New Ways of Working? A Rapid Exploration of Emerging Evidence Regarding the Care of Older People during COVID19

Abstract

:1. Introduction

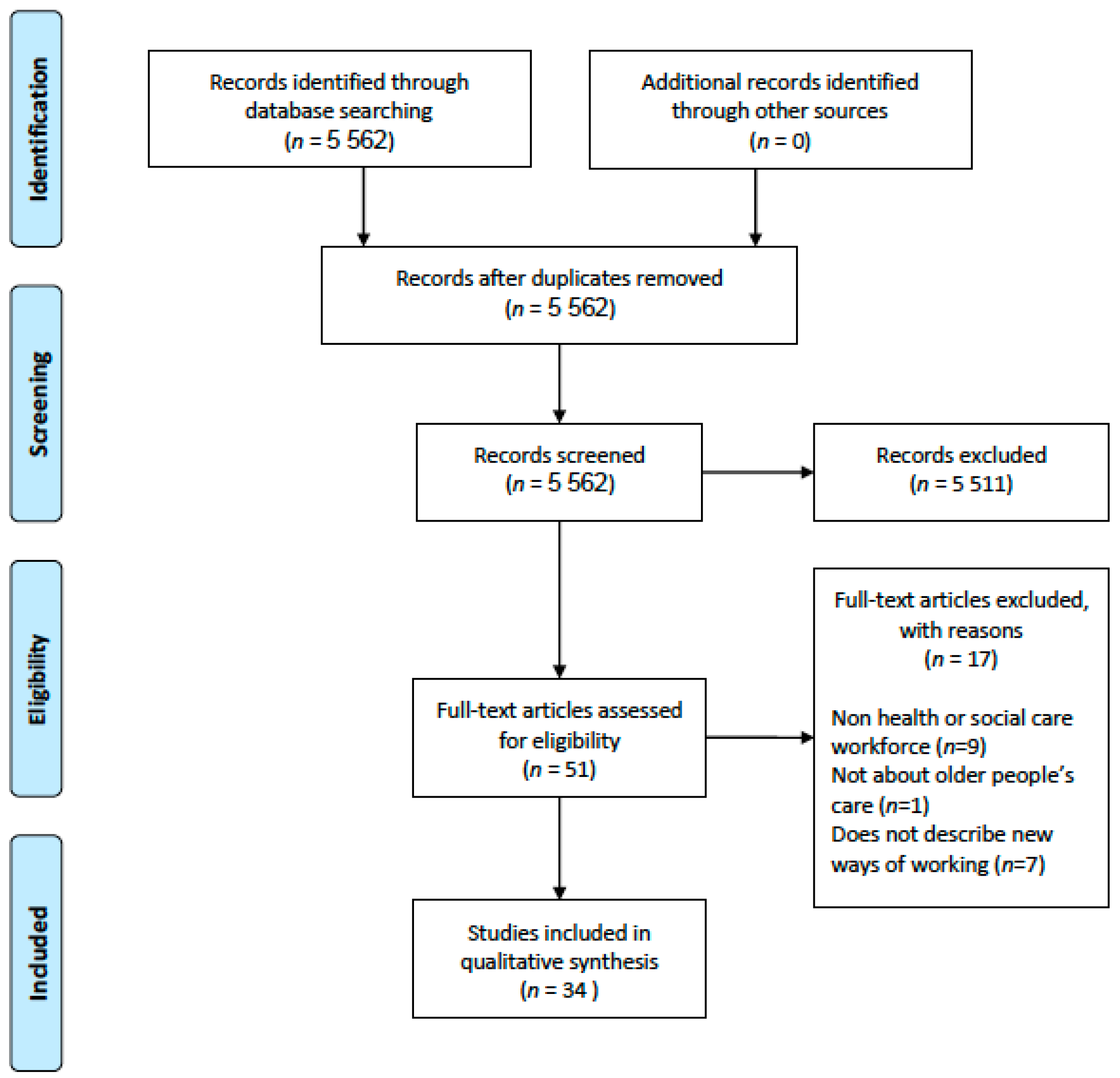

2. Methods

2.1. Identifying the Research Focus

2.2. Identifying Databases

2.2.1. Breadth

2.2.2. Depth

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Screening and Extraction

2.5. Validation

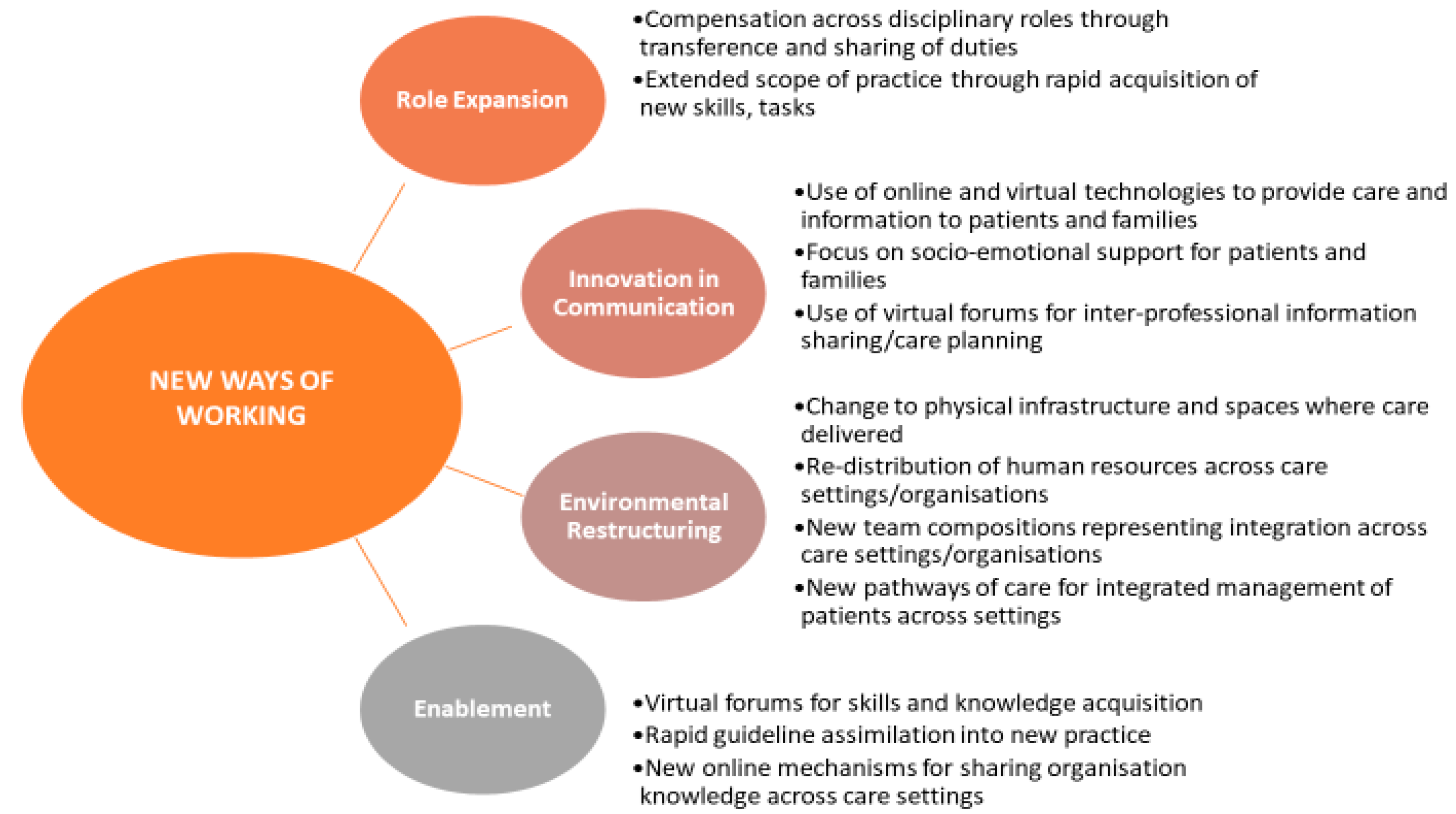

3. Results

3.1. Twitter: New Ways of Working in Health and Social Care during COVID-19

- Using telehealth and or phone consultations to provide ongoing care to patients

- Interprofessional work

- Team meetings using online platforms

- Trust and collaboration within teams

- Sharing information and a clear feedback loop between teams

- Teams felt empowered to change at a local level

3.2. Newspaper Articles: A focus on New Ways of Working in the Care of Older People during COVID-19

3.3. Validation Workshop

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Responding to Community Spread of COVID-19: Interim Guidance 2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Covid-19 Situation Worldwide, as of 19 August 2020. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/cases-2019-ncov-eueea (accessed on 19 August 2020).

