Multi-Functionalized Nanomaterials and Nanoparticles for Diagnosis and Treatment of Retinoblastoma

Abstract

:1. Introduction

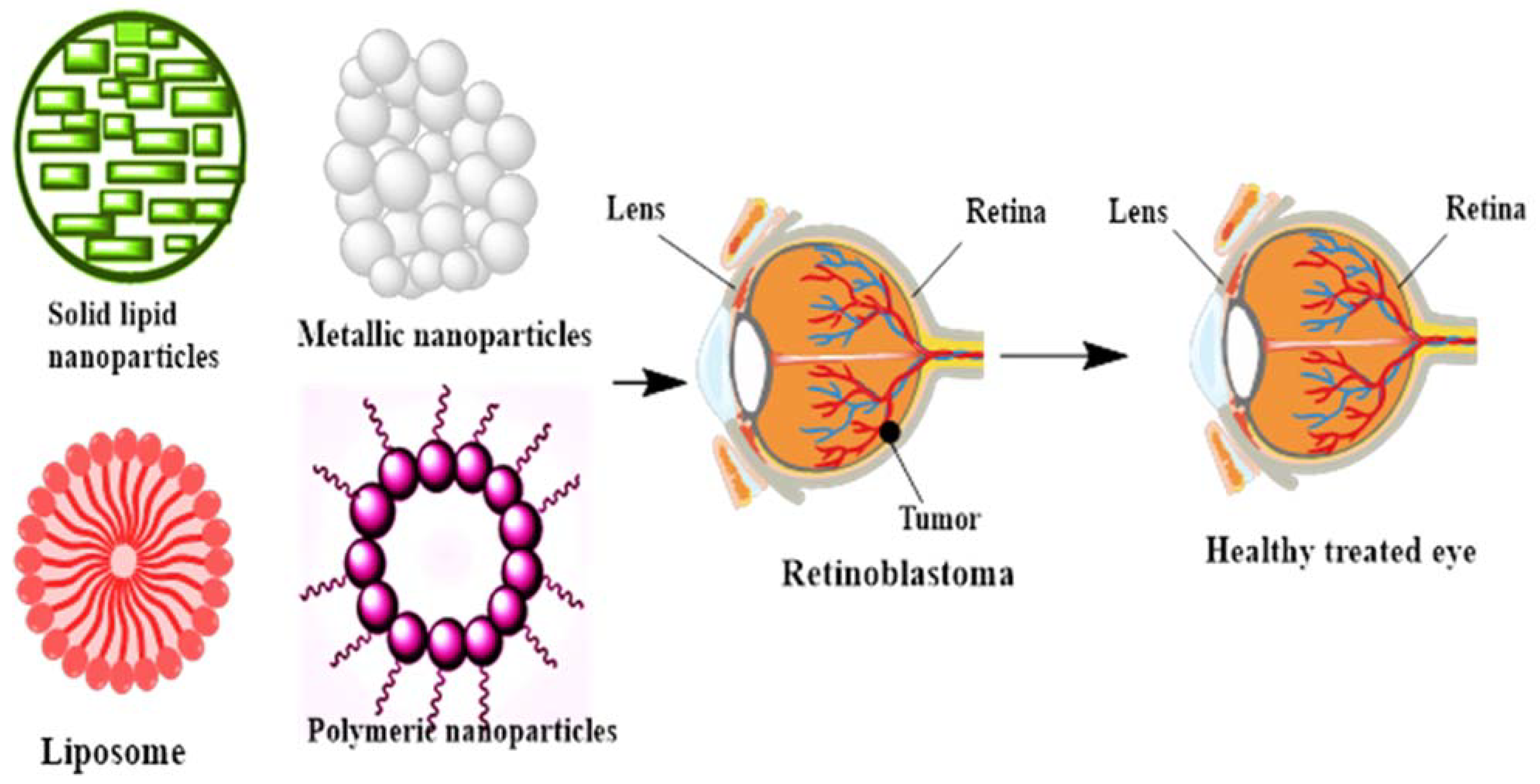

2. The Role of Nanotechnology in the Diagnosis of Retinoblastoma

3. Nanoparticles in Treatment of RB

4. Multi-Functionalized Nanocarrier Therapies for Targeting RB

4.1. Surface-Modified Melphalan Nanoparticles for the Intravitreal Chemotherapy of RB

4.2. Galactose Functionalized Nanocarriers

4.3. Hyaluronic Acid (HA) Functionalized Nanocarriers

4.4. Folic Acid (FA) Functionalized Nanocarriers

5. Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs)

