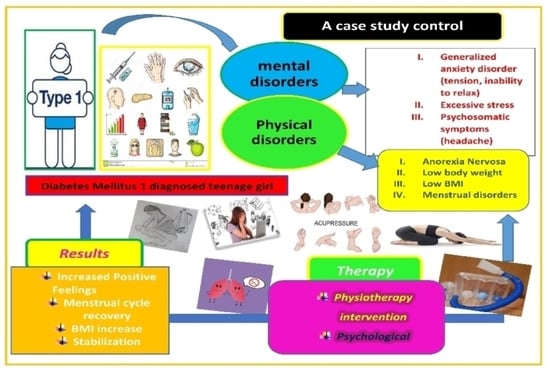

The Synergistic Effects of a Complementary Physiotherapeutic Scheme in the Psychological and Nutritional Treatment in a Teenage Girl with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus, Anxiety Disorder and Anorexia Nervosa

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Case-Study Report

2.1. Nutritional Assessment

2.2. Psychiatric Assessment

2.3. Physiotherapeutic Assessment

3. Therapy

3.1. Psychological Treatment

3.2. Medical Nutrition Therapy

3.3. Physiotherapy Intervention

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hessler, D.; Fisher, L.; Polonsky, W.; Johnson, N. Understanding the Areas and Correlates of Diabetes-Related Distress in Parents of Teens With Type 1 Diabetes. J. Pediatric Psychol. 2016, 41, 750–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Delamater, A.M.; de Wit, M.; McDarby, V.; Malik, J.A.; Hilliard, M.E.; Northam, E.; Acerini, C.L. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2018: Psychological care of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2018, 19, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delamater, A.M.; de Wit, M.; McDarby, V.; Malik, J.; Acerini, C.L. Psychological care of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2014, 15, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittemore, R.; Jaser, S.; Chao, A.; Jang, M.; Grey, M. Psychological Experience of Parents of Children With Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2012, 38, 562–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Edraki, M.; Rambod, M. Parental Resilience and Psychological Issues Psychological Predictors of Resilience in Parents of Insulin-Dependent Children and Adolescents; Shiraz University of Medical Sciences: Shiraz, Iran, 2018; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Yaribeygi, H.; Panahi, Y.; Sahraei, H.; Johnston, T.P.; Sahebkar, A. The impact of stress on body function: A review. EXCLI J. 2017, 16, 1057–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Faje, A.T.; Karim, L.; Taylor, A.; Lee, H.; Miller, K.K.; Mendes, N.; Meenaghan, E.; Goldstein, M.A.; Bouxsein, M.L.; Misra, M.; et al. Adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa have impaired cortical and trabecular microarchitecture and lower estimated bone strength at the distal radius. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 1923–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Powers, M.A.; Richter, S.; Ackard, D.; Gerken, S.; Meier, M.; Criego, A. Characteristics of persons with an eating disorder and type 1 diabetes and psychological comparisons with persons with an eating disorder and no diabetes. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2012, 45, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achamrah, N.; Coëffier, M.; Rimbert, A.; Charles, J.; Folope, V.; Petit, A.; Déchelotte, P.; Grigioni, S. Micronutrient Status in 153 Patients with Anorexia Nervosa. Nutrients 2017, 9, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanachi, M.; Dicembre, M.; Rives-Lange, C.; Ropers, J.; Bemer, P.; Zazzo, J.-F.; Poupon, J.; Dauvergne, A.; Melchior, J.-C. Micronutrients Deficiencies in 374 Severely Malnourished Anorexia Nervosa Inpatients. Nutrients 2019, 11, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Misra, M.; Klibanski, A. Endocrine consequences of anorexia nervosa. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014, 2, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singhal, V.; Misra, M.; Klibanski, A. Endocrinology of anorexia nervosa in young people. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2014, 21, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; ISBN 0-89042-555-8. [Google Scholar]