- Lai, C.-C.; Shih, T.-P.; Ko, W.-C.; Tang, H.-J.; Hsueh, P.-R. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): The epidemic and the challenges. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.G.; Walls, R.M. Supporting the Health Care Workforce during the COVID-19 Global Epidemic. JAMA 2020, 323, 1439–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patel, P.D.; Cobb, J.; Wright, D.; Turer, R.W.; Jordan, T.; Humphrey, A.; Kepner, A.L.; Smith, G.; Rosenbloom, S.T. Rapid development of telehealth capabilities within pediatric patient portal infrastructure for COVID-19 care: Barriers, solutions, results. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2020, 27, 1116–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legido-Quigley, H.; Asgari, N.; Teo, Y.Y.; Leung, G.M.; Oshitani, H.; Fukuda, K.; Cook, A.R.; Hsu, L.Y.; Shibuya, K.; Heymann, D. Are high-performing health systems resilient against the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet 2020, 395, 848–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Onder, G.; Rezza, G.; Brusaferro, S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA 2020, 323, 1775–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lithander, F.; Neumann, S.; Tenison, E.; Lloyd, K.; Welsh, T.J.; Rodrigues, J.; Higgins, J.; Scourfield, L.; Christensen, H.; Haunton, V.; et al. COVID-19 in older people: A rapid clinical review. Age Ageing 2020, 49, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hanlon, S.; Inouye, S. Delirium: A missing piece in the COVID-19 pandemic puzzle. Age Ageing 2020, 49, 497–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Gou, X.; Pu, K.; Chen, Z.F.; Guo, Q.; Ji, R.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y. Prevalence of comorbidities in the novel Wuhan coronavirus (COVID-19) infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 94, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, K.; O’Neill, A.; Conneely, M.; Morrissey, A.; Leahy, S.; Meskell, P.; Pettigrew, J.; Galvin, R. Exploring the beliefs and experiences of older Irish adults and family carers during the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: A qualitative study protocol. HRB Open Res. 2020, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nurchis, M.C.; Pascucci, D.; Sapienza, M.; Villani, L.; D’Ambrosio, F.; Castrini, F.; Specchia, M.L.; Laurenti, P.; Damiani, G. Impact of the Burden of COVID-19 in Italy: Results of Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) and Productivity Loss. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health. Letter from CMO to Minister for Health re COVID-19 (Coronavirus)—27 March 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/en/collection/691330-national-public-health-emergency-team-covid-19-coronavirus/#minutes-from-meetings-in-march (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Government of Ireland. Latest Updates on COVID-19. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/en/news/7e0924-latest-updates-on-covid-19-coronavirus/ (accessed on 19 August 2020).

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R.; et al. Factors Associated with Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tannenbaum, S.I.; Traylor, A.M.; Thomas, E.J.; Salas, E. Managing teamwork in the face of pandemic: Evidence-based tips. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2020, 0, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, A.J.; Morley, E.J.; Henry, M.C. Staying ahead of the wave. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wensing, M.; Sales, A.; Armstrong, R.; Wilson, P. Implementation science in times of Covid-19. Implement. Sci. 2020, 15, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjara, S.G.; Shé Éidín, N.; O’Shea, M.; O’Donoghue, G.; Donnelly, S.; Brennan, J.; Whitty, H.; Maloney, P.; Claffey, A.; Quinn, S.; et al. Embedding collective leadership to foster collaborative inter-professional working in the care of older people (ECLECTIC). Study Protocol. HRB Open Res. 2020, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Munn, Z.; Stern, C.; Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Jordan, Z. What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. Theory Pract. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Connor, A.; Jackson, L.; Goldsmith, L.; Skirton, H. Can I get a retweetplease? Health research recruitment and the Twittersphere. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twitter. About Us. Available online: https://about.twitter.com/en_us/company.html (accessed on 18 June 2020).

