.; et al. Mitophagy inhibits amyloid-β and tau pathology and reverses cognitive deficits in models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emami, A.; Shojaei, S.; da Silva Rosa, S.C.; Aghaei, M.; Samiei, E.; Vosoughi, A.R.; Kalantari, F.; Kawalec, P.; Thliveris, J.; Sharma, P.; et al. Mechanisms of simvastatin myotoxicity: The role of autophagy flux inhibition. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 862, 172616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskelinen, E.L.; Saftig, P. Autophagy: A lysosomal degradation pathway with a central role in health and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1793, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lorzadeh, S.; Kohan, L.; Ghavami, S.; Azarpira, N. Autophagy and the Wnt Signaling Pathway: A Focus on Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell. Res. 2020, 118926. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon, R.A.; Wegiel, J.; Kumar, A.; Yu, W.H.; Peterhoff, C.; Cataldo, A.; Cuervo, A.M. Extensive involvement of autophagy in Alzheimer disease: An immuno-electron microscopy study. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2005, 64, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Terry, R.D.; Gonatas, N.K.; Weiss, M. The ultrastructure of the cerebral cortex in Alzheimer’s disease. Trans. Am. Neurol. Assoc. 1964, 89, 12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nixon, R.A.; Yang, D.S.; Lee, J.H. Neurodegenerative lysosomal disorders: A continuum from development to late age. Autophagy 2008, 4, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lajoie, P.; Guay, G.; Dennis, J.W.; Nabi, I.R. The lipid composition of autophagic vacuoles regulates expression of multilamellar bodies. J. Cell Sci. 2005, 118 (Pt 9), 1991–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nixon, R.A.; Yang, D.S. Autophagy failure in Alzheimer’s disease--locating the primary defect. Neurobiol. Dis. 2011, 43, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chong, C.M.; Ke, M.; Tan, Y.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, K.; Ai, N.; Ge, W.; Qin, D.; Lu, J.H.; Su, H. Presenilin 1 deficiency suppresses autophagy in human neural stem cells through reducing γ-secretase-independent ERK/CREB signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.S.; Stavrides, P.; Mohan, P.S.; Kaushik, S.; Kumar, A.; Ohno, M.; Schmidt, S.D.; Wesson, D.; Bandyopadhyay, U.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Reversal of autophagy dysfunction in the TgCRND8 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease ameliorates amyloid pathologies and memory deficits. Brain 2011, 134 (Pt 1), 258–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, M.; Waguri, S.; Chiba, T.; Murata, S.; Iwata, J.; Tanida, I.; Ueno, T.; Koike, M.; Uchiyama, Y.; Kominami, E.; et al. Loss of autophagy in the central nervous system causes neurodegeneration in mice. Nature 2006, 441, 880–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, T.; Nakamura, K.; Matsui, M.; Yamamoto, A.; Nakahara, Y.; Suzuki-Migishima, R.; Yokoyama, M.; Mishima, K.; Saito, I.; Okano, H.; et al. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature 2006, 441, 885–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Perlstein, E.O.; Imarisio, S.; Pineau, S.; Cordenier, A.; Maglathlin, R.L.; Webster, J.A.; Lewis, T.A.; O’Kane, C.J.; Schreiber, S.L.; et al. Small molecules enhance autophagy and reduce toxicity in Huntington’s disease models. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007, 3, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ravikumar, B.; Vacher, C.; Berger, Z.; Davies, J.E.; Luo, S.; Oroz, L.G.; Scaravilli, F.; Easton, D.F.; Duden, R.; O’Kane, C.J.; et al. Inhibition of mTOR induces autophagy and reduces toxicity of polyglutamine expansions in fly and mouse models of Huntington disease. Nat Genet. 2004, 36, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chauhan, R.; Chen, K.F.; Kent, B.A.; Crowther, D.C. Central and peripheral circadian clocks and their role in Alzheimer’s disease. Dis. Model. Mech. 2017, 10, 1187–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Polito, V.A.; Li, H.; Martini-Stoica, H.; Wang, B.; Yang, L.; Xu, Y.; Swartzlander, D.B.; Palmieri, M.; di Ronza, A.; Lee, V.M.; et al. Selective clearance of aberrant tau proteins and rescue of neurotoxicity by transcription factor EB. EMBO Mol. Med. 2014, 6, 1142–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.H.; Kumar, A.; Peterhoff, C.; Shapiro Kulnane, L.; Uchiyama, Y.; Lamb, B.T.; Cuervo, A.M.; Nixon, R.A. Autophagic vacuoles are enriched in amyloid precursor protein-secretase activities: Implications for beta-amyloid peptide over-production and localization in Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2004, 36, 2531–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boland, B.; Kumar, A.; Lee, S.; Platt, F.M.; Wegiel, J.; Yu, W.H.; Nixon, R.A. Autophagy induction and autophagosome clearance in neurons: Relationship to autophagic pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 6926–6937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yu, W.H.; Cuervo, A.M.; Kumar, A.; Peterhoff, C.M.; Schmidt, S.D.; Lee, J.H.; Mohan, P.S.; Mercken, M.; Farmery, M.R.; Tjernberg, L.O.; et al. Macroautophagy--a novel Beta-amyloid peptide-generating pathway activated in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Cell Biol. 2005, 171, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maejima, Y.; Isobe, M.; Sadoshima, J. Regulation of autophagy by Beclin 1 in the heart. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2016, 95, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pickford, F.; Masliah, E.; Britschgi, M.; Lucin, K.; Narasimhan, R.; Jaeger, P.A.; Small, S.; Spencer, B.; Rockenstein, E.; Levine, B.; et al. The autophagy-related protein beclin 1 shows reduced expression in early Alzheimer disease and regulates amyloid beta accumulation in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 2190–2199. [Google Scholar]

- Mattson, M.P.; Gleichmann, M.; Cheng, A. Mitochondria in neuroplasticity and neurological disorders. Neuron 2008, 60, 748–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stockburger, C.; Eckert, S.; Eckert, G.P.; Friedland, K.; Müller, W.E. Mitochondrial Function, Dynamics, and Permeability Transition: A Complex Love Triangle as A Possible Target for the Treatment of Brain Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 64, S455–S467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.; Lauretti, E.; Praticò, D. Caspase-3-dependent cleavage of Akt modulates tau phosphorylation via GSK3β kinase: Implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Psychiatry 2017, 22, 1002–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Means, J.C.; Gerdes, B.C.; Kaja, S.; Sumien, N.; Payne, A.J.; Stark, D.A.; Borden, P.K.; Price, J.L.; Koulen, P. Caspase-3-Dependent Proteolytic Cleavage of Tau Causes Neurofibrillary Tangles and Results in Cognitive Impairment During Normal Aging. Neurochem. Res. 2016, 41, 2278–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ułamek-Kozioł, M.; Kocki, J.; Bogucka-Kocka, A.; Januszewski, S.; Bogucki, J.; Czuczwar, S.J.; Pluta, R. Autophagy, mitophagy and apoptotic gene changes in the hippocampal CA1 area in a rat ischemic model of Alzheimer’s disease. Pharm. Rep. 2017, 69, 1289–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.R.; Van Houten, B. SnapShot: Mitochondrial quality control. Cell 2011, 147, 950.