- Smink, F.R.E.; van Hoeken, D.; Oldehinkel, A.J.; Hoek, H.W. Prevalence and severity of DSM-5 eating disorders in a community cohort of adolescents. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2014, 47, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancuso, S.G.; Newton, J.R.; Bosanac, P.; Rossell, S.L.; Nesci, J.B.; Castle, D.J. Classification of eating disorders: Comparison of relative prevalence rates using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. Br. J. Psychiatry 2015, 206, 519–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gorwood, P.; Blanchet-Collet, C.; Chartrel, N.; Duclos, J.; Dechelotte, P.; Hanachi, M.; Fetissov, S.; Godart, N.; Melchior, J.-C.; Ramoz, N.; et al. New Insights in Anorexia Nervosa. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rikani, A.A.; Choudhry, Z.; Maqsood Choudhry, A.; Ikram, H.; Waheed Asghar, M.; Kajal, D.; Waheed, A.; Jahan Mobassarah, N. A critique of the literature on etiology of eating disorders. Ann. Neurosci. 2013, 20, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lock, J.; La Via, M.C. Practice Parameter for the Assessment and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Eating Disorders. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2015, 54, 412–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couturier, J.; Isserlin, L.; Norris, M.; Spettigue, W.; Brouwers, M.; Kimber, M.; McVey, G.; Webb, C.; Findlay, S.; Bhatnagar, N.; et al. Canadian practice guidelines for the treatment of children and adolescents with eating disorders. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairburn, C.G. Evidence-based treatment of anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2005, 37, S26–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolnes, L.-J. Embodying the body in anorexia nervosa--a physiotherapeutic approach. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2012, 16, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolnes, L.-J. Exercise and physical therapy help restore body and self in clients with severe anorexia nervosa. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2017, 21, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kolaitis, G.; Korpa, T.; Kolvin, I.; Tsiantis, J. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present episode (K-SADS-P): A pilot inter-rater reliability study for Greek children and adolescents. Eur. Psychiatry 2003, 18, 374–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psychountaki, M.; Zervas, Y.; Karteroliotis, K.; Spielberger, C. Reliability and validity of the Greek version of the STAIC. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2003, 19, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Healthcare and Excellence (NICE). Recommendations|Eating Disorders: Recognition and Treatment|Guidance|NICE [NG69]; NICE: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Junior MARSIPAN Group. Junior MARSIPAN: Management of Really Sick Patients under 18 with Anorexia Nervosa; Royal College of Psychiatrists: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hackert, A.N.; Kniskern, M.A.; Beasley, T.M. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Revised 2020 Standards of Practice and Standards of Professional Performance for Registered Dietitian Nutritionists (Competent, Proficient, and Expert) in Eating Disorders. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 120, 1902–1919.e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, S.; Marnane, C.; McMaster, C.; Thomas, A. Development of the “Recovery from Eating Disorders for Life” Food Guide (REAL Food Guide)–A food pyramid for adults with an eating disorder. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hanlan, M.E.; Griffith, J.; Patel, N.; Jaser, S.S. Eating Disorders and Disordered Eating in Type 1 Diabetes: Prevalence, Screening, and Treatment Options. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galli-Tsinopoulou, A.; Grammatikopoulou, M.G.; Stylianou, C.; Kokka, P.; Emmanouilidou, E. A preliminary case-control study on nutritional status, body composition, and glycemic control of Greek children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J. Diabetes 2009, 1, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaser, S.S.; Grey, M. A Pilot Study of Observed Parenting and Adjustment in Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes and their Mothers. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2010, 35, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cunningham, N.R.; Vesco, A.T.; Dolan, L.M.; Hood, K.K. From Caregiver Psychological Distress to Adolescent Glycemic Control: The Mediating Role of Perceived Burden around Diabetes Management. J. Pediatic. Psychol. 2011, 36, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ravi, S.; Forsberg, S.; Fitzpatrick, K.; Lock, J. Is There a Relationship Between Parental Self-Reported Psychopathology and Symptom Severity in Adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa? Eat. Disord. 2008, 17, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyke, J.; Matsen, J. Family functioning and risk factors for disordered eating. Eat. Behav. 2013, 14, 497–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappou, K.; Ntougia, M.; Kourtesi, A.; Panagouli, E.; Vlachopapadopoulou, E.; Michalacos, S.; Gonidakis, F.; Mastorakos, G.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Tsolia, M.; et al. Neuroimaging Findings in Adolescents and Young Adults with Anorexia Nervosa: A Systematic Review. Children 2021, 8, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorr, M.; Miller, K.K. The endocrine manifestations of anorexia nervosa: Mechanisms and management. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2017, 13, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, K.K. Endocrine Dysregulation in Anorexia Nervosa Update. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 2939–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, E.A.; Holsen, L.M.; DeSanti, R.; Santin, M.; Meenaghan, E.; Herzog, D.B.; Goldstein, J.M.; Klibanski, A. Increased hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal drive is associated with decreased appetite and hypoactivation of food-motivation neurocircuitry in anorexia nervosa. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2013, 169, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Connan, F.; Lightman, S.; Landau, S.; Wheeler, M.; Treasure, J.; Campbell, I. An investigation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis hyperactivity in anorexia nervosa: The role of CRH and AVP. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2007, 41, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, G.C.; Ferreira, M.L. Physiotherapy improves eating disorders and quality of life in bulimia and anorexia nervosa. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 1519–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandy, A.; Broadbridge, H. The role of physiotherapy in anorexia nervosa management. Br. J. Ther. Rehabil. 1998, 5, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, K. Physiotherapy in the Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa. Physiotherapy 1988, 74, 62–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, B.A.; Schenkman, M. Functional Recovery of a Patient With Anorexia Nervosa: Physical Therapist Management in the Acute Care Hospital Setting. Phys. Ther. 2012, 92, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Probst, M.; Majeweski, M.L.; Albertsen, M.N.; Catalan-Matamoros, D.; Danielsen, M.; De Herdt, A.; Duskova Zakova, H.; Fabricius, S.; Joern, C.; Kjölstad, G.; et al. Physiotherapy for patients with anorexia nervosa. Adv. Eat. Disord. 2013, 1, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, R.; Sousa, N.; Themudo-Barata, J.; Reis, V. Impact of a community-based exercise programme on physical fitness in middle-aged and older patients with type 2 diabetes. Gac. Sanit. 2016, 30, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- da Cunha Nascimento, D.; Alsamir Tibana, R.; Benik, F.; Fontana, K.E.; Ribeiro Neto, F.; Santos de Santana, F.; dos Santos Neto, L.; André Sousa Silva, R.; de Oliveira Silva, A.; Lopes de Farias, D.; et al. Sustained effect of resistance training on blood pressure and hand grip strength following a detraining period in elderly hypertensive women: A pilot study. Clin. Interv. Aging 2014, 9, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eyigor, S.; Karapolat, H.; Durmaz, B.; Ibisoglu, U.; Cakir, S. A randomized controlled trial of Turkish folklore dance on the physical performance, balance, depression and quality of life in older women. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2009, 48, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabkasorn, C.; Miyai, N.; Sootmongkol, A.; Junprasert, S.; Yamamoto, H.; Arita, M.; Miyashita, K. Effects of physical exercise on depression, neuroendocrine stress hormones and physiological fitness in adolescent females with depressive symptoms. Eur. J. Public Health 2006, 16, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; Rha, D.; Park, E.S. Change in Pulmonary Function after Incentive Spirometer Exercise in Children with Spastic Cerebral Palsy: A Randomized Controlled Study. Yonsei Med. J. 2016, 57, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Date (dd/mm/y) | Height (cm) | Body Weight (kg) | Age (yrs, mos) | BMI (kg/m2) | HbA1c (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior to treatment | |||||

