Stakeholder Expectations of Future Policy Implementation Compared to Formal Policy Trajectories: Scenarios for Agricultural Food Systems in the Mekong Delta

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

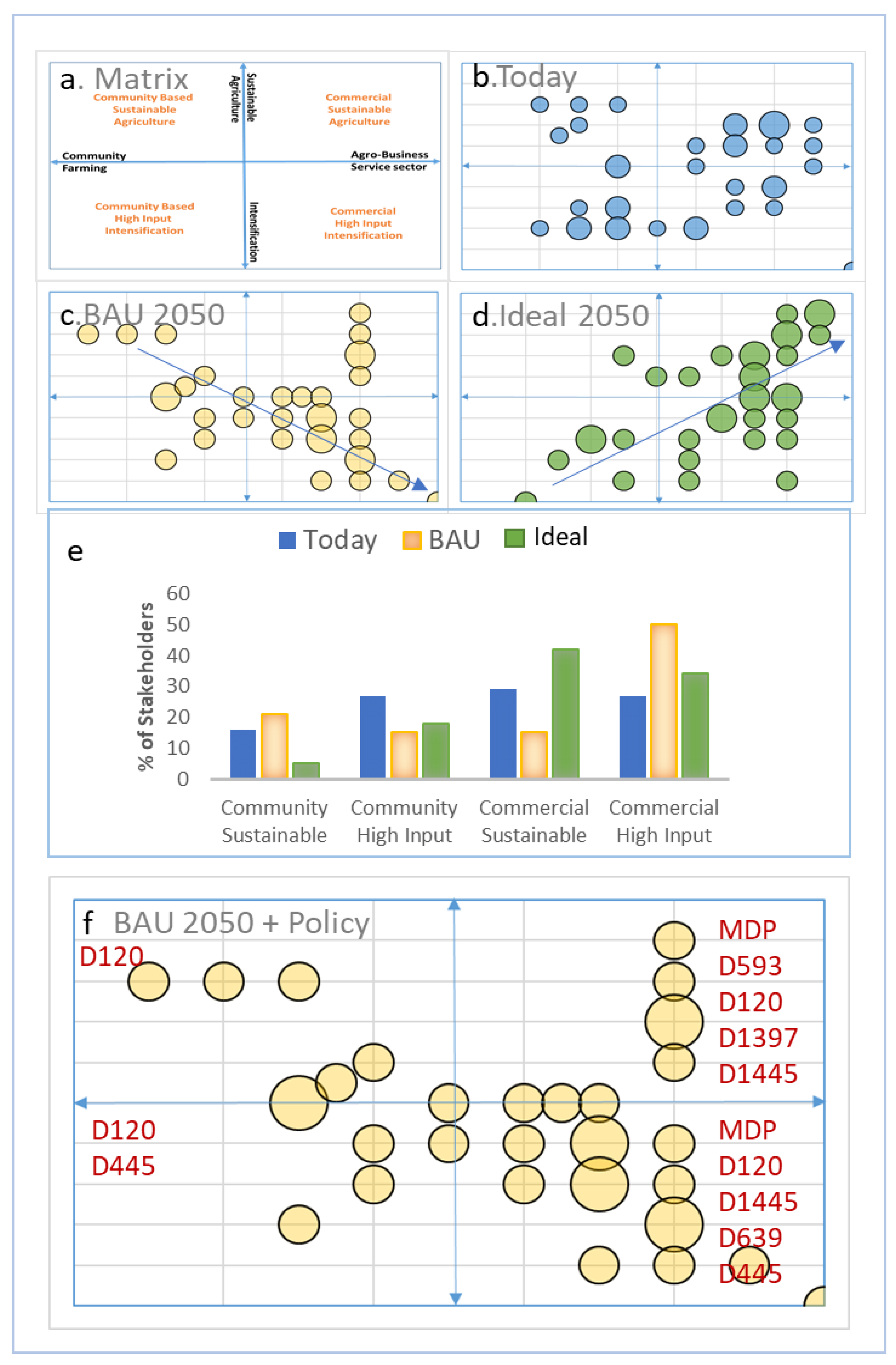

2.1. Building a Scenario Matrix

2.2. Development of Land Use Models for Each Scenario

2.3. Delta Level Stakeholder Workshop Methodology

- Which quadrant best describes the dominant approach to agriculture in the Mekong delta today?

- Where would you anticipate the dominant agricultural practice of the delta to be in 2050 if agricultural policy continues as it is trending currently? This is called the Business as Usual condition.

- Where would you anticipate the dominant agricultural practice of the delta to be in 2050 if agricultural policy is effectively and optimally implemented? This is called the Idealized condition.