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cai, Q.; Tammineni, P. Alterations in Mitochondrial Quality Control in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2016, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anzell, A.R.; Maizy, R.; Przyklenk, K.; Sanderson, T.H. Mitochondrial Quality Control and Disease: Insights into Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 2547–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Reddy, P.H.; Oliver, D.M. Amyloid Beta and Phosphorylated Tau-Induced Defective Autophagy and Mitophagy in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cells 2019, 8, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sekine, S. PINK1 import regulation at a crossroad of mitochondrial fate: The molecular mechanisms of PINK1 import. J. Biochem. 2020, 167, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, N.; Lu, B. Mechanisms and roles of mitophagy in neurodegenerative diseases. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2019, 25, 859–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, G.; Palikaras, K.; Lautrup, S.; Scheibye-Knudsen, M.; Tavernarakis, N.; Fang, E.F. Mitophagy and Neuroprotection. Trends Mol. Med. 2020, 26, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravorty, A.; Jetto, C.T.; Manjithaya, R. Dysfunctional Mitochondria and Mitophagy as Drivers of Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, J.S.; Adriaanse, B.A.; Greig, N.H.; Mattson, M.P.; Cader, M.Z.; Bohr, V.A.; Fang, E.F. Mitophagy and Alzheimer’s Disease: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms. Trends Neurosci. 2017, 40, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Heckmann, B.L.; Teubner, B.J.W.; Tummers, B.; Boada-Romero, E.; Harris, L.; Yang, M.; Guy, C.S.; Zakharenko, S.S.; Green, D.R. LC3-Associated Endocytosis Facilitates β-Amyloid Clearance and Mitigates Neurodegeneration in Murine Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell 2019, 178, 536–551.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kataoka, T.; Holler, N.; Micheau, O.; Martinon, F.; Tinel, A.; Hofmann, K.; Tschopp, J. Bcl-rambo, a novel Bcl-2 homologue that induces apoptosis via its unique C-terminal extension. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 19548–19554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Meng, F.; Sun, N.; Liu, D.; Jia, J.; Xiao, J.; Dai, H. BCL2L13: Physiological and pathological meanings. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakawa, T.; Yamaguchi, O.; Hashimoto, A.; Hikoso, S.; Takeda, T.; Oka, T.; Yasui, H.; Ueda, H.; Akazawa, Y.; Nakayama, H.; et al. Bcl-2-like protein 13 is a mammalian Atg32 homologue that mediates mitophagy and mitochondrial fragmentation. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boumela, I.; Assou, S.; Aouacheria, A.; Haouzi, D.; Dechaud, H.; De Vos, J.; Handyside, A.; Hamamah, S. Involvement of BCL2 family members in the regulation of human oocyte and early embryo survival and death: Gene expression and beyond. Reproduction 2011, 141, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fujiwara, M.; Tian, L.; Le, P.T.; DeMambro, V.E.; Becker, K.A.; Rosen, C.J.; Guntur, A.R. The mitophagy receptor Bcl-2-like protein 13 stimulates adipogenesis by regulating mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and apoptosis in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 12683–12694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadonic, C.; Sabbir, M.G.; Albensi, B.C. Mechanisms of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 6078–6090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adlimoghaddam, A.; Snow, W.M.; Stortz, G.; Perez, C.; Djordjevic, J.; Goertzen, A.L.; Ko, J.H.; Albensi, B.C. Regional hypometabolism in the 3xTg mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 127, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, K.; Munshi, S.; Frank, D.E.; Gibson, G.E. Abnormal Glucose Metabolism in Alzheimer’s Disease: Relation to Autophagy/Mitophagy and Therapeutic Approaches. Neurochem. Res. 2015, 40, 2557–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Albensi, B.C. Dysfunction of mitochondria: Implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2019, 145, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kapogiannis, D.; Mattson, M.P. Disrupted energy metabolism and neuronal circuit dysfunction in cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2011, 10, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dong, Y.; Brewer, G.J. Global Metabolic Shifts in Age and Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Brains Pivot at NAD+/NADH Redox Sites. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019, 71, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marcus, C.; Mena, E.; Subramaniam, R.M. Brain PET in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2014, 39, e413–e426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Róna-Vörös, K.; Weydt, P. The role of PGC-1α in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders. Curr. Drug Targets. 2010, 11, 1262–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenini, G.; Voos, W. Mitochondria as Potential Targets in Alzheimer Disease Therapy: An Update. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Aman, Y.; Adriaanse, B.A.; Cader, M.Z.; Plun-Favreau, H.; Xiao, J.; Fang, E.F. Culprit or Bystander: Defective Mitophagy in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, P.H.; Yin, X.; Manczak, M.; Kumar, S.; Pradeepkiran, J.A.; Vijayan, M.; Reddy, A.P. Mutant APP and amyloid beta-induced defective autophagy, mitophagy, mitochondrial structural and functional changes and synaptic damage in hippocampal neurons from Alzheimer’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 2502–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manczak, M.; Reddy, P.H. Abnormal interaction of VDAC1 with amyloid beta and phosphorylated tau causes mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 5131–5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casley, C.S.; Canevari, L.; Land, J.M.; Clark, J.B.; Sharpe, M.A. Beta-amyloid inhibits integrated mitochondrial respiration and key enzyme activities. J. Neurochem. 2002, 80, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillement, L.; Lecanu, L.; Yao, W.; Greeson, J.; Papadopoulos, V. The spirostenol (22R, 25R)-20alpha-spirost-5-en-3beta-yl hexanoate blocks mitochondrial uptake of Abeta in neuronal cells and prevents Abeta-induced impairment of mitochondrial function. Steroids 2006, 71, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picone, P.; Nuzzo, D.; Caruana, L.; Scafidi, V.; Di Carlo, M. Mitochondrial dysfunction: Different routes to Alzheimer’s disease therapy. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 780179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Du, H.; Yan, S.S. Mitochondrial permeability transition pore in Alzheimer’s disease: Cyclophilin D and amyloid beta. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1802, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rao, V.K.; Carlson, E.A.; Yan, S.S. Mitochondrial permeability transition pore is a potential drug target for neurodegeneration. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1842, 1267–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Park, J.; Choi, H.; Min, J.S.; Kim, B.; Lee, S.R.; Yun, J.W.; Choi, M.S.; Chang, K.T.; Lee, D.S. Loss of mitofusin 2 links beta-amyloid-mediated mitochondrial fragmentation and Cdk5-induced oxidative stress in neuron cells. J. Neurochem. 2015, 132, 687–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, D.I.; Lee, K.H.; Gabr, A.A.; Choi, G.E.; Kim, J.S.; Ko, S.H.; Han, H.J. Aβ-Induced Drp1 phosphorylation through Akt activation promotes excessive mitochondrial fission leading to neuronal apoptosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1863, 2820–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrenius, S.; Gogvadze, V.; Zhivotovsky, B. Calcium and mitochondria in the regulation of cell death. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 460, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, S.; Wood-Kaczmar, A.; Yao, Z.; Plun-Favreau, H.; Deas, E.; Klupsch, K.; Downward, J.; Latchman, D.S.; Tabrizi, S.J.; Wood, N.W.; et al. PINK1-associated Parkinson’s disease is caused by neuronal vulnerability to calcium-induced cell death. Mol. Cell. 2009, 33, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Area-Gomez, E.; de Groof, A.; Bonilla, E.; Montesinos, J.; Tanji, K.; Boldogh, I.; Pon, L.; Schon, E.A. A key role for MAM in mediating mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer disease. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheng, J.; Liao, Y.; Dong, Y.; Hu, H.; Yang, N.; Kong, X.; Li, S.; Li, X.; Guo, J.; Qin, L. Microglial autophagy defect causes parkinson disease-like symptoms by accelerating inflammasome activation in mice. Autophagy 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.H.; Bastianetto, S.; Mennicken, F.; Ma, W.; Kar, S. Amyloid beta peptide induces tau phosphorylation and loss of cholinergic neurons in rat primary septal cultures. Neuroscience 2002, 115, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garwood, C.J.; Pooler, A.M.; Atherton, J.; Hanger, D.P.; Noble, W. Astrocytes are important mediators of Abeta-induced neurotoxicity and tau phosphorylation in primary culture. Cell Death Dis. 2011, 2, e167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perez, M.J.; Jara, C.; Quintanilla, R.A. Contribution of Tau Pathology to Mitochondrial Impairment in Neurodegeneration. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manczak, M.; Reddy, P.H. Abnormal interaction between the mitochondrial fission protein Drp1 and hyperphosphorylated tau in Alzheimer’s disease neurons: Implications for mitochondrial dysfunction and neuronal damage. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 2538–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ittner, L.M.; Fath, T.; Ke, Y.D.; Bi, M.; van Eersel, J.; Li, K.M.; Gunning, P.; Gotz, J. Parkinsonism and impaired axonal transport in a mouse model of frontotemporal dementia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 15997–16002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mandelkow, E.M.; Mandelkow, E. Biochemistry and cell biology of tau protein in neurofibrillary degeneration. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a006247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopeikina, K.J.; Carlson, G.A.; Pitstick, R.; Ludvigson, A.E.; Peters, A.; Luebke, J.I.; Koffie, R.M.; Frosch, M.P.; Hyman, B.T.; Spires-Jones, T.L. Tau accumulation causes mitochondrial distribution deficits in neurons in a mouse model of tauopathy and in human Alzheimer’s disease brain. Am. J. Pathol. 2011, 179, 2071–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreadis, A. Tau gene alternative splicing: Expression patterns, regulation and modulation of function in normal brain and neurodegenerative diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2005, 1739, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leon-Espinosa, G.; Garcia, E.; Garcia-Escudero, V.; Hernandez, F.; Defelipe, J.; Avila, J. Changes in tau phosphorylation in hibernating rodents. J. Neurosci. Res. 2013, 91, 954–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amadoro, G.; Corsetti, V.; Stringaro, A.; Colone, M.; D’Aguanno, S.; Meli, G.; Ciotti, M.; Sancesario, G.; Cattaneo, A.; Bussani, R.; et al. A NH2 tau fragment targets neuronal mitochondria at AD synapses: Possible implications for neurodegeneration. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2010, 21, 445–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, X.C.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Z.H.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.P.; Feng, Q.; Wang, Q.; Ye, K.; Liu, G.P.; et al. Human wild-type full-length tau accumulation disrupts mitochondrial dynamics and the functions via increasing mitofusins. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DuBoff, B.; Gotz, J.; Feany, M.B. Tau promotes neurodegeneration via DRP1 mislocalization in vivo. Neuron 2012, 75, 618–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Itoh, K.; Nakamura, K.; Iijima, M.; Sesaki, H. Mitochondrial dynamics in neurodegeneration. Trends Cell Biol. 2013, 23, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cummins, N.; Tweedie, A.; Zuryn, S.; Bertran-Gonzalez, J.; Gotz, J. Disease-associated tau impairs mitophagy by inhibiting Parkin translocation to mitochondria. EMBO J. 2019, 38, e99360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespo-Biel, N.; Theunis, C.; Van Leuven, F. Protein tau: Prime cause of synaptic and neuronal degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2012, 2012, 251426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kolarova, M.; Garcia-Sierra, F.; Bartos, A.; Ricny, J.; Ripova, D. Structure and pathology of tau protein in Alzheimer disease. Int. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2012, 2012, 731526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Knott, A.B.; Bossy-Wetzel, E. Impairing the mitochondrial fission and fusion balance: A new mechanism of neurodegeneration. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1147, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Höglinger, G.U.; Lannuzel, A.; Khondiker, M.E.; Michel, P.P.; Duyckaerts, C.; Féger, J.; Champy, P.; Prigent, A.; Medja, F.; Lombes, A.; et al. The mitochondrial complex I inhibitor rotenone triggers a cerebral tauopathy. J. Neurochem. 2005, 95, 930–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.M.; Park, J.; Kim, S.H.; Jung, Y.K. Emerging perspectives on mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. BMB Rep. 2020, 53, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Tian, J.; Du, H. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Synaptic Transmission Failure in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017, 57, 1071–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cheng, Y.; Bai, F. The Association of Tau with Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, A.; Aruoma, O.I. Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease: A Nutritional Toxicology Perspective of the Impact of Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Nutrigenomics and Environmental Chemicals. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2020, 39, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fukui, H.; Diaz, F.; Garcia, S.; Moraes, C.T. Cytochrome c oxidase deficiency in neurons decreases both oxidative stress and amyloid formation in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 14163–14168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perez Ortiz, J.M.; Swerdlow, R.H. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: Role in pathogenesis and novel therapeutic opportunities. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 3489–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Jeong, Y.Y. Mitophagy in Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Age-Related Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cells 2020, 9, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Castellazzi, M.; Patergnani, S.; Donadio, M.; Giorgi, C.; Bonora, M.; Bosi, C.; Brombo, G.; Pugliatti, M.; Seripa, D.; Zuliani, G.; et al. Autophagy and mitophagy biomarkers are reduced in sera of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sorrentino, V.; Romani, M.; Mouchiroud, L.; Beck, J.S.; Zhang, H.; D’Amico, D.; Moullan, N.; Potenza, F.; Schmid, A.W.; Rietsch, S.; et al. Enhancing mitochondrial proteostasis reduces amyloid-β proteotoxicity. Nature 2017, 552, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coskun, P.E.; Beal, M.F.; Wallace, D.C. Alzheimer’s brains harbor somatic mtDNA control-region mutations that suppress mitochondrial transcription and replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 10726–10731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoekstra, J.G.; Hipp, M.J.; Montine, T.J.; Kennedy, S.R. Mitochondrial DNA mutations increase in early stage Alzheimer disease and are inconsistent with oxidative damage. Ann. Neurol. 2016, 80, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malfatti, M.C.; Antoniali, G.; Codrich, M.; Burra, S.; Mangiapane, G.; Dalla, E.; Tell, G. New perspectives in cancer biology from a study of canonical and non-canonical functions of base excision repair proteins with a focus on early steps. Mutagenesis 2020, 35, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gredilla, R.; Garm, C.; Stevnsner, T. Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA repair in selected eukaryotic aging model systems. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2012, 2012, 282438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chow, H.M.; Herrup, K. Genomic integrity and the ageing brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 672–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Song, H.; Croteau, D.L.; Akbari, M.; Bohr, V.A. Genome instability in Alzheimer disease. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2017, 161 (Pt A), 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choy, K.R.; Watters, D.J. Neurodegeneration in ataxia-telangiectasia: Multiple roles of ATM kinase in cellular homeostasis. Dev. Dyn. 2018, 247, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Amirifar, P.; Ranjouri, M.R.; Yazdani, R.; Abolhassani, H.; Aghamohammadi, A. Ataxia-telangiectasia: A review of clinical features and molecular pathology. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2019, 30, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Liu, J.; Gu, G.; Han, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, W. Impact of neural stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles on mitochondrial dysfunction, sirtuin 1 level, and synaptic deficits in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2020, 154, 502–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.H. Mechanisms and disease implications of sirtuin-mediated autophagic regulation. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019, 51, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Esteves, A.R.; Filipe, F.; Magalhães, J.D.; Silva, D.F.; Cardoso, S.M. The Role of Beclin-1 Acetylation on Autophagic Flux in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 5654–5670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Yan, W.Y.; Lei, Y.H.; Wan, Z.; Hou, Y.Y.; Sun, L.K.; Zhou, J.P. SIRT3 Regulation of Mitochondrial Quality Control in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Theurey, P.; Connolly, N.M.C.; Fortunati, I.; Basso, E.; Lauwen, S.; Ferrante, C.; Moreira Pinho, C.; Joselin, A.; Gioran, A.; Bano, D.; et al. Systems biology identifies preserved integrity but impaired metabolism of mitochondria due to a glycolytic defect in Alzheimer’s disease neurons. Aging Cell 2019, 18, e12924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, M.; Ying, W. NAD(+) Deficiency Is a Common Central Pathological Factor of a Number of Diseases and Aging: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2019, 30, 890–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Lautrup, S.; Cordonnier, S.; Wang, Y.; Croteau, D.L.; Zavala, E.; Zhang, Y.; Moritoh, K.; O’Connell, J.F.; Baptiste, B.A.; et al. NAD+ supplementation normalizes key Alzheimer’s features and DNA damage responses in a new AD mouse model with introduced DNA repair deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E1876–E1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Severini, C.; Barbato, C.; Di Certo, M.G.; Gabanella, F.; Petrella, C.; Di Stadio, A.; de Vincentiis, M.; Polimeni, A.; Ralli, M.; Greco, A. Alzheimer’s disease: New concepts on the role of autoimmunity and of NLRP3 inflammasome in the pathogenesis of the disease. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2020, 21, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, G. Mechanisms of NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation: Its Role in the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurochem. Res. 2020, 45, 2560–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkowski, E.; Andreasen, N.; Tarkowski, A.; Blennow, K. Intrathecal inflammation precedes development of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2003, 74, 1200–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.L.; Zinn, R.; Hohensinn, B.; Konen, L.M.; Beynon, S.B.; Tan, R.P.; Clark, I.A.; Abdipranoto, A.; Vissel, B. Neuroinflammation and neuronal loss precede Aβ plaque deposition in the hAPP-J20 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ng, A.; Tam, W.W.; Zhang, M.W.; Ho, C.S.; Husain, S.F.; McIntyre, R.S.; Ho, R.C. IL-1β, IL-6, TNF- α and CRP in Elderly Patients with Depression or Alzheimer’s disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroder, K.; Tschopp, J. The inflammasomes. Cell 2010, 140, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gustin, A.; Kirchmeyer, M.; Koncina, E.; Felten, P.; Losciuto, S.; Heurtaux, T.; Tardivel, A.; Heuschling, P.; Dostert, C. NLRP3 Inflammasome Is Expressed and Functional in Mouse Brain Microglia but Not in Astrocytes. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Saresella, M.; La Rosa, F.; Piancone, F.; Zoppis, M.; Marventano, I.; Calabrese, E.; Rainone, V.; Nemni, R.; Mancuso, R.; Clerici, M. The NLRP3 and NLRP1 inflammasomes are activated in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2016, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Halle, A.; Hornung, V.; Petzold, G.C.; Stewart, C.R.; Monks, B.G.; Reinheckel, T.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; Latz, E.; Moore, K.J.; Golenbock, D.T. The NALP3 inflammasome is involved in the innate immune response to amyloid-beta. Nat. Immunol. 2008, 9, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Inflammation. Available online: https://www.alzforum.org/therapeutics/timeline/inflammation (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Sarlus, H.; Heneka, M.T. Microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 3240–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Gómez, J.A.; Kavanagh, E.; Engskog-Vlachos, P.; Engskog, M.K.; Herrera, A.J.; Espinosa-Oliva, A.M.; Joseph, B.; Hajji, N.; Venero, J.L.; Burguillos, M.A. Microglia: Agents of the CNS Pro-inflammatory response. Cells 2020, 9, 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augusto-Oliveira, M.; Arrifano, G.P.; Lopes-Araújo, A.; Santos-Sacramento, L.; Takeda, P.Y.; Anthony, D.C.; Malva, J.O.; Crespo-Lopez, M.E. What Do Microglia Really Do in Healthy Adult Brain? Cells 2019, 8, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tremblay, M.-È.; Stevens, B.; Sierra, A.; Wake, H.; Bessis, A.; Nimmerjahn, A. The role of microglia in the healthy brain. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 16064–16069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, T.L.; Carrier, M.; Tremblay, M.-È. Physiology of Microglia. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 1175, pp. 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmerjahn, A.; Kirchhoff, F.; Helmchen, F. Resting microglial cells are highly dynamic surveillants of brain parenchyma in vivo. Science 2005, 308, 1314–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Finsen, B.; Myhre, C.L.; Thygesen, C.; Villadsen, B.; Vollerup, J.; Ilkjær, L.; Jensen, K.T.; Grebing, M.; Zhao, S.; Khan, A.M. Microglia express insulin-like growth factor-1 in the hippocampus of aged APPswe/PS1dE9 transgenic mice. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2019, 13, 308. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J.; Valin, K.L.; Dixon, M.L.; Leavenworth, J.W. The role of microglia and macrophages in CNS homeostasis, autoimmunity, and cancer. J. Immunol. Res. 2017, 2017, 5150678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loughlin, A.J.; Woodroofe, M.N.; Cuzner, M.L. Regulation of Fc receptor and major histocompatibility complex antigen expression on isolated rat microglia by tumour necrosis factor, interleukin-1 and lipopolysaccharide: Effects on interferon-gamma induced activation. Immunology 1992, 75, 170–175. [Google Scholar]

- Okun, E.; Mattson, M.P.; Arumugam, T.V. Involvement of Fc receptors in disorders of the central nervous system. Neuromolecular Med. 2010, 12, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adlimoghaddam, A.; Odero, G.G.; Glazner, G.; Turner, R.S.; Albensi, B.C. Nilotinib improves bioenergetic profiling in brain astroglia in the 3xTg mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Aging Dis. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Adlimoghaddam, A.; Albensi, B.C. The nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathway is involved in ammonia-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. Mitochondrion 2020, 57, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crehan, H.; Hardy, J.; Pocock, J. Blockage of CR1 prevents activation of rodent microglia. Neurobiol. Dis. 2013, 54, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litvinchuk, A.; Wan, Y.W.; Swartzlander, D.B.; Chen, F.; Cole, A.; Propson, N.E.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, B.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, H. Complement C3aR Inactivation Attenuates Tau Pathology and Reverses an Immune Network Deregulated in Tauopathy Models and Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuron 2018, 100, 1337–1353.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, J.; Li, R.; Mastroeni, D.; Grover, A.; Leonard, B.; Ahern, G.; Cao, P.; Kolody, H.; Vedders, L.; Kolb, W.P.; et al. Peripheral clearance of amyloid beta peptide by complement C3-dependent adherence to erythrocytes. Neurobiol. Aging 2006, 27, 1733–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, C.R.; Falsig, J.; Stavenhagen, J.B.; Christensen, S.; Kartberg, F.; Rosenqvist, N.; Finsen, B.; Pedersen, J.T. Antibody-mediated clearance of tau in primary mouse microglial cultures requires Fcgamma-receptor binding and functional lysosomes. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jin, C.Y.; Moon, D.O.; Lee, K.J.; Kim, M.O.; Lee, J.D.; Choi, Y.H.; Park, Y.M.; Kim, G.Y. Piceatannol attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced NF-kappaB activation and NF-kappaB-related proinflammatory mediators in BV2 microglia. Pharmacol. Res. 2006, 54, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Shapiro, S.; Goldman, D.L.; Casadevall, A.; Scharff, M.; Lee, S.C. Fcgamma receptor I- and III-mediated macrophage inflammatory protein 1alpha induction in primary human and murine microglia. Infect. Immun. 2002, 70, 5177–5184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Congdon, E.E.; Chukwu, J.E.; Shamir, D.B.; Deng, J.; Ujla, D.; Sait, H.B.R.; Neubert, T.A.; Kong, X.P.; Sigurdsson, E.M. Tau antibody chimerization alters its charge and binding, thereby reducing its cellular uptake and efficacy. EBioMedicine 2019, 42, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bard, F.; Cannon, C.; Barbour, R.; Burke, R.L.; Games, D.; Grajeda, H.; Guido, T.; Hu, K.; Huang, J.; Johnson-Wood, K.; et al. Peripherally administered antibodies against amyloid beta-peptide enter the central nervous system and reduce pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Nat. Med. 2000, 6, 916–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilcock, D.M.; DiCarlo, G.; Henderson, D.; Jackson, J.; Clarke, K.; Ugen, K.E.; Gordon, M.N.; Morgan, D. Intracranially administered anti-Abeta antibodies reduce beta-amyloid deposition by mechanisms both independent of and associated with microglial activation. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 3745–3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ittner, A.; Bertz, J.; Suh, L.S.; Stevens, C.H.; Gotz, J.; Ittner, L.M. Tau-targeting passive immunization modulates aspects of pathology in tau transgenic mice. J. Neurochem. 2015, 132, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Le Pichon, C.E.; Adolfsson, O.; Gafner, V.; Pihlgren, M.; Lin, H.; Solanoy, H.; Brendza, R.; Ngu, H.; Foreman, O.; et al. Antibody-Mediated Targeting of Tau In Vivo Does Not Require Effector Function and Microglial Engagement. Cell Rep. 2016, 16, 1690–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vitale, F.; Giliberto, L.; Ruiz, S.; Steslow, K.; Marambaud, P.; d’Abramo, C. Anti-tau conformational scFv MC1 antibody efficiently reduces pathological tau species in adult JNPL3 mice. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2018, 6, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornemann, K.D.; Wiederhold, K.H.; Pauli, C.; Ermini, F.; Stalder, M.; Schnell, L.; Sommer, B.; Jucker, M.; Staufenbiel, M. Aβ-induced inflammatory processes in microglia cells of APP23 transgenic mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2001, 158, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Brazil, M.I.; Irizarry, M.C.; Hyman, B.T.; Maxfield, F.R. Uptake of fibrillar beta-amyloid by microglia isolated from MSR-A (type I and type II) knockout mice. Neuroreport 2001, 12, 1151–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coraci, I.S.; Husemann, J.; Berman, J.W.; Hulette, C.; Dufour, J.H.; Campanella, G.K.; Luster, A.D.; Silverstein, S.C.; El-Khoury, J.B. CD36, a class B scavenger receptor, is expressed on microglia in Alzheimer’s disease brains and can mediate production of reactive oxygen species in response to beta-amyloid fibrils. Am. J. Pathol. 2002, 160, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khoury, J.B.; Moore, K.J.; Means, T.K.; Leung, J.; Terada, K.; Toft, M.; Freeman, M.W.; Luster, A.D. CD36 mediates the innate host response to beta-amyloid. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 197, 1657–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moore, K.J.; El Khoury, J.; Medeiros, L.A.; Terada, K.; Geula, C.; Luster, A.D.; Freeman, M.W. A CD36-initiated signaling cascade mediates inflammatory effects of beta-amyloid. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 47373–47379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stewart, C.R.; Stuart, L.M.; Wilkinson, K.; van Gils, J.M.; Deng, J.; Halle, A.; Rayner, K.J.; Boyer, L.; Zhong, R.; Frazier, W.A.; et al. CD36 ligands promote sterile inflammation through assembly of a Toll-like receptor 4 and 6 heterodimer. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Onyango, I.G.; Tuttle, J.B.; Bennett, J.P., Jr. Altered intracellular signaling and reduced viability of Alzheimer’s disease neuronal cybrids is reproduced by beta-amyloid peptide acting through receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE). Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2005, 29, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deane, R.; Du Yan, S.; Submamaryan, R.K.; LaRue, B.; Jovanovic, S.; Hogg, E.; Welch, D.; Manness, L.; Lin, C.; Yu, J.; et al. RAGE mediates amyloid-beta peptide transport across the blood-brain barrier and accumulation in brain. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Origlia, N.; Bonadonna, C.; Rosellini, A.; Leznik, E.; Arancio, O.; Yan, S.S.; Domenici, L. Microglial receptor for advanced glycation end product-dependent signal pathway drives beta-amyloid-induced synaptic depression and long-term depression impairment in entorhinal cortex. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 11414–11425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessa, L.; Gatti, E.; Zeni, F.; Antonelli, A.; Catucci, A.; Koch, M.; Pompilio, G.; Fritz, G.; Raucci, A.; Bianchi, M.E. The receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE) is only present in mammals, and belongs to a family of cell adhesion molecules (CAMs). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juranek, J.; Ray, R.; Banach, M.; Rai, V. Receptor for advanced glycation end-products in neurodegenerative diseases. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 26, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaney, M.O.; Stine, W.B.; Kokjohn, T.A.; Kuo, Y.M.; Esh, C.; Rahman, A.; Luehrs, D.C.; Schmidt, A.M.; Stern, D.; Yan, S.D.; et al. RAGE and amyloid beta interactions: Atomic force microscopy and molecular modeling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2005, 1741, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yan, S.S.; Chen, D.; Yan, S.; Guo, L.; Du, H.; Chen, J.X. RAGE is a key cellular target for Abeta-induced perturbation in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Biosci. 2012, 4, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Lue, L.F.; Yan, S.; Xu, H.; Luddy, J.S.; Chen, D.; Walker, D.G.; Stern, D.M.; Yan, S.; Schmidt, A.M.; et al. RAGE-dependent signaling in microglia contributes to neuroinflammation, Abeta accumulation, and impaired learning/memory in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 2010, 24, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yan, S.D.; Chen, X.; Fu, J.; Chen, M.; Zhu, H.; Roher, A.; Slattery, T.; Zhao, L.; Nagashima, M.; Morser, J.; et al. RAGE and amyloid-beta peptide neurotoxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 1996, 382, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deane, R.; Singh, I.; Sagare, A.P.; Bell, R.D.; Ross, N.T.; LaRue, B.; Love, R.; Perry, S.; Paquette, N.; Deane, R.J.; et al. A multimodal RAGE-specific inhibitor reduces amyloid beta-mediated brain disorder in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 1377–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, S.W.; Kim, J.H.; Park, S.M.; Moon, M.; Lee, K.H.; Park, K.H.; Park, W.J.; Kim, J.H. RAGE mediated intracellular Aβ uptake contributes to the breakdown of tight junction in retinal pigment epithelium. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 35263–35273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, Y.; Ulland, T.K.; Colonna, M. TREM2-Dependent Effects on Microglia in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guerreiro, R.; Wojtas, A.; Bras, J.; Carrasquillo, M.; Rogaeva, E.; Majounie, E.; Cruchaga, C.; Sassi, C.; Kauwe, J.S.; Younkin, S.; et al. TREM2 variants in Alzheimer’s disease. New Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frank, S.; Burbach, G.J.; Bonin, M.; Walter, M.; Streit, W.; Bechmann, I.; Deller, T. TREM2 is upregulated in amyloid plaque-associated microglia in aged APP23 transgenic mice. Glia 2008, 56, 1438–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cella, M.; Mallinson, K.; Ulrich, J.D.; Young, K.L.; Robinette, M.L.; Gilfillan, S.; Krishnan, G.M.; Sudhakar, S.; Zinselmeyer, B.H.; et al. TREM2 lipid sensing sustains the microglial response in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Cell 2015, 160, 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jiang, T.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, Y.D.; Zhou, J.S.; Gao, Q.; Zhu, X.C.; Shi, J.Q.; Lu, H.; Tan, L.; Yu, J.T. TREM2 Overexpression has No Improvement on Neuropathology and Cognitive Impairment in Aging APPswe/PS1dE9 Mice. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyns, C.E.G.; Ulrich, J.D.; Finn, M.B.; Stewart, F.R.; Koscal, L.J.; Remolina Serrano, J.; Robinson, G.O.; Anderson, E.; Colonna, M.; Holtzman, D.M. TREM2 deficiency attenuates neuroinflammation and protects against neurodegeneration in a mouse model of tauopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 11524–11529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bemiller, S.M.; McCray, T.J.; Allan, K.; Formica, S.V.; Xu, G.; Wilson, G.; Kokiko-Cochran, O.N.; Crish, S.D.; Lasagna-Reeves, C.A.; Ransohoff, R.M.; et al. TREM2 deficiency exacerbates tau pathology through dysregulated kinase signaling in a mouse model of tauopathy. Mol. Neurodegener. 