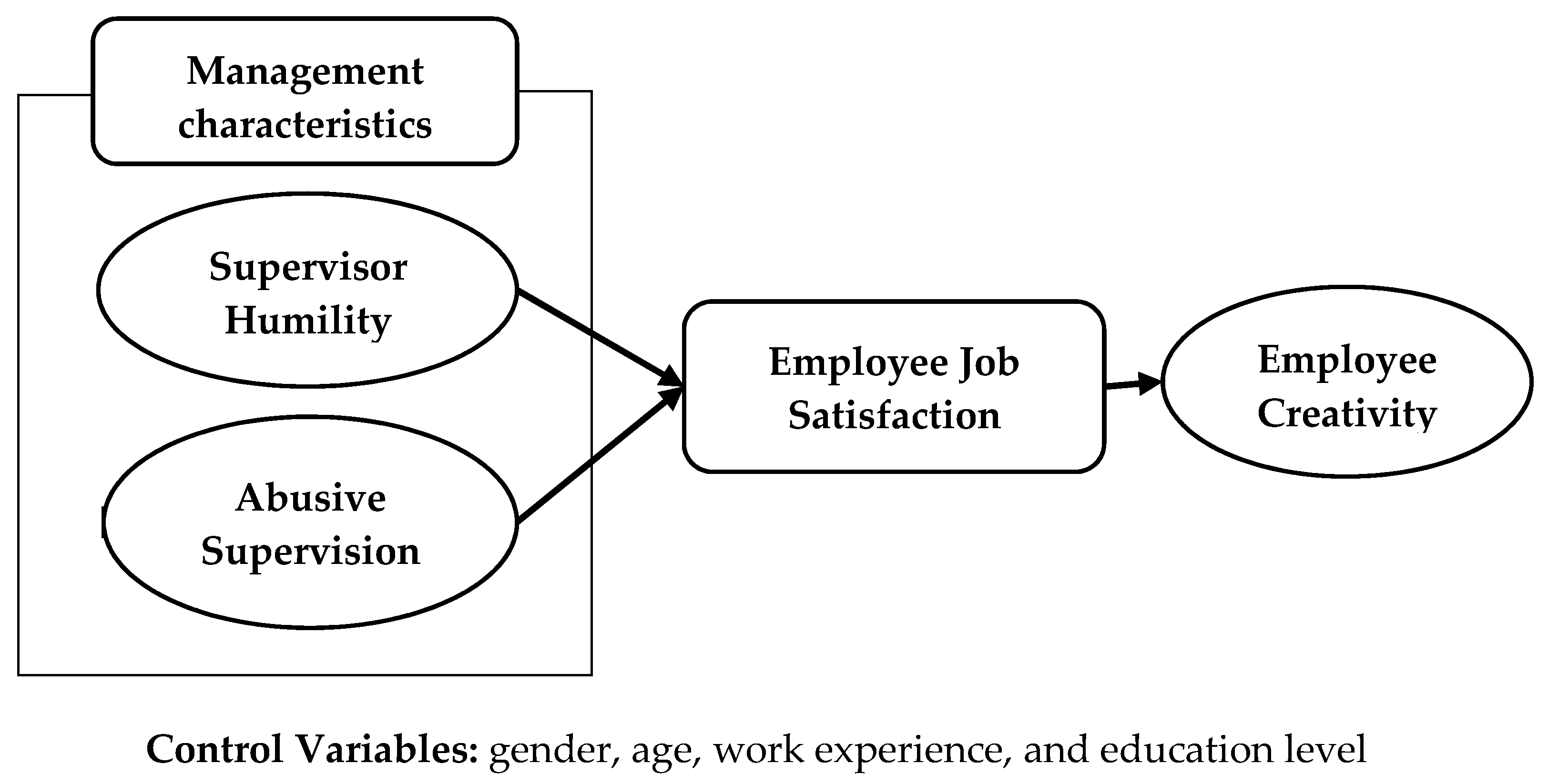

Management Characteristics as Determinants of Employee Creativity: The Mediating Role of Employee Job Satisfaction