5.1. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs)

5.2. Nanoliposomes

6. Metallic Nanoparticles

6.1. Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs)

6.2. Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs)

7. Conclusions, Challenges and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| AgNPs | Silver nanoparticles |

| CD44 | Cluster of differentiation 44 |

| CNPs | Chitosan NPs |

| DCM | Dichloromethane |

| DOX | Doxorubicin |

| EDTA | Ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid |

| FA | Folic acid |

| Fe3O4 | Iron oxide |

| GNPs | Gold nanoparticles |

| LNPs | lipid nanoparticles |

| MDP | Muramyl dipeptide |

| PFP | Per fluoro pentane |

| PLGA | Poly-d,l-lactic-co-glycolic acid |

| RB | Retinoblastoma |

References

- Fabian, I.D.; Onadim, Z.; Karaa, E.; Duncan, C.; Chowdhury, T.; Scheimberg, I.; Ohnuma, S.-I.; Reddy, M.A.; Sagoo, M.S. The management of retinoblastoma. Oncogene 2018, 37, 1551–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balmer, A.; Munier, F. Differential diagnosis of leukocoria and strabismus, first presenting signs of retinoblastoma. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2007, 1, 431. [Google Scholar]

- Parveen, S.; Sahoo, S.K. Evaluation of cytotoxicity and mechanism of apoptosis of doxorubicin using folate-decorated chitosan nanoparticles for targeted delivery to retinoblastoma. Cancer Nanotechnol. 2010, 1, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Balmer, A.; Zografos, L.; Munier, F. Diagnosis and current management of retinoblastoma. Oncogene 2006, 25, 5341–5349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lohmann, D.R.; Gerick, M.; Brandt, B.; Oelschläger, U.; Lorenz, B.; Passarge, E.; Horsthemke, B. Constitutional RB1-gene mutations in patients with isolated unilateral retinoblastoma. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997, 61, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shields, C.L.; Shields, J.A. Diagnosis and management of retinoblastoma. Cancer Control 2004, 11, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jockovich, M.-E.; Bajenaru, M.L.; Pina, Y.; Suarez, F.; Feuer, W.; Fini, M.E.; Murray, T.G. Retinoblastoma tumor vessel maturation impacts efficacy of vessel targeting in the LHBETATAG mouse model. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007, 48, 2476–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shields, C.L.; Shields, J.A.; De Potter, P.; Minelli, S.; Hernandez, C.; Brady, L.W.; Cater, J.R. Plaque radiotherapy in the management of retinoblastoma: Use as a primary and secondary treatment. Ophthalmology 1993, 100, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphree, A.L.; Villablanca, J.G.; Deegan, W.F.; Sato, J.K.; Malogolowkin, M.; Fisher, A.; Parker, R.; Reed, E.; Gomer, C.J. Chemotherapy plus local treatment in the management of intraocular retinoblastoma. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1996, 114, 1348–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.; Gallie, B.L.; Munier, F.L.; Beck, M.P. Chemotherapy for retinoblastoma. Ophthalmol. Clin. North Am. 2005, 18, 55–63, viii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, W.F. Emerging strategies for the treatment of retinoblastoma. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2003, 14, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.-Y.; Hao, J.-L.; Wang, S.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, W.-S. Nanoparticles in the ocular drug delivery. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2013, 6, 390. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thrimawithana, T.R.; Young, S.; Bunt, C.R.; Green, C.; Alany, R.G. Drug delivery to the posterior segment of the eye. Drug Discov. Today 2011, 16, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranei, M.; Taheri, R.A.; Tirgar, M.; Saeidi, A.; Oroojalian, F.; Uzun, L.; Asefnejad, A.; Wurm, F.R.; Goodarzi, V. Anticancer effect of green tea extract (GTE)-Loaded pH-responsive niosome Coated with PEG against different cell lines. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 26, 101751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barani, M.; Bilal, M.; Rahdar, A.; Arshad, R.; Kumar, A.; Hamishekar, H.; Kyzas, G.Z. Nanodiagnosis and nanotreatment of colorectal cancer: An overview. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2021, 23, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barani, M.; Bilal, M.; Sabir, F.; Rahdar, A.; Kyzas, G.Z. Nanotechnology in ovarian cancer: Diagnosis and treatment. Life Sci. 2020, 266, 118914. [Google Scholar]