- Hays, R.; Daker-White, G. The care data consensus? A qualitative analysis of opinions expressed on Twitter. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, F.; Dobermann, T.; Cave, J.A.K.; Thorogood, M.; Johnson, S.; Salamatian, K.; Goudge, J. The Impact of Online Social Networks on Health and Health Systems: A Scoping Review and Case Studies. Policy Internet 2015, 7, 473–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ní Shé, É.; Keogan, F.; McAuliffe, E.; O’Shea, D.; McCarthy, M.; McNamara, R.; Cooney, M.T. Undertaking a Collaborative Rapid Realist Review to Investigate What Works in the Successful Implementation of a Frail Older Person’s Pathway. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mwendwa, P.; Kroll, T.; De Brún, A. “To stop #FGM it is important to involve the owners of the tradition aka men”: An Exploratory Analysis of Social Media Discussions on Female Genital Mutilation. J. Afr. Interdiscip. Stud. 2020, 4, 34–47. [Google Scholar]

- Salzmann-Erikson, M. Virtual communication about psychiatric intensive care units: Social actor representatives claim space on Twitter. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 26, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillywhite, A.; Wolbring, G. Coverage of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning within Academic Literature, Canadian Newspapers, and Twitter Tweets: The Case of Disabled People. Societies 2020, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ní Shé, É.; O’Donnell, D.; Donnelly, S.; Davies, C.; Fattori, F.; Kroll, T. “What Bothers Me Most Is the Disparity between the Choices that People Have or Don’t Have”: A Qualitative Study on the Health Systems Responsiveness to Implementing the Assisted Decision-Making (Capacity) Act in Ireland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, M.A.; Goniu, N.; Moreno, P.S.; Diekema, D. Ethics of social media research: Common concerns and practical considerations. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2013, 16, 708–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bufton, J. A day in the life of a home carer in Worcestershire during coronavirus pandemic. Malvern Gazette, 17 April 2020; 1. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, P. Care home workers on battle they face to keep residents safe; ‘We Have No Idea What Environment We are Going Into’. Grimsby Telegraph, 15 April 2020; 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anon. ‘Care home workers’ week-long live-ins with residents in coronavirus lockdown. Eastern Daily Press, 15 April 2020; 4. [Google Scholar]

- Anon. Meet NHS staff using skills to help in frontline; They’ve Stepped Away from Current Roles. Leicester Mercury, 1 May 2020; 6. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham, J. Undervalued care workers continue to show just how vital they are in fight against coronavirus; Hard working and selfless carers are the unsung heroes of this crisis. Liverpool Echo, 13 April 2020; 7. [Google Scholar]

- Youle, R. How work has changed for carers during health crisis. South Wales Echo, 18 April 2020; 9. [Google Scholar]

- Birt, E. ‘I have never seen such devotion to duty. They are all angels.’—Newport woman on coronavirus treatment and how she needs your help to repay NHS staff. South Wales Argus, 10 May 2020; 6. [Google Scholar]

- McInne, K. ‘A lot of people have stepped up and are working long hours’; Adult social care director hails city’s ‘fantastic’ response. Stoke The Sentinel, 15 April 2020; 7. [Google Scholar]

- McInnes, K. Meet and greet service when leaving hospital; Door-to-door taxis for vulnerable patients. Stoke The Sentinel, 9 May 2020; 4. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, A. Pulling together to help frontline. South Wales Echo, 20 April 2020; 3. [Google Scholar]

- Mullin, C. These elderly people are so vulnerable—It’s our job to look after them; With the Grand National cancelled, the ECHO has launched You Bet We Care, to encourage readers to donate their stake to Liverpool City Region Metro Mayor Steve Rotheram’s £1m fundraising campaign—LCR Cares. Here’s an example of how the cash could be used. Liverpool Echo, 2 April 2020; 12. [Google Scholar]

- Waters, H. Picture of Selflessness. Daily Mail, 4 April 2020; 14. [Google Scholar]