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Employee Job Satisfaction

2.2. Hypotheses

2.2.1. Supervisor Humility and Employee Job Satisfaction

2.2.2. Abusive Supervision and Employee Job Satisfaction

2.2.3. Employee Job Satisfaction and Employee Creativity

2.2.4. Mediating Role of Employee Job Satisfaction

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Variables and Measures

3.3. Assessing Common Method Bias and Non-Response Bias

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Measurement Model Results

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary and Implications

5.2. Limitations and Avenues for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lange, D.E.; Busch, T.; Delgado-Ceballos, J. Sustaining Sustainability in Organizations. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 110, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Waite, A.M. Leadership’s influence on innovation and sustainability. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2013, 38, 15–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Jiang, K.; Shalley, C.E.; Keem, S.; Zhou, J. Motivational mechanisms of employee creativity: A meta-analytic examination and theoretical extension of the creativity literature. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2016, 137, 236–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.; Moon, S. Enhancing Employee Creativity for A Sustainable Competitive Advantage through Perceived Human Resource Management Practices and Trust in Management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shalley, C.E.; Gilson, L.L. What leaders need to know: A review of social and contextual factors that can foster or hinder creativity? Leadersh. Q. 2004, 15, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinarski-Peretz, H.; Carmeli, A. Linking care felt to engagement in innovative behaviors in the workplace: The mediating role of psychological conditions. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2011, 5, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, M.; Rockstrom, J.; Raskin, P.; Scoones, I.; Stirling, A.C.; Smith, A.; Thompson, J.; Millstone, E.; Ely, A.; Arond, E.; et al. Transforming innovation for sustainability. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asif, M.; Qing, M.; Hwang, J.; Shi, H. Ethical Leadership, Affective Commitment, WorkEngagement, and Creativity: Testing a Multiple Mediation Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duffy, M.K.; Ganster, D.C.; Shaw, J.D.; Johnson, J.L.; Pagon, M. The social context of undermining behavior at work. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2006, 101, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, S.; Edmondson, A. When values backfire: Leadership, attribution, and disenchantment in a values driven organization. Leadersh. Q. 2006, 17, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Bartol, Z.; Jia, M. Understanding How Leader Humility Enhances Employee Creativity: The Roles of Perspective Taking and Cognitive Reappraisal. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2017, 53, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Liao, H.; Loi, R. The dark side of leadership: A three-level investigation of the cascading effect of abusive supervision on employee creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 1187–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, S.; Yun, S.; Srivastava, A. Evidence for a curvilinear relationship between abusive supervision and creativity in South Korea. Leadersh. Q. 2013, 24, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, B.P.; Johnson, M.D.; Terence, R.M. Expressed humility in Organizations: Implications for performance, teams and Leadership. Organ. Sci. 2013, 24, 1517–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B. Petty tyranny in organizations: A preliminary examination of antecedents and consequences. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 1997, 14, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keashly, L.; Trott, V.; MacLean, L.M. Abusive behavior in the workplace: A preliminary investigation. Violence Vict. 1994, 9, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isen, A.M.; Baron, R.A. Positive affect as a factor in organizational behavior. Res. Organ. Behav. 1991, 13, 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Tepper, B.J. Consequences of Abusive Supervision. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 178–190. [Google Scholar]

- Nerkar, A.A.; McGrath, R.G.; Macmillan, I.C. Three facets of satisfaction and their influence on the performance of innovation teams. J. Bus. Ventur. 1996, 11, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marc, J.E.; Marie-Josee, R. Sustainability in Action: Identifying and Measuring the Key Performance Drivers. Long Range Plan. 2001, 34, 585–604. [Google Scholar]

- Meyerding, S.G.H. Job satisfaction and preferences regarding job characteristics of young professionals in German horticulture. Acta Hortic. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, F.S.; Yolanda, N.A.; Gabriela, T. On the Relationship between Perceived Conflict and Interactional Justice Influenced by Job Satisfaction and Group Identity. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7195. [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg, F.; Bernard, M.; Snyderman, B. The Motivation to Work; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Hollenback, J.R. Control theory and the perception of work environments: The effect of focus of attention on affective and behavioral reactions to work. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1989, 43, 406–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A. What is job satisfaction? Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1989, 4, 336–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.; Nestrom, J.W. Human Behavior at Work: Organizational Behavior, 7th ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1985; p. 109. [Google Scholar]

- Akehurst, G.; Comeche, J.M.; Galindo, M. Job satisfaction and commitment in the entrepreneurial SME. Small Bus. Econ. 2009, 32, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spector, P.E. Measurement of human service staff satisfaction: Development of the job satisfaction survey. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1985, 13, 693–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glisson, C.; Durick, M. Predictors of Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment in Human Service Organizations. Adm. Sci. Q. 1988, 33, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleberg, A.L. Work values and job rewards: A theory of job satisfaction. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1977, 42, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschfield, R.R. Does revising the intrinsic and extrinsic subscales of the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire short form make a difference? Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2000, 60, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S.; Lusch, R.; O’Brien, M. Personal values, leadership styles, job satisfaction and commitment: An exploratory study among retail managers. J. Mark. Channels 2002, 10, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A. The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Dunnette, M.D., Ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1976; pp. 1297–1349. [Google Scholar]