- Barani, M.; Mirzaei, M.; Mahani, M.T.; Nematollahi, M.H. Lawsone-loaded Niosome and its Antitumor Activity in MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cell Line: A Nano-herbal Treatment for Cancer. DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barani, M.; Mirzaei, M.; Torkzadeh-Mahani, M.; Adeli-Sardou, M. Evaluation of carum-loaded niosomes on breast cancer cells: Physicochemical properties, in vitro cytotoxicity, flow cytometric, DNA fragmentation and cell migration assay. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murray, T.G.; Cicciarelli, N.; O’Brien, J.M.; Hernandez, E.; Mueller, R.L.; Smith, B.J.; Feuer, W. Subconjunctival carboplatin therapy and cryotherapy in the treatment of transgenic murine retinoblastoma. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1997, 115, 1286–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.J.; Durairaj, C.; Kompella, U.B.; O’Brien, J.M.; Grossniklaus, H.E. Subconjunctival nanoparticle carboplatin in the treatment of murine retinoblastoma. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2009, 127, 1043–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Quill, K.R.; Dioguardi, P.K.; Tong, C.T.; Gilbert, J.A.; Aaberg, T.M., Jr.; Grossniklaus, H.E.; Edelhauser, H.F.; O’Brien, J.M. Subconjunctival carboplatin in fibrin sealant in the treatment of transgenic murine retinoblastoma. Ophthalmology 2005, 112, 1151–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Si, P.; de la Zerda, A.; Jokerst, J.V.; Myung, D. Gold nanoparticles to enhance ophthalmic imaging. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 367–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eide, N.; Walaas, L. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy and other biopsies in suspected intraocular malignant disease: A review. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009, 87, 588–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barani, M.; Mirzaei, M.; Torkzadeh-Mahani, M.; Lohrasbi-Nejad, A.; Nematollahi, M.H. A new formulation of hydrophobin-coated niosome as a drug carrier to cancer cells. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 113, 110975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barani, M.; Mukhtar, M.; Rahdar, A.; Sargazi, G.; Thysiadou, A.; Kyzas, G.Z. Progress in the Application of Nanoparticles and Graphene as Drug Carriers and on the Diagnosis of Brain Infections. Molecules 2021, 26, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barani, M.; Nematollahi, M.H.; Zaboli, M.; Mirzaei, M.; Torkzadeh-Mahani, M.; Pardakhty, A.; Karam, G.A. In silico and in vitro study of magnetic niosomes for gene delivery: The effect of ergosterol and cholesterol. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 94, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barani, M.; Sabir, F.; Rahdar, A.; Arshad, R.; Kyzas, G.Z. Nanotreatment and Nanodiagnosis of Prostate Cancer: Recent Updates. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barani, M.; Torkzadeh-Mahani, M.; Mirzaei, M.; Nematollahi, M.H. Comprehensive evaluation of gene expression in negative and positive trigger-based targeting niosomes in HEK-293 cell line. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. IJPR 2020, 19, 166. [Google Scholar]