3. Results from Stakeholder Workshop

Contextualizing Stakeholder Outputs in National and Regional Policy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Scenario 1: Community Sustainable Intensification

- (i.)

- great utilization of flood sediments for fertilization

- (ii.)

- greater exposure to floods with less engineering structures

- (iii.)

- more efficient use of water to reduce drought

- (iv.)

- soil management to reduce drought

- (i.)

- run by communes

- (ii.)

- lower overall yields

- (iii.)

- less income ($) in the first 20 years

- (iv.)

- lower-calorie food security but higher nutritional food security

- (v.)

- sustainable over a long period of time

- (vi.)

- less food waste

- (vii.)

- high-value crops, aquiculture, and livestock

- (viii.)

- uses traditional agricultural methods

- (ix.)

- low fertilizer through use of flood sediment and livestock

- (x.)

- climate and environmentally resilient

- (xi.)

- preserve and enhance mangrove as a coastal defense

- (xii.)

- high livelihood support and employment/possible reduced migration.

Scenario 2: Commercial Sustainable Intensification

- (i.)

- some utilization of flood sediments for fertilization

- (ii.)

- development of substantial engineering structures

- (iii.)

- limited soil and water conservation.

- (i.)

- run by agro-business-pressure to sell and aggregate land

- (ii.)

- same overall yields as current production

- (iii.)

- similar income as today ($) over the first 20 years, though declining fertility after that

- (iv.)

- same calorie food security, but potentially higher nutritional food security

- (v.)

- sustainable over a longer time, but progressive decline in soil health

- (vi.)

- less food waste hence intensification of output

- (vii.)

- higher diversity of high-value crops, but less than commune run

- (viii.)

- medium/high fertilizer use

- (ix.)

- some climate and environmentally resilient

- (x.)

- medium/high carbon release

- (xi.)

- preserve and enhance mangrove as a coastal defense

- (xii.)

- lower levels of livelihood support and higher migration

Scenario 3: Community High Input Intensification

- (i.)

- reasonable utilization of flood sediments for fertilization

- (ii.)

- development of some engineering structures

- (iii.)

- reasonably high soil and water conservation

- (iv.)

- run by commune and or cooperative

- (v.)

- similar overall yields as today

- (vi.)

- similar income ($) in the first 20 years, though possibly declining fertility after that

- (vii.)

- same calorie food security, but potentially higher nutritional food security

- (viii.)

- sustainable over a longer time, but progressive decline in soil health

- (ix.)

- less food waste hence intensification of output

- (x.)

- high diversity of high-value crops

- (xi.)

- medium fertilizer use

- (xii.)

- some climate and environmentally resilient

- (xiii.)

- medium levels of carbon release

- (xiv.)

- preserve and enhance mangrove as a coastal defense

- (xv.)

- similar levels of livelihood support and similar migration.

Scenario 4: Commercial High Input Intensification

- (i.)

- no utilization of flood sediments for fertilization

- (ii.)

- development of extensive further engineering structures

- (iii.)

- no soil & water conservation.

- (i.)

- run by agri-business with pressure to sell and aggregate land

- (ii.)

- very high income ($) in the first 15–20 years followed by a steep decline

- (iii.)

- profits removed from local area

- (iv.)

- high-calorie food security, but lower nutritional food security

- (v.)

- sustainable over a short/medium time only

- (vi.)

- typically high food waste, but could be decreased

- (vii.)

- high-value mono crops

- (viii.)

- uses large-scale technological practices, high efficiency agriculture

- (ix.)

- very high fertilizer use and intense livestock and aquiculture

- (x.)

- climate and environmentally low resilience, but operational in the short to medium term

- (xi.)

- engineered coastal defenses for rapid deployment of high intensity agriculture

- (xii.)

- low general livelihood support and employment with technical exceptions and increased migration.