- Skansi, D. Relation of managerial efficiency and leadership styles—Empirical study in Hrvatska elektroprivreda. Management 2000, 5, 51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney, J.P. Humility: Theoretical perspectives, empirical findings, and directions for future research. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 19, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, B.P.; Hekman, D.R. Modeling how to grow: An inductive examination of humble leader behaviors, contingencies, and outcomes. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 787–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fullan, M. Principals as Leaders in a Culture of Change. Educ. Leadersh. 2002, 59, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Aristovnik, A.; Tomazevi, N.; Seljak, J. Factors influencing employee satisfaction in the police service: The case of Slovenia. Pers. Rev. 2014, 43, 209–227. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, S.S.; Spitzmüller, C.; Lin, L.F.; Stanton, J.M.; Smith, P.C.; Ironson, G.H. Shorter can also be better: The abridged job in general scale. Ed. Psych. Meas. 2004, 64, 878–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morris, J.A.; Brotheridge, C.M.; Urbanski, J.C. Bringing humility to leadership: Antecedents and consequences of leader humility. Hum. Relat. 2005, 58, 1323–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, R.; Kaiser, R.B. What we know about leadership. Rev. Gen. Psych. 2005, 9, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dotlich, D.L.; Cairo, P.C. Why CEOs Fail: The 11 Behaviors That Can Derail Your Climb to the Top—And How to Manage Them; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fulmer, R.M.; Conger, J.A. Growing Your Company’s Leaders: How Great Organizations Use Succession Management to Sustain Competitive Advantage; AMACOM: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, S. Why Smart Executives Fail: And What You Can Learn from Their Mistakes; Portfolio Trade: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Misener, T.R.; Haddock, K.S.; Gleaton, J.U.; Ajamieh, A.R. Toward an international measure of job satisfaction. Nurs. Res. 1996, 45, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, V.P.; McCroskey, J.C.; Davis, L.M.; Koontz, K.A. Perceived power as a mediator of management style and employee satisfaction: A preliminary investigation. Commun. Q. 1980, 28, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.; Kacmar, K.M.; Zivnuska, S. An investigation of abusive supervision as a predictor of performance and the meaning of work as a moderator of the relationship. Leadersh. Q. 2007, 18, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, B.J.; Duffy, M.K.; Hoobler, J.; Ensley, M.D. Moderators of the relationships between coworkers’ organizational citizenship behavior and fellow employees’ attitudes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bies, R.J.; Tripp, T.M. Revenge in organizations: The good, the bad, and the ugly. In Dysfunctional Behavior in Organizations: Non-Violent Dysfunctional Behavior; Griffin, R.W., O’Leary-Kelly, A., Gollins, J., Greenwich, G.T., Eds.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1998; pp. 49–67. [Google Scholar]

- Aquino, K.; Griffeth, R.W.; Allen, D.G.; Hornm, P.W. Integrating justice constructs into the turnover process: A test of a referent cognitions model. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 1208–1227. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B. Theory research and managerial applications. In Bass & Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership, 3rd ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Silverthorne, C. Leadership effectiveness, leadership style and employee readiness. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2005, 26, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L.Z.; Tepper, B.J.; Duffy, M.K. Abusive Supervision and Subordinates’ Organizational Citizenship Behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 068–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Richman, J.A.; Flaherty, J.A.; Rospenda, K.M.; Christensen, M.L. Mental health consequences and correlates of reported medical student abuse. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1992, 267, 692–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, K.H.; Sheehan, D.V.; White, K.; Leibowitz, A.; Baldwin, D.C. A pilot study of medical student abuse. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1990, 263, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, A.; Oldham, G.R. Enhancing creativity: managing work contexts for the high potential employee. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1997, 40, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipton, H.J.; West, M.A.; Parkes, C.L.; Dawson, J.F. When promoting positive feelings pays: Aggregate job satisfaction, work design features, and innovation in manufacturing organizations. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2006, 15, 404–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staw, B.M.; Sutton, R.I.; Pelled, L.H. Employee positive emotion and favorable outcomes at the workplace. Organ. Sci. 1994, 5, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, S.; Diener, E.; Lucas, R.; Eunkook, S. Cross-cultural variations in predictors of life satisfaction: Perspectives from needs and values. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 25, 980–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry-Smith, J.E.; Shalley, C.E. The social side of creativity: A static and dynamic social network. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brislin, R. Understanding Culture’s Influence on Behavior; Harcourt Brace College Publishers: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, D.P. Research Methods for Organizational Studies, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, M.G.; Venkatesh, V. Job characteristics and job satisfaction: Understanding the role of Enterprise Resource Planning System implementation. MIS Q. 2010, 34, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ganesan, S.; Weitz, B. The Impact of Staffing Policies on Retail Buyer Job Attitudes and Behaviors. J. Retail. 1996, 72, 31–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M.; Zhou, J. Dual tuning in a supportive context: Joint contributions of positive mood, negative mood, and supervisory behaviors to employee creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 605–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, P.; Steven, M.F. Creative Self-Efficacy: Potential Antecedents and Relationship to Creative Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 1137–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Amabile, T.M. A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. In Research in Organizational Behavior; Staw, B.M., Cummings, L.L., Eds.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1988; Volume 10, pp. 123–167. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedahanov, A.T.; Bozorov, F.; Sung, S.H. Paternalistic Leadership and Innovative Behavior: Psychological Empowerment as a Mediator. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fuller, C.M.; Simmering, M.J.; Atinc, G.; Atinc, Y.; Babin, B.J. Common methods variance detection in business research. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 69, 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R. Specification searches in covariance structure modeling. Psychol. Bull. 1986, 100, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joreskog, K.; Sorbom, D. LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling; Scientific Software International Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K.A. Introduction to Structural Equation Models with Latent Variables; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M.R. Structural equation modeling: Guidelines for determining model fit. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2008, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2001, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, E.M. The link between leadership style, communicator competence, and employee satisfaction. J. Bus. Commun. 2008, 45, 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.J.; Huang, J.W.; Hsiao, Y.C. Knowledge management and innovativeness: The role of organizational climate and structure. Int. J. Manpow. 2010, 31, 848–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northouse, P.G. Leadership: Theory and Practice, 7th ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jennifer, L.R.; Julian, B. Greening organizations through leaders’ influence on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 176–194. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeyi, M.J.B. Transformational vs transactional leadership with examples. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 6, 191–193. [Google Scholar]