- Bilal, M.; Barani, M.; Sabir, F.; Rahdar, A.; Kyzas, G.Z. Nanomaterials for the treatment and diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: An overview. NanoImpact 2020, 100251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.S.; Bharadwaj, P.; Bilal, M.; Barani, M.; Rahdar, A.; Taboada, P.; Bungau, S.; Kyzas, G.Z. Stimuli-responsive polymeric nanocarriers for drug delivery, imaging, and theragnosis. Polymers 2020, 12, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davarpanah, F.; Yazdi, A.K.; Barani, M.; Mirzaei, M.; Torkzadeh-Mahani, M. Magnetic delivery of antitumor carboplatin by using PEGylated-Niosomes. DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 26, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, A.K.; Barani, M.; Sheikhshoaie, I. Fabrication of a new superparamagnetic metal-organic framework with core-shell nanocomposite structures: Characterization, biocompatibility, and drug release study. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 92, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghazy, E.; Kumar, A.; Barani, M.; Kaur, I.; Rahdar, A.; Behl, T. Scrutinizing the Therapeutic and Diagnostic Potential of Nanotechnology in Thyroid Cancer: Edifying drug targeting by nano-oncotherapeutics. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 102221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazy, E.; Rahdar, A.; Barani, M.; Kyzas, G.Z. Nanomaterials for Parkinson disease: Recent progress. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 129698. [Google Scholar]

- Hajizadeh, M.R.; Maleki, H.; Barani, M.; Fahmidehkar, M.A.; Mahmoodi, M.; Torkzadeh-Mahani, M. In vitro cytotoxicity assay of D-limonene niosomes: An efficient nano-carrier for enhancing solubility of plant-extracted agents. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 14, 448. [Google Scholar]

- Hajizadeh, M.R.; Parvaz, N.; Barani, M.; Khoshdel, A.; Fahmidehkar, M.A.; Mahmoodi, M.; Torkzadeh-Mahani, M. Diosgenin-loaded niosome as an effective phytochemical nanocarrier: Physicochemical characterization, loading efficiency, and cytotoxicity assay. DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 27, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahin, N.; Anwar, R.; Tewari, D.; Kabir, M.T.; Sajid, A.; Mathew, B.; Uddin, M.S.; Aleya, L.; Abdel-Daim, M.M. Nanoparticles and its biomedical applications in health and diseases: Special focus on drug delivery. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, X.-Y.; Merlin, D.; Xiao, B. Recent advances in orally administered cell-specific nanotherapeutics for inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 7718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Liu, J.; Jin, S.; Guo, W.; Liang, X.; Hu, Z. Nanotechnology-based strategies for treatment of ocular disease. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2017, 7, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kompella, U.B.; Amrite, A.C.; Ravi, R.P.; Durazo, S.A. Nanomedicines for back of the eye drug delivery, gene delivery, and imaging. Prog. Retinal Eye Res. 2013, 36, 172–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruchit, T.; Tyagi, P.; Vooturi, S.; Kompella, U. Deslorelin and transferrin mono-and dual-functionalized nanomicelles for drug delivery to the anterior segment of the eye. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, 3203. [Google Scholar]

- Sahay, G.; Alakhova, D.Y.; Kabanov, A.V. Endocytosis of nanomedicines. J. Control. Release 2010, 145, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scheinman, R.I.; Trivedi, R.; Vermillion, S.; Kompella, U.B. Functionalized STAT1 siRNA nanoparticles regress rheumatoid arthritis in a mouse model. Nanomedicine 2011, 6, 1669–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinman, M.E.; Yamada, K.; Takeda, A.; Chandrasekaran, V.; Nozaki, M.; Baffi, J.Z.; Albuquerque, R.J.; Yamasaki, S.; Itaya, M.; Pan, Y. Sequence-and target-independent angiogenesis suppression by siRNA via TLR3. Nature 2008, 452, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sundaram, S.; Roy, S.K.; Ambati, B.K.; Kompella, U.B. Surface-functionalized nanoparticles for targeted gene delivery across nasal respiratory epithelium. FASEB J. 2009, 23, 3752–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Conley, S.M.; Naash, M.I. Nanoparticles for retinal gene therapy. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2010, 29, 376–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mitra, M.; Misra, R.; Harilal, A.; Sahoo, S.K.; Krishnakumar, S. Enhanced in vitro antiproliferative effects of EpCAM antibody-functionalized paclitaxel-loaded PLGA nanoparticles in retinoblastoma cells. Mol. Vis. 2011, 17, 2724. [Google Scholar]

