Parental Socialization Styles: The Contribution of Paternal and Maternal Affect/Communication and Strictness to Family Socialization Style

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Parental Socialization Styles and their Dimensions

1.2. The Contribution of Parental Figures to the Establishment of Family Socialization Style

1.3. The Contribution of Parenting Dimensions to the Establishment of Family Socialization Style

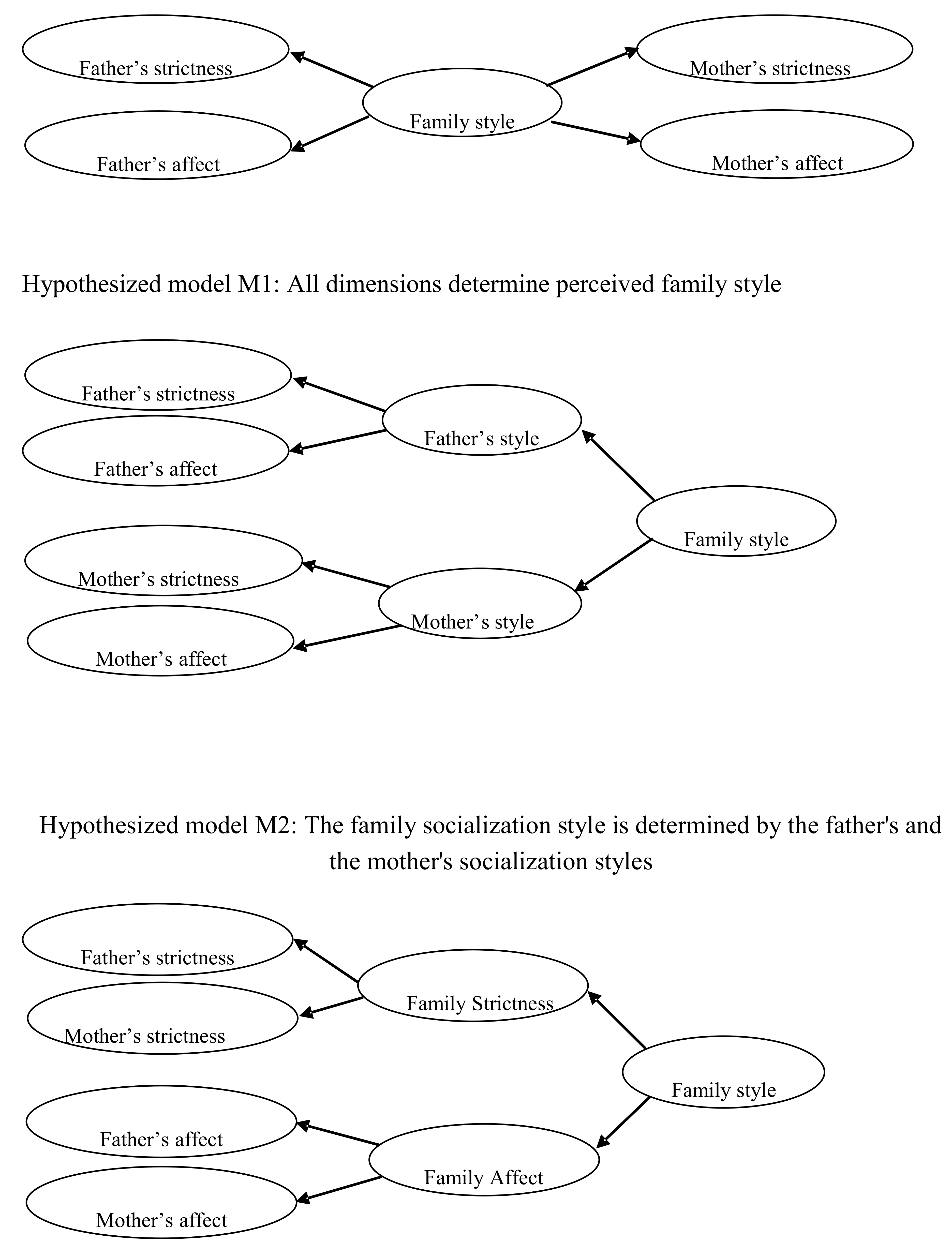

1.4. The Present Study

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Affect-Communication Dimension