- Brawn, S. Medicine and food parcels are on the way. Paisley Daily Express, 4 April 2020; 3. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, G. Team effort gets tablet computers to most vulnerable. Wirral Globe, 2020; 12. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, A. 350 iPads to be delivered to care homes and hospitals across North Wales to help people stay in touch with family. Denbighshire Free Press, 23 April 2020; 7. [Google Scholar]

- Anon. We are working really hard as a care community. Carmarthen Journal, 22 April 2020; 5. [Google Scholar]

- Barron, D. How are our pharmacists coping with Covid crisis? The coronavirus has transformed the way chemists are working. Here they speak about how they, their staff and their customers are dealing with the new situation. The Irish Times, 21 April 2020; 16. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, L. Heroes of home front. The Sun, 4 April 2020; 4. [Google Scholar]

- Fegan, C. ‘The panic was huge, but we had to work as a team to give best care’; How Covid-19 ravaged the country’s biggest home for the elderly. Irish Independent, 29 April 2020; 12. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, K. Front line lives: Care home staff on working through Covid-19. The National (Scotland), 10 May 2020; 6. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, B. ‘It’s an honour to be the one holding their hand.’ Inside a Welsh care home dealing with the enormity of coronavirus; during their worst week the care home had nine residents who were on end of life support. WalesOnline, 11 May 2020; 8. [Google Scholar]

- Anon. Heroes of the Corona Crisis; We’re all trying to do our bit to help the NHS, but as these truly inspiring; stories show, there’s an unsung army of selfless people. Scottish Daily Mail, 14 April 2020; 6. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, S. ‘On the first day I was really worried I wouldn’t make it’—Man, 64, reveals coronavirus. The Argus, 8 May 2020; 8. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, R. MP praise for coronavirus lifeline. Ayr Advertiser, 9 April 2020; 9. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, R. “We haven’t had time to grieve” Care homes struggle as Covid-19 deaths rise. UK’s largest provider says 10% of all staff are self-isolating as lack of PPE testing takes toll across the sector. The Guardian, 9 April 2020; 11. [Google Scholar]

- Gillies, K. Bucks-based home care go ‘above and beyond’ for clients and employees. Bucks Free Press, 11 May 2020; 8. [Google Scholar]

- Anon. So how has primary care cover in the bay region been reorganised to meet the challenges which lay ahead? South Wales Echo, 17 April 2020; 4. [Google Scholar]

- Meddings, S. We’re all in this together; Links between private and public healthcare forged in the pandemic will live on, says Spire chief Justin Ash. The Sunday Times, 10 May 2020; 15. [Google Scholar]

- Heinen, N. “Plan the exit now? I wouldn’t have time for that”; Emergency clinics are being set up in several large cities and the retirement homes are being converted, including Cologne. The head of the health department there is concerned about the rising number of corona deaths. Johannes Niessen makes serious accusations against politicians. Die Welt, 6 April 2020; 3. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, M. New Covid-19 rehabilitation hospital to open in former TB wards. Sunday Independent, 3 May 2020; 8. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, M. Inside the Mater’s war on Covid-19; if the beds run out, we’ll drop special medical pods in the car park, hospital chief executive Alan Sharp tells Maeve Sheehan. Sunday Independent, 22 March 2020; 12. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, R. Health and social care coronavirus pledge given by NHS and North Lanarkshire Council; Working whenever possible as a single organisation, the approach will be to deliver and manage many health and social care services across Lanarkshire. Daily Record, 18 March 2020; 12. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, K. Heroic staff go into 24/7 quarantine for a MONTH with OAPs. Scottish Mail on Sunday, 12 April 2020; 3. [Google Scholar]