2017, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, T.R.; Hirsch, A.M.; Broihier, M.L.; Miller, C.M.; Neilson, L.E.; Ransohoff, R.M.; Lamb, B.T.; Landreth, G.E. Disease Progression-Dependent Effects of TREM2 Deficiency in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jay, T.R.; Miller, C.M.; Cheng, P.J.; Graham, L.C.; Bemiller, S.; Broihier, M.L.; Xu, G.; Margevicius, D.; Karlo, J.C.; Sousa, G.L.; et al. TREM2 deficiency eliminates TREM2+ inflammatory macrophages and ameliorates pathology in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. J. Exp. Med. 2015, 212, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, J.D.; Finn, M.B.; Wang, Y.; Shen, A.; Mahan, T.E.; Jiang, H.; Stewart, F.R.; Piccio, L.; Colonna, M.; Holtzman, D.M. Altered microglial response to Abeta plaques in APPPS1-21 mice heterozygous for TREM2. Mol. Neurodegener. 2014, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Griciuc, A.; Serrano-Pozo, A.; Parrado, A.R.; Lesinski, A.N.; Asselin, C.N.; Mullin, K.; Hooli, B.; Choi, S.H.; Hyman, B.T.; Tanzi, R.E. Alzheimer’s disease risk gene CD33 inhibits microglial uptake of amyloid beta. Neuron 2013, 78, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Doens, D.; Fernandez, P.L. Microglia receptors and their implications in the response to amyloid beta for Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. J. Neuroinflammation 2014, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, M.; Jin, J.; Lim, J.E.; Kou, J.; Pattanayak, A.; Rehman, J.A.; Kim, H.D.; Tahara, K.; Lalonde, R.; Fukuchi, K. TLR4 mutation reduces microglial activation, increases Abeta deposits and exacerbates cognitive deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroinflammation 2011, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yamamoto, M.; Takeda, K. Current views of toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2010, 2010, 240365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jana, M.; Palencia, C.A.; Pahan, K. Fibrillar amyloid-beta peptides activate microglia via TLR2: Implications for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 7254–7262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.G.; Tang, T.M.; Lue, L.F. Increased expression of toll-like receptor 3, an anti-viral signaling molecule, and related genes in Alzheimer’s disease brains. Exp. Neurol. 2018, 309, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.A.; Elmaoued, R.A.; Davis, A.S.; Kyei, G.; Deretic, V. Toll-like receptors control autophagy. EMBO J. 2008, 27, 1110–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anderson, K.V. Toll signaling pathways in the innate immune response. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2000, 12, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, L.A.; Greene, C. Signal transduction pathways activated by the IL-1 receptor family: Ancient signaling machinery in mammals, insects, and plants. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1998, 63, 650–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Ghosh, S. Toll-like receptor-mediated NF-kappaB activation: A phylogenetically conserved paradigm in innate immunity. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 107, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krasemann, S.; Madore, C.; Cialic, R.; Baufeld, C.; Calcagno, N.; El Fatimy, R.; Beckers, L.; O’Loughlin, E.; Xu, Y.; Fanek, Z.; et al. The TREM2-APOE Pathway Drives the Transcriptional Phenotype of Dysfunctional Microglia in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Immunity 2017, 47, 566–581.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Konttinen, H.; Cabral-da-Silva, M.E.C.; Ohtonen, S.; Wojciechowski, S.; Shakirzyanova, A.; Caligola, S.; Giugno, R.; Ishchenko, Y.; Hernández, D.; Fazaludeen, M.F.; et al. PSEN1DeltaE9, APPswe, and APOE4 Confer Disparate Phenotypes in Human iPSC-Derived Microglia. Stem Cell Rep. 2019, 13, 669–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prasad, H.; Rao, R. Amyloid clearance defect in ApoE4 astrocytes is reversed by epigenetic correction of endosomal pH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E6640–E6649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shi, Y.; Manis, M.; Long, J.; Wang, K.; Sullivan, P.M.; Remolina Serrano, J.; Hoyle, R.; Holtzman, D.M. Microglia drive APOE-dependent neurodegeneration in a tauopathy mouse model. J. Exp. Med. 2019, 216, 2546–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloske, C.M.; Wilcock, D.M. The Important Interface Between Apolipoprotein E and Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Yamada, K.; Liddelow, S.A.; Smith, S.T.; Zhao, L.; Luo, W.; Tsai, R.M.; Spina, S.; Grinberg, L.T.; Rojas, J.C.; et al. ApoE4 markedly exacerbates tau-mediated neurodegeneration in a mouse model of tauopathy. Nature 2017, 549, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, J.R.; Tang, W.; Wang, H.; Vitek, M.P.; Bennett, E.R.; Sullivan, P.M.; Warner, D.S.; Laskowitz, D.T. APOE genotype and an ApoE-mimetic peptide modify the systemic and central nervous system inflammatory response. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 48529–48533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zlokovic, B.V. Cerebrovascular effects of apolipoprotein E: Implications for Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2013, 70, 440–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Z.; Guo, Z.; Zhong, J.; Cheng, C.; Huang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Tang, S.; Luo, C.; Peng, X.; Wu, H.; et al. ApoE Influences the Blood-Brain Barrier Through the NF-kappaB/MMP-9 Pathway After Traumatic Brain Injury. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bell, R.D.; Winkler, E.A.; Singh, I.; Sagare, A.P.; Deane, R.; Wu, Z.; Holtzman, D.M.; Betsholtz, C.; Armulik, A.; Sallstrom, J.; et al. Apolipoprotein E controls cerebrovascular integrity via cyclophilin A. Nature 2012, 485, 512–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Chen, X.; Wei, X.; Bales, K.R.; Berg, D.T.; Paul, S.M.; Farlow, M.R.; Maloney, B.; Ge, Y.W.; Lahiri, D.K. NF-(kappa)B mediates amyloid beta peptide-stimulated activity of the human apolipoprotein E gene promoter in human astroglial cells. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2005, 136, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gratuze, M.; Leyns, C.E.G.; Holtzman, D.M. New insights into the role of TREM2 in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2018, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ennerfelt, H.E.; Lukens, J.R. The role of innate immunity in Alzheimer’s disease. Immunol. Rev. 2020, 297, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merino, J.J.; Muneton-Gomez, V.; Alvarez, M.I.; Toledano-Diaz, A. Effects of CX3CR1 and Fractalkine Chemokines in Amyloid Beta Clearance and p-Tau Accumulation in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) Rodent Models: Is Fractalkine a Systemic Biomarker for AD? Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2016, 13, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, A.E.; Pioro, E.P.; Sasse, M.E.; Kostenko, V.; Cardona, S.M.; Dijkstra, I.M.; Huang, D.; Kidd, G.; Dombrowski, S.; Dutta, R.; et al. Control of microglial neurotoxicity by the fractalkine receptor. Nat. Neurosci. 2006, 9, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zhao, W.; Guo, Y.; Xu, J.; Yin, M. CX3CL1/CX3CR1 in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Target for Neuroprotection. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 8090918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Febinger, H.Y.; Thomasy, H.E.; Pavlova, M.N.; Ringgold, K.M.; Barf, P.R.; George, A.M.; Grillo, J.N.; Bachstetter, A.D.; Garcia, J.A.; Cardona, A.E.; et al. Time-dependent effects of CX3CR1 in a mouse model of mild traumatic brain injury. J. Neuroinflammation 2015, 12, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cho, S.H.; Sun, B.; Zhou, Y.; Kauppinen, T.M.; Halabisky, B.; Wes, P.; Ransohoff, R.M.; Gan, L. CX3CR1 protein signaling modulates microglial activation and protects against plaque-independent cognitive deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 32713–32722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bhaskar, K.; Konerth, M.; Kokiko-Cochran, O.N.; Cardona, A.; Ransohoff, R.M.; Lamb, B.T. Regulation of tau pathology by the microglial fractalkine receptor. Neuron 2010, 68, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sellner, S.; Paricio-Montesinos, R.; Spiess, A.; Masuch, A.; Erny, D.; Harsan, L.A.; Elverfeldt, D.V.; Schwabenland, M.; Biber, K.; Staszewski, O.; et al. Microglial CX3CR1 promotes adult neurogenesis by inhibiting Sirt 1/p65 signaling independent of CX3CL1. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2016, 4, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nash, B.; Meucci, O. Functions of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in the central nervous system and its regulation by μ-opioid receptors. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2014, 118, 105–128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mao, W.; Yi, X.; Qin, J.; Tian, M.; Jin, G. CXCL12 promotes proliferation of radial glia like cells after traumatic brain injury in rats. Cytokine 2020, 125, 154771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, W.; Yi, X.; Qin, J.; Tian, M.; Jin, G. CXCL12/CXCR4 Axis Improves Migration of Neuroblasts Along Corpus Callosum by Stimulating MMP-2 Secretion After Traumatic Brain Injury in Rats. Neurochem. Res. 2016, 41, 1315–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfilippo, C.; Castrogiovanni, P.; Imbesi, R.; Nunnari, G.; Di Rosa, M. Postsynaptic damage and microglial activation in AD patients could be linked CXCR4/CXCL12 expression levels. Brain Res. 2020, 1749, 147127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, M.E. DAMPs, PAMPs and alarmins: All we need to know about danger. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2007, 81, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, Y.N.; Angelopoulou, E.; Piperi, C.; Othman, I.; Aamir, K.; Shaikh, M.F. Impact of HMGB1, RAGE, and TLR4 in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD): From Risk Factors to Therapeutic Targeting. Cells 2020, 9, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chikhirzhina, E.; Starkova, T.; Beljajev, A.; Polyanichko, A.; Tomilin, A. Functional Diversity of Non-Histone Chromosomal Protein HmgB1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vande Walle, L.; Kanneganti, T.-D.; Lamkanfi, M. HMGB1 release by inflammasomes. Virulence 2011, 2, 162–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sims, G.P.; Rowe, D.C.; Rietdijk, S.T.; Herbst, R.; Coyle, A.J. HMGB1 and RAGE in inflammation and cancer. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 28, 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volchuk, A.; Ye, A.; Chi, L.; Steinberg, B.E.; Goldenberg, N.M. Indirect regulation of HMGB1 release by gasdermin D. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, K.; Han, Y.; Fang, Q.; Huang, C.; Yu, L.; Ge, W.; Xiang, F.; Tao, Y.X.; Cao, H.; Li, J. HMGB1 gene silencing inhibits neuroinflammation via down-regulation of NF-κB signaling in primary hippocampal neurons induced by Aβ(25-35). Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 67, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcão, A.S.; Carvalho, L.A.; Lidónio, G.; Vaz, A.R.; Lucas, S.D.; Moreira, R.; Brites, D. Dipeptidyl Vinyl Sulfone as a Novel Chemical Tool to Inhibit HMGB1/NLRP3-Inflammasome and Inflamma-miRs in Aβ-Mediated Microglial Inflammation. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017, 8, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takata, K.; Takada, T.; Ito, A.; Asai, M.; Tawa, M.; Saito, Y.; Ashihara, E.; Tomimoto, H.; Kitamura, Y.; Shimohama, S. Microglial Amyloid-β1-40 Phagocytosis Dysfunction Is Caused by High-Mobility Group Box Protein-1: Implications for the Pathological Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2012, 2012, 685739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paudel, Y.N.; Shaikh, M.F.; Chakraborti, A.; Kumari, Y.; Aledo-Serrano, Á.; Aleksovska, K.; Alvim, M.K.M.; Othman, I. HMGB1: A Common Biomarker and Potential Target for TBI, Neuroinflammation, Epilepsy, and Cognitive Dysfunction. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fujita, K.; Motoki, K.; Tagawa, K.; Chen, X.; Hama, H.; Nakajima, K.; Homma, H.; Tamura, T.; Watanabe, H.; Katsuno, M.; et al. HMGB1, a pathogenic molecule that induces neurite degeneration via TLR4-MARCKS, is a potential therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cristóvão, J.S.; Gomes, C.M. S100 Proteins in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrak, R.E.; Griffinbc, W.S. The role of activated astrocytes and of the neurotrophic cytokine S100B in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2001, 22, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, J.; Belli, A. S100B in neuropathologic states: The CRP of the brain? J. Neurosci. Res. 2007, 85, 1373–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, M.L.; Camozzato, A.L.; Ferreira, E.D.; Piazenski, I.; Kochhann, R.; Dall’Igna, O.; Mazzini, G.S.; Souza, D.O.; Portela, L.V. Serum levels of S100B and NSE proteins in Alzheimer’s disease patients. J. Neuroinflammation 2010, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bianchi, R.; Kastrisianaki, E.; Giambanco, I.; Donato, R. S100B protein stimulates microglia migration via RAGE-dependent up-regulation of chemokine expression and release. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 7214–7226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sorci, G.; Bianchi, R.; Riuzzi, F.; Tubaro, C.; Arcuri, C.; Giambanco, I.; Donato, R. S100B Protein, A Damage-Associated Molecular Pattern Protein in the Brain and Heart, and Beyond. Cardiovasc. Psychiatry Neurol. 2010, 2010, 656481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, R.; Giambanco, I.; Donato, R. S100B/RAGE-dependent activation of microglia via NF-kappaB and AP-1 Co-regulation of COX-2 expression by S100B, IL-1beta and TNF-alpha. Neurobiol. Aging 2010, 31, 665–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]