2.2.2. Strictness Dimension

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Analysis

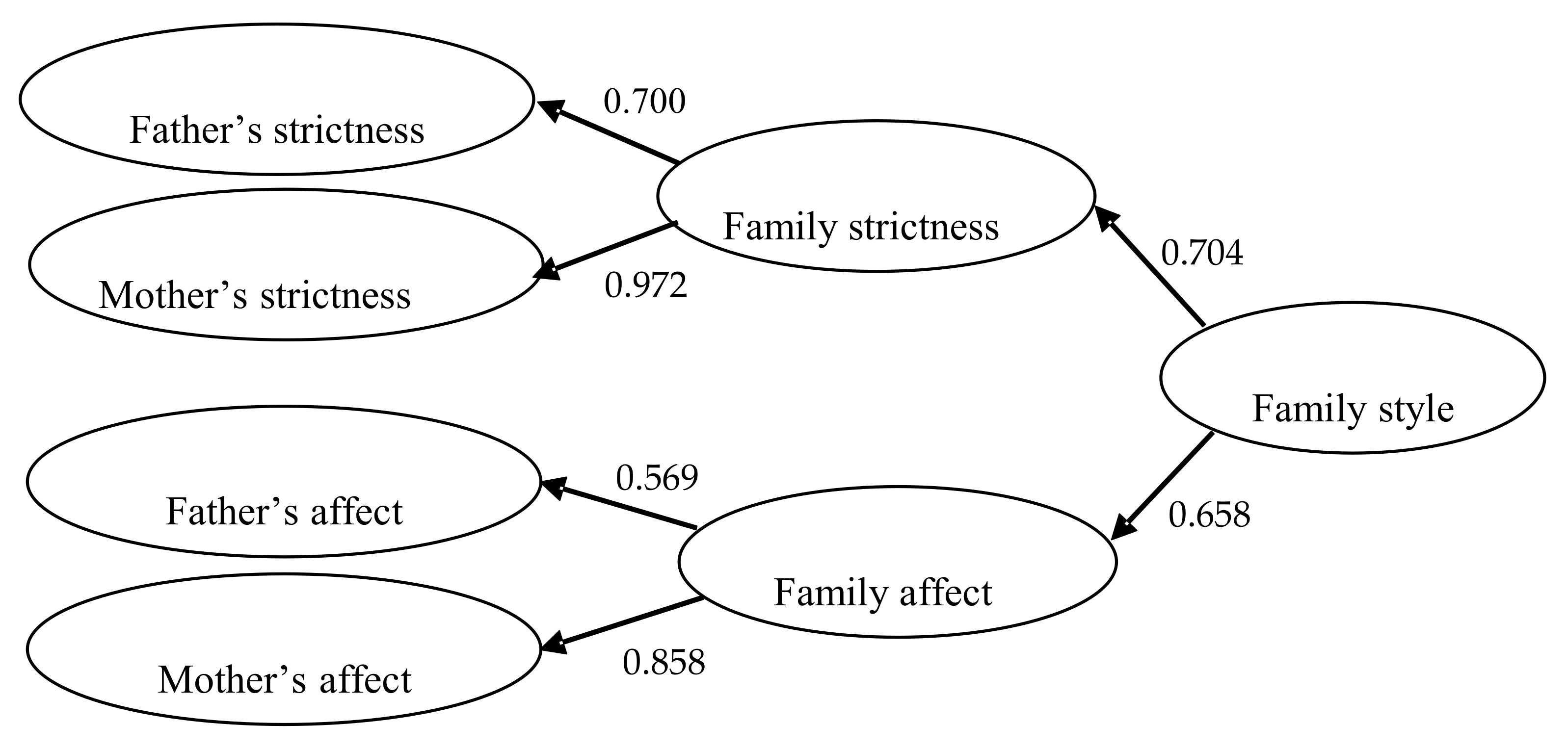

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fernández-García, C.-M.; Rodríguez-Menéndez, C.; Peña-Calvo, J.-V. Parental Control in Interpersonal Acceptance-Rejection Theory: A Study with a Spanish Sample Using Parents’ Version of Parental Acceptation-Rejection/Control Questionnaire. An. Psicol. 2017, 33, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendo-Lázaro, S.; León-del-Barco, B.; Polo-del-Río, M.-I.; Yuste-Tosina, R.; López-Ramos, V.-M. The Role of Parental Acceptance–Rejection in Emotional Instability during Adolescence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, O.; Serra, E. Raising Children with Poor School Performance: Parenting Styles and Short- and Long-Term Consequences for Adolescent and Adult Development. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, O.F.; Serra, E.; Zacarés, J.J.; García, F. Parenting Styles and Short- and Long-Term Socialization Outcomes: A Study among Spanish Adolescents and Older Adults. Psychosoc. Interv. 2018, 27, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livesey, C.M.W.; Rostain, A.L. Involving Parents/Family in Treatment during the Transition from Late Adolescence to Young Adulthood. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 26, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccoby, E.E. The Role of Parents in the Socialization of Children. Dev. Psychol. 1992, 28, 1006–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, L.J.; Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Christensen, K.J.; Evans, C.A.; Carroll, J.S. Parenting in Emerging Adulthood: An Examination of Parenting Clusters and Correlates. J. Youth Adolesc. 2011, 40, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.E.; Ciarrochi, J.; Heaven, P.C.L. Inflexible Parents, Inflexible Kids: A 6-Year Longitudinal Study of Parenting Style and the Development of Psychological Flexibility in Adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2012, 41, 1053–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumrind, D. Authoritative Parenting Revisited: History and Current Status. Authoritative Parent. Synth. Nurtur. Discip. Optim. Child Dev. 2013, 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccoby, E.E.; Martin, J.A. Socialization in the Context of the Family: Parent-Child Interaction. In Handbook of Child Psychology: Socialization, Personality, and Social Development; Hetherington, E.M., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1983; Volume 4, pp. 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, I.; Cruise, E.; García, Ó.F.; Murgui, S. English Validation of the Parental Socialization Scale—ESPA29. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, I.; Garcia, F.; Fuentes, M.C.; Veiga, F.; Garcia, O.F.; Rodrigues, Y.; Cruise, E.; Serra, E. Researching Parental Socialization Styles across Three Cultural Contexts: Scale ESPA29 Bi-Dimensional Validity in Spain, Portugal, and Brazil. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darling, N.; Steinberg, L. Parenting Style as Context: An Integrative Model. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 113, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L. Psychological Control: Style or Substance? New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2005, 2005, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, J.T.Y.; Shek, D.T.L. Unbroken Homes: Parenting Style and Adolescent Positive Development in Chinese Single-Mother Families Experiencing Economic Disadvantage. Child Indic. Res. 2018, 11, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Kubzansky, L.D.; VanderWeele, T.J. Parental Warmth and Flourishing in Mid-Life. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 220, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Meier, J. Father Love and Mother Love: Contributions of Parental Acceptance to Children’s Psychological Adjustment. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2017, 9, 459–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, I.; Scheffels, J. 15-Year-Old Tobacco and Alcohol Abstainers in a Drier Generation: Characteristics and Lifestyle Factors in a Norwegian Cross-Sectional Sample. Scand. J. Public Health 2018, 4, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaleque, A.; Ali, S. A Systematic Review of Meta-Analyses of Research on Interpersonal Acceptance–Rejection Theory: Constructs and Measures. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2017, 9, 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohner, R.P.; Lansford, J.E. Deep Structure of the Human Affectional System: Introduction to Interpersonal Acceptance-Rejection Theory. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2017, 9, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-del-Barco, B.; Fajardo-Bullón, F.; Mendo-Lázaro, S.; Rasskin-Gutman, I.; Iglesias-Gallego, D. Impact of the Familiar Environment in 11–14-Year-Old Minors’ Mental Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaureguizar, J.; Bernaras, E.; Bully, P.; Garaigordobil, M. Perceived Parenting and Adolescents’ Adjustment. Psicol. Reflex. Crit. 2018, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.A.; Godás, A.; Ferraces, M.J.; Lorenzo, M. Academic Performance of Native and Immigrant Students: A Study Focused on the Perception of Family Support and Control, School Satisfaction, and Learning Environment. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gargurevich, R.; Soenens, B. Psychologically Controlling Parenting and Personality Vulnerability to Depression: A Study in Peruvian Late Adolescents. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansford, J.E.; Laird, R.D.; Pettit, G.S.; Bates, J.E.; Dodge, K.A. Mothers’ and Fathers’ Autonomy-Relevant Parenting: Longitudinal Links with Adolescents’ Externalizing and Internalizing Behavior. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 1877–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arim, R.G.; Marshall, S.K.; Shapka, J.D. A Domain-Specific Approach to Adolescent Reporting of Parental Control. J. Adolesc. 2010, 33, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laible, D.J.; Carlo, G. The Differential Relations of Maternal and Paternal Support and Control to Adolescent Social Competence, Self-Worth, and Sympathy. J. Adolesc. Res. 2004, 19, 759–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steinberg, L.; Blatt-Eisengart, I.; Cauffman, E. Patterns of Competence and Adjustment among Adolescents from Authoritative, Authoritarian, Indulgent, and Neglectful Homes: A Replication in a Sample of Serious Juvenile Offenders. J. Res. Adolesc. 