- Anon. Elderly in Transfer to Udston Hospital. Wishaw Press, 8 April 2020; 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anon. ‘Step up to the mark’: Council transforms social care services to look after the elderly. Craven Herald and Pioneer, 10 April 2020; 4. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, C.; Eysenbach, G. Pandemics in the Age of Twitter: Content Analysis of Tweets during the 2009 H1N1 Outbreak. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e14118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sy, M.; O’Leary, N.; Nagraj, S.; El-Awaisi, A.; O’Carroll, V.; Xyrichis, A. doing Interprofessional Research in the COVID-19 Era: A Discussion Paper. J. Interprof. 2020, 27, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragazzi, N.L.; Mansour, M.; Bonsignore, A.; Ciliberti, R. The Role of Hospital and Community Pharmacists in the Management of COVID-19: Towards an Expanded Definition of the Roles, Responsibilities, and Duties of the Pharmacist. Pharmacy 2020, 8, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyashanu, M.; Pfende, F.; Ekpenyong, M. Exploring the Challenges Faced by Frontline Workers in Health and Social Care amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: Experiences of Frontline Workers in the English Midlands Region, UK. J. Interprof. 2020, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Natale, J.; Boehmer, J.; Blumberg, D.A.; Dimitriades, C.; Hirose, S.; Kair, L.R.; Kirk, J.D.; Mateev, S.N.; McKnight, H.; Plant, J.; et al. Interprofessional/Interdisciplinary Teamwork during the Early COVID-19 Pandemic: Experience from a Children’s Hospital within an Academic Health Center. J. Interprof. 2020, 16, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesco, M.; Perazzo, P.; Bottinelli, E.; Possenti, F.; Banfi, G. Managing a Tertiary Orthopedic Hospital during the COVID-19 Epidemic, Main Challenges and Solutions Adopted. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molloy, D.W.; O’Sullivan, C.; O’Caoimh, R.; Duggan, E.; McGrath, K.; Nolan, M.; Hennessy, J.; O’Keeffe, G.; O’Connor, K. The Experience of Managing Covid-19 in Irish Nursing Homes in 2020: Cork–Kerry Community Healthcare, Cork Ireland. J. Nurs. Home Res. 2020, 6, 47–49. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, E.; Tierney, E.; Shé, Éidín N, N.; Killilea, M.; Donaghey, C.; Daly, A.; Roche, M.; Mac Loughlin, D.; Dinneen, S.F.; Panel, P.I. COVID-19: Public and patient involvement, now more than ever. HRB Open Res. 2020, 3, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Geriatrics Society. COVID-19: BGS Statement on Research for Older People during the COVID-19 Pandemic. 1 April 2020. Available online: https://www.bgs.org.uk/resources/covid-19-bgs-statement-on-research-for-older-people-during-the-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 20 June 2020).

| All of these Words | New Ways of Working |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Any of these Words | Health and Social Care OR Health or Social OR Care |

| Dates | 1 March 2020 and the 11 May 2020 |

| Theme | Tweets | Tweets Supporting the Theme |

|---|---|---|

| Using telehealth and/or phone consultations to provide ongoing care to patients | 71 | We will definitely keep this moving forward and continue to embrace the new ways of working. Primary care is now a blend of face to face and digital medicine. Safety first as always. Many of my patients happy to share video consultations but important to remember not everyone has tech still. 9 May 2020 |

| The Nurse Service is here to support any families caring for someone with dementia during this difficult and worrying time (new ways of working- telephone clinics, consultations, practical help, advice and support) supporting our community. 21 April 2020 | ||

| First #telehealth call with my youngest child today. In 20 mins he went from hiding and running from camera to smiling and waving. So grateful to parents for their flexibility and patience as we find new ways of working. #mySLTday. 20 March 2020 | ||

| Learning new ways of working during #COVID-19. Did ward round in psychiatry with registrar, nurse and OT in room with patient and consultant on Webex due to having to isolate. Patients coped quite well. 19 March 2020 | ||

| Interprofessional Work | 79 | “It’s changed beyond recognition”—Many of our staff have had to find new ways of working, or take on new roles entirely, and the response has been brilliant. 1 April 2020 |

| I’m so impressed with the speed that our staff have implemented and adapted to new ways of working to provide therapeutic interventions during the barriers that face us in this challenging time. #Covid_19 #NHSheroes 20 March 2020 | ||

| Community spirit, Covid-19 shows the true strength of interdisciplinary cooperation and cross boundary working, no time for “me” or professional boundaries that are barriers to common good. New ways of working and long may they last! 14 March 2020 | ||

| Doctors and HCW are working together at all levels to prepare for an outbreak of #COVID-19 in the coming weeks. Whatever is required we will be there, delivering care. This may require redeployment and new ways of working, and we will do our best and our duty. 10 March 2020 | ||