| 01/09/2016 | 162.2 | 40.0 | 11 yrs, 11 mos | 15.2 | 14.0 |

| 06/12/2016 | 165.0 | 43.7 | 12 yrs, 3 mos | 16.1 | 5.8 |

| 21/03/2017 | 166.0 | 44.3 | 12 yrs, 5 mos | 16.1 | 6.4 |

| 13/06/2017 | 166.0 | 45.0 | 12 yrs, 8 mos | 16.3 | 6.9 |

| 10/10/2017 | 168.6 | 48.2 | 13 yrs, 0 mos | 16.9 | 6.8 |

| Start of treatment | |||||

| 11/01/2018 | 168.7 | 47.6 | 13 yrs, 3 mos | 16.7 | 6.8 |

| After treatment | |||||

| 28/03/2018 | 168.8 | 50.7 | 13 yrs, 6 mos | 17.8 | 6.9 |

| 27/04/2018 | 168.8 | 52.0 | 13 yrs, 7 mos | 19.3 | 6.5 |

| 06/07/2018 | 169.4 | 51.5 | 13 yrs, 8 mos | 18.0 | 6.3 |

| 09/10/2018 | 169.6 | 54.2 | 14 yrs, 0 mos | 18.9 | 6.7 |

| 18/12/2018 | 169.8 | 54.7 | 14 yrs, 2 mos | 19.0 | 6.2 |

| 31/01/2019 | 170.4 | 55.0 | 14 yrs, 4 mos | 18.9 | 6.3 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsakona, P.; Dafoulis, V.; Vamvakis, A.; Kosta, K.; Mina, S.; Kitsatis, I.; Hristara-Papadopoulou, A.; Roilides, E.; Tsiroukidou, K. The Synergistic Effects of a Complementary Physiotherapeutic Scheme in the Psychological and Nutritional Treatment in a Teenage Girl with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus, Anxiety Disorder and Anorexia Nervosa. Children 2021, 8, 443. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/children8060443

Tsakona P, Dafoulis V, Vamvakis A, Kosta K, Mina S, Kitsatis I, Hristara-Papadopoulou A, Roilides E, Tsiroukidou K. The Synergistic Effects of a Complementary Physiotherapeutic Scheme in the Psychological and Nutritional Treatment in a Teenage Girl with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus, Anxiety Disorder and Anorexia Nervosa. Children. 2021; 8(6):443. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/children8060443

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsakona, Pelagia, Vaios Dafoulis, Anastasios Vamvakis, Konstantina Kosta, Styliani Mina, Ioannis Kitsatis, Alexandra Hristara-Papadopoulou, Emmanuel Roilides, and Kyriaki Tsiroukidou. 2021. "The Synergistic Effects of a Complementary Physiotherapeutic Scheme in the Psychological and Nutritional Treatment in a Teenage Girl with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus, Anxiety Disorder and Anorexia Nervosa" Children 8, no. 6: 443. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/children8060443