- Hasanein, P.; Rahdar, A.; Barani, M.; Baino, F.; Yari, S. Oil-In-Water Microemulsion Encapsulation of Antagonist Drugs Prevents Renal Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Rats. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, M.; Bilal, M.; Rahdar, A.; Barani, M.; Arshad, R.; Behl, T.; Brisc, C.; Banica, F.; Bungau, S. Nanomaterials for Diagnosis and Treatment of Brain Cancer: Recent Updates. Chemosensors 2020, 8, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikazar, S.; Barani, M.; Rahdar, A.; Zoghi, M.; Kyzas, G.Z. Photo-and Magnetothermally Responsive Nanomaterials for Therapy, Controlled Drug Delivery and Imaging Applications. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 12590–12609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahdar, A.; Hajinezhad, M.R.; Nasri, S.; Beyzaei, H.; Barani, M.; Trant, J.F. The synthesis of methotrexate-loaded F127 microemulsions and their in vivo toxicity in a rat model. J. Mol. Liquids 2020, 313, 113449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahdar, A.; Hajinezhad, M.R.; Sargazi, S.; Barani, M.; Bilal, M.; Kyzas, G.Z. Deferasirox-loaded pluronic nanomicelles: Synthesis, characterization, in vitro and in vivo studies. J. Mol. Liquids 2021, 323, 114605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahdar, A.; Hajinezhad, M.R.; Sargazi, S.; Bilal, M.; Barani, M.; Karimi, P.; Kyzas, G.Z. Biochemical effects of deferasirox and deferasirox-loaded nanomicellesin iron-intoxicated rats. Life Sci. 2021, 119146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahdar, A.; Taboada, P.; Hajinezhad, M.R.; Barani, M.; Beyzaei, H. Effect of tocopherol on the properties of Pluronic F127 microemulsions: Physico-chemical characterization and in vivo toxicity. J. Mol. Liquids 2019, 277, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barani, M.; Mukhtar, M.; Rahdar, A.; Sargazi, S.; Pandey, S.; Kang, M. Recent Advances in Nanotechnology-Based Diagnosis and Treatments of Human Osteosarcoma. Biosensors 2021, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkzadeh-Mahani, M.; Zaboli, M.; Barani, M.; Torkzadeh-Mahani, M. A combined theoretical and experimental study to improve the thermal stability of recombinant D-lactate dehydrogenase immobilized on a novel superparamagnetic Fe3O4NPs@ metal–organic framework. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2020, 34, e5581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordray, M.S.; Amdahl, M.; Richards-Kortum, R.R. Gold nanoparticle aggregation for quantification of oligonucleotides: Optimization and increased dynamic range. Anal. Biochem. 2012, 431, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Donaldson, K.; Schinwald, A.; Murphy, F.; Cho, W.-S.; Duffin, R.; Tran, L.; Poland, C. The biologically effective dose in inhalation nanotoxicology. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, K.; Usui, Y.; Goto, H. Clinical features and diagnostic significance of the intraocular fluid of 217 patients with intraocular lymphoma. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2012, 56, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, L. Analysis of the incidence of intraocular metastasis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1993, 77, 149–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dimaras, H.; Kimani, K.; Dimba, E.A.; Gronsdahl, P.; White, A.; Chan, H.S.; Gallie, B.L. Retinoblastoma. Lancet 2012, 379, 1436–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rao, R.; Honavar, S.G. Retinoblastoma. Indian J. Pediatrics 2017, 84, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattosinho, C.C.D.S.; Moura, A.T.M.; Oigman, G.; Ferman, S.E.; Grigorovski, N. Time to diagnosis of retinoblastoma in Latin America: A systematic review. Pediatric Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 36, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacalone, M.; Mastrangelo, G.; Parri, N. Point-of-care ultrasound diagnosis of retinoblastoma in the emergency department. Pediatric Emerg. Care 2018, 34, 599–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, S.A.; Ong, G.Y.