2006, 16, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, I.; Murgui, S.; Garcia, O.F.; Garcia, F. Parenting in the Digital Era: Protective and Risk Parenting Styles for Traditional Bullying and Cyberbullying Victimization. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 90, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, R.K. Beyond Parental Control and Authoritarian Parenting Style: Understanding Chinese Parenting Through the Cultural Notion of Training. Child Dev. 1994, 65, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamborn, S.D.; Mounts, N.S.; Steinberg, L.; Dornbusch, S.M. Patterns of Competence and Adjustment among Adolescents from Authoritative, Authoritarian, Indulgent, and Neglectful Families. Child Dev. 1991, 62, 1049–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aymerich, M.; Musitu, G.; Palmero, F. Family Socialisation Styles and Hostility in the Adolescent Population. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L. We Know Some Things: Parent–Adolescent Relationships in Retrospect and Prospect. J. Res. Adolesc. 2001, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppens, S.; Ceulemans, E. Parenting Styles: A Closer Look at a Well-Known Concept. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva, A.; Parra, Á.; Arranz, E. Estilos Relacionales Parentales y Ajuste Adolescente. Infanc. Aprendiz. 2008, 31, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares, M.C.G.; Fernández, M.V.C.; Rusillo, M.T.C.; Arias, P.F.C. Emotional Intelligence Profiles in College Students and Their Fathers’ and Mothers’ Parenting Practices. J. Adult Dev. 2018, 25, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrebola, I.A.; González-Gijón, G.; Garzón, F.R.; Gómez, M.D.M.O. La Percepción de Los Adolescentes de Las Prácticas Parentales Desde La Perspectiva de Género. Pedagog. Soc. Rev. Interuniv. 2019, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, C.; Renk, K. Differential Parenting between Mothers and Fathers: Implications for Late Adolescents. J. Fam. Issues 2008, 29, 806–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phares, V.; Fields, S.; Kamboukos, D. Fathers’ and Mothers’ Involvement with Their Adolescents. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2009, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bat Or, M.B.; Papadaki, A.; Shalev, O.; Kourkoutas, E. Associations between Perception of Parental Behavior and “Person Picking an Apple From a Tree” Drawings among Children with and without Special Educational Needs (SEN). Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Khaleque, A.; Rohner, R.P. Influence of Perceived Teacher Acceptance and Parental Acceptance on Youth’s Psychological Adjustment and School Conduct: A Cross-Cultural Meta-Analysis. Cross Cult. Res. 2015, 49, 204–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleque, A.; Rohner, R.P. Transnational Relations between Perceived Parental Acceptance and Personality Dispositions of Children and Adults. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 16, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastaits, K.; Ponnet, K.; Mortelmans, D. Parenting of Divorced Fathers and the Association with Children’s Self-Esteem. J. Youth Adolesc. 2012, 41, 1643–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Baya, D.; Mendoza, R.; Camacho, I.; de Matos, M.G. Latent Growth Curve Model of Perceived Family Relationship Quality and Depressive Symptoms during Middle Adolescence in Spain. J. Fam. Issues 2018, 39, 2037–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raboteg-Saric, Z.; Sakic, M. Relations of Parenting Styles and Friendship Quality to Self-Esteem, Life Satisfaction and Happiness in Adolescents. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2014, 9, 749–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Khatun, N.; Khaleque, A.; Rohner, R.P. They Love Me Not: A Meta-Analysis of Relations between Parental Undifferentiated Rejection and Offspring’s Psychological Maladjustment. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2019, 50, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, O.F.; Lopez-Fernandez, O.; Serra, E. Raising Spanish Children with an Antisocial Tendency: Do We Know What the Optimal Parenting Style Is? J. Interpers. Violence 2018, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riquelme, M.; Garcia, O.F.; Serra, E. Desajuste Psicosocial en La Adolescencia: Socialización Parental, Autoestima y Uso de Sustancias. An. Psicol. 2018, 34, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Ruiz, D.; Estévez, E.; Jiménez, T.I.; Murgui, S. Parenting Style and Reactive and Proactive Adolescent Violence: Evidence from Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braza, P.; Carreras, R.; Muñoz, J.M.; Braza, F.; Azurmendi, A.; Pascual-Sagastizábal, E.; Cardas, J.; Sánchez-Martín, J.R. Negative Maternal and Paternal Parenting Styles as Predictors of Children’s Behavioral Problems: Moderating Effects of the Child’s Sex. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares, M.-C.G.; De la Torre Cruz, M.-J.; De la Villa Carpio, M.; Rusillo, M.-T.C.; Casanova Arias, P.-F. Consistency/Inconsistency in Paternal and Maternal Parenting Styles and Daily Stress in Adolescence//Consistencia/Inconsistencia en Los Estilos Educativos de Padres y Madres, y Estrés Cotidiano en La Adolescencia. Rev. Psicodidact. 2014, 19, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, L.G.; Conger, R.D. Linking Mother–Father Differences in Parenting Parenting Styles and Adolescent Outcomes. J. Fam. Issues 2007, 28, 212–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.C.; Affuso, G.; Esposito, C.; Bacchini, D. Parental Acceptance–Rejection and Adolescent Maladjustment: Mothers’ and Fathers’ Combined Roles. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 1352–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwairy, M.A. Parental Inconsistency Versus Parental Authoritarianism: Associations with Symptoms of Psychological Disorders. J. Youth Adolesc. 2008, 37, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, E.; Gámez-Guadix, M.; Orue, I. El Inventario de Dimensiones de Disciplina (DDI), Versión Niños y Adolescentes: Estudio de Las Prácticas de Disciplina Parental Desde Una Perspectiva de Género. An. Psicol. 2010, 26, 410–418. [Google Scholar]