Appendix B

Appendix C

References

- Nicholls, R.; Hutton, C.; Lázár, A.; Allan, A.; Adger, W.; Adams, H.; Wolf, J.; Rahman, M.; Salehin, M. Integrated assessment of social and environmental sustainability dynamics in the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna delta, Bangladesh. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2016, 183, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loos, J.; Abson, D.J.; Chappell, M.J.; Hanspach, J.; Mikulcak, F.; Tichit, M.; Fischer, J. Putting meaning back into “sustainable intensification”. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2014, 12, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafton, R.Q.; McLindin, M.; Hussey, K.; Wyrwoll, P.; Wichelns, D.; Ringler, C.; Garrick, D.; Pittock, J.; Wheeler, S.; Orr, S.; et al. Responding to Global Challenges in Food, Energy, Environment and Water: Risks and Options Assessment for Decision-Making. Asia Pac. Policy Stud. 2016, 3, 275–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hasan, S.; Evers, J.; Zegwaard, A.; Zwarteveen, M. Making waves in the Mekong Delta: Recognizing the work and the actors behind the transfer of Dutch delta planning expertise. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 62, 1583–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chapman, A.C.; Steven, D. Evaluating sustainable adaptation strategies for vulnerable mega-deltas using system dynamics modelling: Rice agriculture in the Mekong Delta’s an Giang Province, Vietnam. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 559, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chapman, A.D.; Stephen, E.; Hong Minh Hoang, D.; Emma, L.; Van Pham Dang Tri, T. Adaptation and development trade-offs: Fluvial sediment deposition and the sustainability of rice-cropping in an Giang Province, Me-kong Delta. Clim. Chang. 2016, 137, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hoang, L.P.; Biesbroek, R.; Tri, V.P.D.; Kummu, M.; Van Vliet, M.T.H.; Leemans, R.; Kabat, P.; Ludwig, F. Managing flood risks in the Mekong Delta: How to address emerging challenges under climate change and socioeconomic developments. Ambio 2018, 47, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chau, N.D.G.; Sebesvari, Z.; Amelung, W.; Renaud, F.G. Pesticide pollution of multiple drinking water sources in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam: Evidence from two provinces. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 9042–9058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, T.; Appleby, M.C.; Balmford, A.; Bateman, I.J.; Benton, T.G.; Bloomer, P.; Burlingame, B.; Dawkins, M.; Dolan, L.; Fraser, D.; et al. Sustainable Intensification in Agriculture: Premises and Policies. Science 2013, 341, 33–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahon, N.; Crute, I.; Simmons, E.; Islam, M.M. Sustainable intensification—“oxymoron” or “third-way”? A systematic review. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 74, 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beltran-Peña, A.; Rosa, L.; D’Odorico, P. Global food self-sufficiency in the 21st century under sustain-able intensification of agriculture. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 095004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoako Johnson, F.; Hutton, C.; Hornby, D.; Lazar, A.N.; Mukhopadhyay, A. Is shrimp farming a successful adaptation to salinity intrusion? A geospatial associative analysis of poverty in the populous Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna delta of Bangladesh. Sustain. Sci. 2016, 11, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lázár, A.N.; Clarke, D.; Adams, H.; Akanda, A.R.; Szabo, S.; Nicholls, R.J.; Matthews, Z.; Begum, D.; Saleh, A.F.M.; Abedin, M.A.; et al. Agricultural livelihoods in coastal Bangladesh under climate and environmental change—A model framework. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2015, 17, 1018–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aizen, M.A.; Aguiar, S.; Biesmeijer, J.C.; Garibaldi, L.A.; Inouye, D.W.; Jung, C.; Martins, D.J.; Medel, R.; Morales, C.L.; Ngo, H.; et al. Global agricultural productivity is threatened by increasing pollinator dependence without a parallel increase in crop diversification. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2019, 25, 3516–3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Global Green Growth Institute. Unleashing Green Growth in the Mekong Delta: A Multi-Stakeholder Approach to Identify Key Policy Options; Global Green Growth Institute: Seoul, Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Marcinko, C.; Nicholls, R.; Daw, T.; Hazra, S.; Hutton, C.; Hill, C.; Clarke, D.; Harfoot, A.; Basu, O.; Das, I.; et al. The Development of a Framework for the Integrated Assessment of SDG Trade-Offs in the Sundarban Biosphere Reserve. Water 2021, 13, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, A.; Darby, S. Dams and the economic value of sediment in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 32, 110–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trisyulianti, E.; Suryadi, K.; Prihantoro, B. A Conceptual Framework of Sustainability Balanced Scoce-card for State-Owned Plantation Enterprises. In Proceedings of the 2020 7th International Conference on Frontiers of Industrial Engineering (ICFIE), Singapore, 18–20 September 2020; pp. 62–66. [Google Scholar]