| Team meetings using online platforms | 22 | Working in new ways in our perinatal mental health team: Teams enables us to huddle with a virtual huddle board, & team drop-in at end of day: chance to think, connect and be ready for next day. + less emails and more conversations mean faster progress. Adapting positively. 6 April 2020 |

| It’s a strange time but look we did a virtual handover yesterday. Community nurses are used to mobile working and problem solving. 22 March 2020 | ||

| Teams testing out #Webex today. Checking in with our staff across primary care team, keeping ourselves up to date with new norms and new ways of working. 21 March 2020 | ||

| ED ACPs ENPs and Team SDEC evening get together in this new world, comes new ways of working, connecting and learning. 19 March 2020 | ||

| Trust and collaboration within teams | 18 | Local relationships, trust & new ways of working at the heart of health & social care integration/wider service reform have been the bedrock of our ability to respond to C-19. They have to continue be the foundation of what we do next. 10 May 2020 |

| The last few weeks have brought challenges, gripes and niggles to say the least. However, they have also brought new and innovative ways of working with all different staff groups! Diversity and Inclusion have produced teamwork for a shared goal #CriticalCare 29 April 2020 | ||

| My colleagues (SHOs, SpRs, consultants) have all been amazing. We have changed to completely different ways of working - more weekends, nightshifts, new clinical challenges. Everyone has come on board and we’ve retained a really high morale despite the stress everyone is under. 18 April 2020 | ||

| We look for the positives at work. Things we have noticed are how quickly we can adapt to new ways of working. Clear channels for communication Even more #kindness from local community and between colleagues. 3 April 2020 | ||

| Sharing information and a clear feedback loop between teams | 16 | Thank you from the leadership team to all our Older Adult Services teams in #Location- you’ve continued to work tirelessly to provide the best care possible & embrace new ways of working. Feedback has been really positive. Well done! #OurNHSPeople 29 April 2020 |

| We know that a lot of our teams are adjusting to new ways of working, so we’ve set up a Clinical Support line to provide mentoring and reassurance. 21 April 2020 | ||

| Due to #COVID-19 you may find yourself working in different ways, different settings or with new teams. Our guidance for support workers in health & social care include team working in rapidly changing environments, keeping a record of care & communication. 17 April 2020 | ||

| Social distancing means people are getting used to new ways of working. Today colleagues joined us to learn how they can work together & collaborate virtually: we look forward to seeing how you put your learning into action. 19 March 2020 | ||

| Team felt empowered to change at a local level | 111 | We now have to look through a new lens as to how we deliver health services in Ireland. We need to retain some of our responses for #Covid-19 as they have proven good for the public. Working closer with GPs and unlocking the huge passion of staff are just two. 26 April 2020 |

| There have been countless innovations & new ways of working. Changes that might have taken years have been achieved in days in hospitals, mental health, GP & community services. As one leader said, we’re not going back to normal, we must embrace a new & very different future. 18 April 2020 | ||

| So many examples of great teamwork and leadership. Over the past few weeks - discharge pathways completely rewritten, different ways of working implemented and new teams formed. Very proud of everyone’s effort and resolve. 7 April 2020 | ||

| I have never known so much change happen so quickly. Honestly the NHS in a crisis is amazing, people working together all over the place and achieving so much and developing new ways of working. All with care and compassion for each other and the patients. 26 March 2020 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ní Shé, É.; O’Donnell, D.; O’Shea, M.; Stokes, D. New Ways of Working? A Rapid Exploration of Emerging Evidence Regarding the Care of Older People during COVID19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6442. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17186442

Ní Shé É, O’Donnell D, O’Shea M, Stokes D. New Ways of Working? A Rapid Exploration of Emerging Evidence Regarding the Care of Older People during COVID19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(18):6442. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17186442

Chicago/Turabian StyleNí Shé, Éidín, Deirdre O’Donnell, Marie O’Shea, and Diarmuid Stokes. 2020. "New Ways of Working? A Rapid Exploration of Emerging Evidence Regarding the Care of Older People during COVID19" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 18: 6442. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17186442