- Casais Molina, D.; Flores Galaz, M.; Domínguez Espinosa, A. Percepción de Prácticas de Crianza: Análisis Confirmatorio de Una Escala Para Adolescentes. Acta Investig. Psicol. 2017, 7, 2717–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tur-Porcar, A.; Mestre, V.; Samper, P.; Malonda, E. Crianza y Agresividad de Los Menores: ¿es Diferente La Influencia Del Padre y de La Madre? Psicothema 2012, 24, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Murray, K.W.; Dwyer, K.M.; Rubin, K.H.; Knighton-Wisor, S.; Booth-LaForce, C. Parent-Child Relationships, Parental Psychological Control, and Aggression: Maternal and Paternal Relationships. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 1361–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnick, D.L.; Bornstein, M.H.; Lansford, J.E.; Malone, P.S.; Pastorelli, C.; Skinner, A.T.; Sorbring, E.; Tapanya, S.; Uribe Tirado, L.M.; Zelli, A.; et al. Perceived Mother and Father Acceptance-Rejection Predict Four Unique Aspects of Child Adjustment across Nine Countries. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2015, 56, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.R.; Wang, C.; Li, W.; Wilson, S.; Bush, K.R.; Peterson, G. Chinese Parenting Behaviors, Adolescent School Adjustment, and Problem Behavior. Marriage Fam. Rev. 2015, 51, 489–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.; Sireno, S.; Larcan, R.; Cuzzocrea, F. The Six Dimensions of Parenting and Adolescent Psychological Adjustment: The Mediating Role of Psychological Needs. Scand. J. Psychol. 2018, 60, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersabé, R.; Fuentes, M.J.; Motrico, E. Análisis Psicométrico de Dos Escalas Para Evaluar Estilos Educativos Parentales. Psicothema 2001, 13, 678–684. [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt, L. Change-Oriented Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: The Direct and Moderating Influence of Goal Orientation. J. Retail. 2004, 80, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 6th ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M. EQS Structural Equations Program Manual; Multivariate Software: Encino, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Satorra, A.; Bentler, P.M. A Scaled Difference Chi-Square Test Statistic for Moment Structure Analysis. Psychometrika 2001, 66, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS, EQS, and LISREL: Comparative Approaches to Testing for the Factorial Validity of a Measuring Instrument. Int. J. Test. 2001, 1, 55–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleque, A.; Rohner, R.P. Pancultural Associations between Perceived Parental Acceptance and Psychological Adjustment of Children and Adults: A Meta-Analytic Review of Worldwide Research. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2012, 43, 784–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Del-Barco, B.; Mendo-Lázaro, S.; Polo-Del-Río, M.I.; López-Ramos, V.M. Parental Psychological Control and Emotional and Behavioral Disorders among Spanish Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ortiz, O.; Romera, E.; Ortega-Ruiz, R.; Del Rey, R. Parenting Practices as Risk or Preventive Factors for Adolescent Involvement in Cyberbullying: Contribution of Children and Parent Gender. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, M.; Padilla, S.; Máiquez, M.A.L. Home and Group-Based Implementation of the “Growing Up Happily in the Family” Program in at-Risk Psychosocial Contexts. Psychosoc. Interv. 2016, 25, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Relinque, C.; del Moral Arroyo, G.; León-Moreno, C.; Callejas Jerónimo, J.E. Child-to-Parent Violence: Which Parenting Style Is More Protective? A Study with Spanish Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calafat, A.; García, F.; Juan, M.; Becoña, E.; Fernández-Hermida, J.R. Which Parenting Style Is More Protective against Adolescent Substance Use? Evidence within the European Context. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014, 138, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes, M.J.; Motrico, E.; Bersabé, R.M. Estrategias de Socialización de Los Padres y Conflictos Entre Padres e Hijos En La Adolescencia. Anu. Psicol. 2003, 34, 385–400. [Google Scholar]