-K. Use of Ocular Point-of-Care Ultrasound in a Difficult Pediatric Examination: A Case Report of an Emergency Department Diagnosis of Retinoblastoma. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 58, 632–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Guo, J.; Xu, X.; Wang, Y.; Mukherji, S.K.; Xian, J. Diagnosis of Postlaminar optic nerve invasion in retinoblastoma with MRI features. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2020, 51, 1045–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, R.; Gaudana, R.; Boddu, S.H. Imaging techniques in the diagnosis and management of ocular tumors: Prospects and challenges. AAPS J. 2018, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Xi, H.-Y.; Shao, Q.; Liu, Q.-H. Biomarkers in retinoblastoma. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 13, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golabchi, K.; Soleimani-Jelodar, R.; Aghadoost, N.; Momeni, F.; Moridikia, A.; Nahand, J.S.; Masoudifar, A.; Razmjoo, H.; Mirzaei, H. MicroRNAs in retinoblastoma: Potential diagnostic and therapeutic biomarkers. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 3016–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.-J.; Zhang, X.-Q.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, G. Nanotechnology: A promising method for oral cancer detection and diagnosis. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2018, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabir, F.; Barani, M.; Rahdar, A.; Bilal, M.; Zafar, N.M.; Bungau, S.; Kyzas, G.Z. How to Face Skin Cancer with Nanomaterials: A Review. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2021, 11, 11931–11955. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Gao, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, T. Nanotechnology in cancer diagnosis: Progress, challenges and opportunities. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, H.; Van Phuc Nguyen, P.M.; Jung, M.J.; Kim, S.W.; Oh, J.; Kang, H.W. Doxorubicin-fucoidan-gold nanoparticles composite for dual-chemo-photothermal treatment on eye tumors. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 113719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cruz-Alonso, M.; Fernandez, B.; Álvarez, L.; González-Iglesias, H.; Traub, H.; Jakubowski, N.; Pereiro, R. Bioimaging of metallothioneins in ocular tissue sections by laser ablation-ICP-MS using bioconjugated gold nanoclusters as specific tags. Microchim. Acta 2018, 185, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lapierre-Landry, M.; Gordon, A.Y.; Penn, J.S.; Skala, M.C. In vivo photothermal optical coherence tomography of endogenous and exogenous contrast agents in the eye. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaidev, L.; Chellappan, D.R.; Bhavsar, D.V.; Ranganathan, R.; Sivanantham, B.; Subramanian, A.; Sharma, U.; Jagannathan, N.R.; Krishnan, U.M.; Sethuraman, S. Multi-functional nanoparticles as theranostic agents for the treatment & imaging of pancreatic cancer. Acta Biomater. 2017, 49, 422–433. [Google Scholar]