- Banson, K.E.; Nguyen, N.C.; Bosch, O.J.H.; Nguyen, T.V. A Systems Thinking Approach to Address the Complexity of Agribusiness for Sustainable Development in Africa: A Case Study in Ghana. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2014, 32, 672–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berchoux, T.; Watmough, G.R.; Amoako Johnson, F.; Hutton, C.W.; Atkinson, P.M. Collective influence of household and community capitals on agri-cultural employment as a measure of rural poverty in the Mahanadi Delta, India. Ambio 2020, 49, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ornetsmüller, C.; Verburg, P.; Heinimann, A. Scenarios of land system change in the Lao PDR: Transitions in re-sponse to alternative demands on goods and services provided by the land. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 75, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leinenkugel, P.; Kuenzer, C.; Oppelt, N.; Dech, S. Characterisation of land surface phenology and land cover based on moderate resolution satellite data in cloud prone areas—A novel product for the Mekong Basin. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 136, 180–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, A.S.; Nicholls, R.J.; Allan, A.; Arto, I.; Cazcarro, I.; Fernandes, J.A.; Hill, C.T.; Hutton, C.W.; Kay, S.; Lazar, A.N.; et al. Applying the global RCP–SSP–SPA scenario framework at sub-national scale: A multi-scale and participatory scenario approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 635, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, E.J.; Allan, A.; Salehin, M.; Caesar, J.; Nicholls, R.J.; Hutton, C.W. Integrating Science and Policy Through Stakeholder-Engaged Scenarios. In Ecosystem Services for Well-Being in Deltas; Nicholls, R., Hutton, C., Adger, W., Hanson, S., Rahman, M., Salehin, M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Vietnam. Socio-Economic Development Plan 2016–2020. 2016. Available online: http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/839361477533488479/Vietnam-SEDP-2016-2020.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2019).

- Seijger, C.W.; Douven, G.; van Halsema, L.; Hermans, J.; Evers, H.L.; Phi, M.F.; Khan, J.; Brunner, L.; Pols, W.; Ligtvoet, S.; et al. An analytical framework for strategic delta planning: Negotiating consent for long-term sustainable delta development. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2017, 60, 1485–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clausen, A.; Vu, H.H.; Pedrono, M. An evaluation of the environmental impact assessment system in Vietnam: The gap between theory and practice. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2011, 31, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.P.L. State-Society Interaction in Vietnam: The Everyday Dialogue of Local Irrigation Management in the Mekong Delta; Lit Verlag: Zürich, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, T.P.; Dieperink, C.; Otter, H.S.; Hoekstra, P. Governance conditions for adaptive freshwater management in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. J. Hydrol. 2018, 557, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.D.; Weger, J. Barriers to Implementing Irrigation and Drainage Policies in an Giang Province, Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Irrig. Drain. 2017, 67 (Suppl. 1), 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chartres, C.J.; Noble, A.D. Sustainable intensification: Overcoming land and water constraints on food production. Food Secur. 2015, 7, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; John, W.; Gretchen, D.; Andrew, N.; Nathanial, M.; Line, G.; Hanna, W.-S.; Fabrice, D.; Mihir, S.; Pasquale, S.; et al. Sustainable intensification of agriculture for human prosperity and global sustainability. Ambio 2017, 46, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Renaud, F.G.; Syvitski, J.P.; Sebesvari, Z.; E Werners, S.; Kremer, H.; Kuenzer, C.; Ramesh, R.; Jeuken, A.; Friedrich, J. Tipping from the Holocene to the Anthropocene: How threatened are major world deltas? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 5, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chukalla, A.D.; Reidsma, P.; Van Vliet, M.T.; Silva, J.V.; Van Ittersum, M.K.; Jomaa, S.; Rode, M.; Merbach, I.; Van Oel, P.R. Balancing indicators for sustainable intensification of crop production at field and river basin levels. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 705, 135925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanow, D. Conducting Interpretive Policy Analysis; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lejano, R.P. Frameworks for Policy Analysis: Merging Text and Context; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Vo, H.T.M.; Van Halsema, G.; Seijger, C.; Dang, N.K.; Dewulf, A.; Hellegers, P. Political agenda-setting for strategic delta planning in the Mekong Delta: Converging or diverging agendas of policy actors and the Mekong Delta Plan? J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 62, 1454–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hutton, C.W.; Hensengerth, O.; Berchoux, T.; Tri, V.P.D.; Tong, T.; Hung, N.; Voepel, H.; Darby, S.E.; Bui, D.; Bui, T.N.; et al. Stakeholder Expectations of Future Policy Implementation Compared to Formal Policy Trajectories: Scenarios for Agricultural Food Systems in the Mekong Delta. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5534. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su13105534

Hutton CW, Hensengerth O, Berchoux T, Tri VPD, Tong T, Hung N, Voepel H, Darby SE, Bui D, Bui TN, et al. Stakeholder Expectations of Future Policy Implementation Compared to Formal Policy Trajectories: Scenarios for Agricultural Food Systems in the Mekong Delta. Sustainability. 2021; 13(10):5534. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su13105534

Chicago/Turabian StyleHutton, Craig W., Oliver Hensengerth, Tristan Berchoux, Van P. D. Tri, Thi Tong, Nghia Hung, Hal Voepel, Stephen E. Darby, Duong Bui, Thi N. Bui, and et al. 2021. "Stakeholder Expectations of Future Policy Implementation Compared to Formal Policy Trajectories: Scenarios for Agricultural Food Systems in the Mekong Delta" Sustainability 13, no. 10: 5534. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su13105534