- Gartzia, L.; Aritzeta, A.; Balluerka, N.; Heredia, E.B. Inteligencia Emocional y Género: Más Allá de Las Diferencias Sexuales. An. Psicol. 2012, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, S. Las Contradicciones Culturales de La Maternidad; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Boudreault-Bouchard, A.M.; Dion, J.; Hains, J.; Vandermeerschen, J.; Laberge, L.; Perron, M. Impact of Parental Emotional Support and Coercive Control on Adolescents’ Self-Esteem and Psychological Distress: Results of a Four-Year Longitudinal Study. J. Adolesc. 2013, 36, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostain, A.L. 2.2 Involving Parents and Family in Treatment during the Transition from Late Adolescence to Young Adulthood. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 57, S3–S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Uclés, I.; González-Calderón, M.J.; del Barrio-Gándara, V.; Carrasco, M.Á. Perceived Parental Acceptance-Rejection and Children’s Psychological Adjustment: The Moderating Effects of Sex and Age. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 1336–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M. Associations of Parenting Dimensions and Styles with Externalizing Problems of Children and Adolescents: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 53, 873–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen-Bouck, L.; Patterson, M.M.; Chen, J. Relations of Collectivism Socialization Goals and Training Beliefs to Chinese Parenting. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2019, 50, 396–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Khaleque, A.; Rohner, R.P. Pancultural Gender Differences in the Relation between Perceived Parental Acceptance and Psychological Adjustment of Children and Adult Offspring: A Meta-Analytic Review of Worldwide Research. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2015, 46, 1059–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, A.C.; Steinberg, L.; Sellers, E.B. Adolescents’ Well-Being as a Function of Perceived Interparental Consistency. J. Marriage Fam. 1999, 61, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumrind, D. The Influence of Parenting Style on Adolescent Problem. J. Early Adolesc. 1991, 11, 56–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavassolie, T.; Dudding, S.; Madigan, A.L.; Thorvardarson, E.; Winsler, A. Differences in Perceived Parenting Style between Mothers and Fathers: Implications for Child Outcomes and Marital Conflict. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 2055–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korelitz, K.E.; Garber, J. Congruence of Parents’ and Children’s Perceptions of Parenting: A Meta-Analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 1973–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, E.S. Children’s Reports of Parental Behavior: An Inventory. Child Dev. 1965, 36, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, B.K. Parental Psychological Control: Revisiting a Neglected Construct. Child Dev. 1996, 67, 3296–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastaits, K.; Mortelmans, D. Does the Parenting of Divorced Mothers and Fathers Affect Children’s Well-Being in the Same Way? Child Indic. Res. 2014, 7, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastaits, K.; Ponnet, K.; Mortelmans, D. Do Divorced Fathers Matter? The Impact of Parenting Styles of Divorced Fathers on the Well-Being of the Child. J. Divorce Remarriage 2014, 55, 363–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babore, A.; Trumello, C.; Candelori, C.; Paciello, M.; Cerniglia, L. Depressive Symptoms, Self-Esteem and Perceived Parent–Child Relationship in Early Adolescence. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimino, S.; Cerniglia, L.; Paciello, M. Mothers with Depression, Anxiety or Eating Disorders: Outcomes on Their Children and the Role of Paternal Psychological Profiles. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2015, 46, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, M.E.A.; Altafim, E.R.P.; Linhares, M.B.M. Programa ACT Educando a Niños en Ambientes Seguros Para Promover Prácticas Educativas Maternas Positivas en Distintos Contextos Socioeconómicos. Psychosoc. Interv. 2017, 26, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | X2 (df) | p | X2/df | CFI | NFI | NNFI | IFI | RMSEA (90% CI) | AIC | CAIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 854.53 (332) | 0.000 | 2.57 | 0.894 | 0.839 | 0.880 | 0.895 | 0.060 (0.055–0.065) | 190.533 | −1504.999 |

| M2 | 765.72 (330) | 0.000 | 2.32 | 0.912 | 0.856 | 0.900 | 0.913 | 0.054 (0.049–0.059) | 105.728 | −1579.590 |

| M3 | 668.51 (330) | 0.000 | 2.02 | 0.932 | 0.894 | 0.922 | 0.932 | 0.048 (0.043–0.053) | 8.515 | −1676.802 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Axpe, I.; Rodríguez-Fernández, A.; Goñi, E.; Antonio-Agirre, I. Parental Socialization Styles: The Contribution of Paternal and Maternal Affect/Communication and Strictness to Family Socialization Style. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2204. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph16122204

Axpe I, Rodríguez-Fernández A, Goñi E, Antonio-Agirre I. Parental Socialization Styles: The Contribution of Paternal and Maternal Affect/Communication and Strictness to Family Socialization Style. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(12):2204. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph16122204

Chicago/Turabian StyleAxpe, Inge, Arantzazu Rodríguez-Fernández, Eider Goñi, and Iratxe Antonio-Agirre. 2019. "Parental Socialization Styles: The Contribution of Paternal and Maternal Affect/Communication and Strictness to Family Socialization Style" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 12: 2204. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph16122204