- Western, S. Eco-leadership: Towards the development of a new paradigm. In Leadership for Environmental Sustainability; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A.; Heller, D.; Mount, M.K. Five-factor model of personality and job satisfaction: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 530–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matzler, K.; Renzl, B. Personality Traits, Employee Satisfaction and Affective Commitment. Total Qual. Manag. 2007, 18, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 218 | 61.9 |

| Female | 134 | 38.1 |

| Age | ||

| 25–35 | 81 | 23 |

| 36–45 | 119 | 33.8 |

| 46–55 | 115 | 32.7 |

| 56–65 | 37 | 10.5 |

| Work experience | ||

| Under 1 year | 16 | 4.5 |

| 1 to under 4 years | 86 | 24.4 |

| 5 to under 9 years | 154 | 43.8 |

| 10 to under 15 years | 96 | 27.3 |

| Education level | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 195 | 55.4 |

| Master’s degree | 129 | 36.6 |

| PhD degree | 28 | 8.0 |

| Variables | M | SD | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Supervisor humility | 3.19 | 1.16 | 0.677 | 1 | |||

| 2 | Abusive supervision | 3.13 | 1.13 | 0.680 | −0.195 ** | 1 | ||

| 3 | Employee job satisfaction | 3.22 | 1.29 | 0.718 | 0.275 ** | −0.240 ** | 1 | |

| 4 | Employee creativity | 3.17 | 1.16 | 0.687 | 0.130 * | −0.110 * | 0.234 ** | 1 |

| CR values | 0.918 | 0.938 | 0.791 | 0.862 | ||||

| Path | Standardized Coefficient | T-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Effect | ||

| Supervisor Humility—Employee Job Satisfaction | 0.276 | 4.877 ** |

| Abusive Supervision—Employee Job Satisfaction | −0.202 | –3.620 ** |

| Employee Job Satisfaction—Employee Creativity | 0.269 | 4.662 ** |

| Age—Employee Creativity | 0.010 | 0.182 |

| Gender—Employee Creativity | −0.021 | −0.401 |

| Work Experience—Employee Creativity | 0.056 | 1.043 |

| Education Level—Employee Creativity | 0.030 | 0.556 |

| Indirect Effect | ||

| p-Value | Standardized Coefficient | |

| Supervisor Humility—Employee Job Satisfaction—Employee Creativity | 0.005 | 0.074 ** |

| Abusive Supervision—Employee Job Satisfaction—Employee Creativity | 0.003 | −0.054 ** |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miao, S.; Komil ugli Fayzullaev, A.; Dedahanov, A.T. Management Characteristics as Determinants of Employee Creativity: The Mediating Role of Employee Job Satisfaction. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1948. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su12051948

Miao S, Komil ugli Fayzullaev A, Dedahanov AT. Management Characteristics as Determinants of Employee Creativity: The Mediating Role of Employee Job Satisfaction. Sustainability. 2020; 12(5):1948. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su12051948

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiao, Siyuan, Abdulkhamid Komil ugli Fayzullaev, and Alisher Tohirovich Dedahanov. 2020. "Management Characteristics as Determinants of Employee Creativity: The Mediating Role of Employee Job Satisfaction" Sustainability 12, no. 5: 1948. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su12051948