- Toda, M.; Yukawa, H.; Yamada, J.; Ueno, M.; Kinoshita, S.; Baba, Y.; Hamuro, J. In vivo fluorescence visualization of anterior chamber injected human corneal endothelial cells labeled with quantum dots. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2019, 60, 4008–4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goto, K.; Kato, D.; Sekioka, N.; Ueda, A.; Hirono, S.; Niwa, O. Direct electrochemical detection of DNA methylation for retinoblastoma and CpG fragments using a nanocarbon film. Anal. Biochem. 2010, 405, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yang, Q.; Li, M.; Zou, H.; Wang, Z.; Ran, H.; Zheng, Y.; Jian, J.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, Y.; et al. Multifunctional Nanoparticles for Multimodal Imaging-Guided Low-Intensity Focused Ultrasound/Immunosynergistic Retinoblastoma Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 5642–5657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, I.; Vichare, R.; Paulson, R.; Appavu, R.; Panguluri, S.K.; Tzekov, R.; Sahiner, N.; Ayyala, R.; Biswal, M.R. Carbon dots fabrication: Ocular imaging and therapeutic potential. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwat, S.; Stapleton, F.; Willcox, M.; Roy, M. Quantum Dots in Ophthalmology: A Literature Review. Curr. Eye Res. 2019, 44, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahan, M.M.; Doiron, A.L. Gold nanoparticles as X-ray, CT, and multimodal imaging contrast agents: Formulation, targeting, and methodology. J. Nanomater. 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altundal, Y.; Sajo, E.; Makrigiorgos, G.M.; Berbeco, R.I.; Ngwa, W. Nanoparticle-aided radiotherapy for retinoblastoma and choroidal melanoma. In Proceedings of the World Congress on Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering, Toronto, ON, Canada, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 907–910. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi, S.; Mokhtari-Dizaji, M.; Ghassemi, F.; Sheibani, S.; Asadi Amoli, F. Increasing the efficiency of the retinoblastoma brachytherapy protocol with ultrasonic hyperthermia and gold nanoparticles: A rabbit model. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2020, 96, 1614–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohajeri, M.; Behnam, B.; Sahebkar, A. Biomedical applications of carbon nanomaterials: Drug and gene delivery potentials. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 298–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Power, A.C.; Gorey, B.; Chandra, S.; Chapman, J. Carbon nanomaterials and their application to electrochemical sensors: A review. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2018, 7, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzin, A.; Etesami, S.A.; Quint, J.; Memic, A.; Tamayol, A. Magnetic nanoparticles in cancer therapy and diagnosis. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2020, 9, 1901058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzameret, A.; Ketter-Katz, H.; Edelshtain, V.; Sher, I.; Corem-Salkmon, E.; Levy, I.; Last, D.; Guez, D.; Mardor, Y.; Margel, S. In vivo MRI assessment of bioactive magnetic iron oxide/human serum albumin nanoparticle delivery into the posterior segment of the eye in a rat model of retinal degeneration. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2019, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimaras, H.; Corson, T.W.; Cobrinik, D.; White, A.; Zhao, J.; Munier, F.L.; Abramson, D.H.; Shields, C.L.; Chantada, G.L.; Njuguna, F. Retinoblastoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2015, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jain, M.; Rojanaporn, D.; Chawla, B.; Sundar, G.; Gopal, L.; Khetan, V. Retinoblastoma in Asia. Eye 2019, 33, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mehyar, M.; Mosallam, M.; Tbakhi, A.; Saab, A.; Sultan, I.; Deebajah, R.; Jaradat, I.; AlJabari, R.; Mohammad, M.; AlNawaiseh, I. Impact of RB1 gene mutation type in retinoblastoma patients on clinical presentation and management outcome. Hematol. Oncol. Stem Cell Ther. 2020, 13, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocarta, A.-I.; Hobzova, R.; Sirc, J.; Cerna, T.; Hrabeta, J.; Svojgr, K.; Pochop, P.; Kodetova, M.; Jedelska, J.; Bakowsky, U. Hydrogel implants for transscleral drug delivery for retinoblastoma treatment. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 103, 109799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, K.; Ren, H.; Meng, F.; Zhang, R.; Qian, J. Ocular toxicity of intravitreal melphalan for retinoblastoma in Chinese patients. BMC Ophthalmol. 2019, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kleinerman, R.A.; Tucker, M.A.; Sigel, B.S.; Abramson, D.H.; Seddon, J.M.; Morton, L.M. Patterns of cause-specific mortality among 2053 survivors of retinoblastoma, 1914–2016. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019, 111, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimaras, H.; Corson, T.W. Retinoblastoma, the visible CNS tumor: A review. J. Neurosci. Res. 2019, 97, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Raguraman, R.; Parameswaran, S.; Kanwar, J.R.; Khetan, V.; Rishi, P.; Kanwar, R.K.; Krishnakumar, S. Evidence of tumour microenvironment and stromal cellular components in retinoblastoma. Ocular Oncol. Pathol. 2019, 5, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Herrero, E.; Fernández-Medarde, A. Advanced targeted therapies in cancer: Drug nanocarriers, the future of chemotherapy. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2015, 93, 52–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jabr-Milane, L.S.; van Vlerken, L.E.; Yadav, S.; Amiji, M.M. Multi-functional nanocarriers to overcome tumor drug resistance. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2008, 34, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mendoza, P.R.; Grossniklaus, H.E. Therapeutic options for retinoblastoma. Cancer Control 2016, 23, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhavsar, D.; Subramanian, K.; Sethuraman, S.; Krishnan, U.M. Management of retinoblastoma: Opportunities and challenges. Drug Deliv. 2016, 23, 2488–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, R.; Mitra, R.N.; Zheng, M.; Wang, K.; Dahringer, J.C.; Han, Z. Developing Nanoceria-Based pH-Dependent Cancer-Directed Drug Delivery System for Retinoblastoma. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1806248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, L.B.; Tyo, K.M.; Stocke, S.; Mahmoud, M.Y.; Ramasubramanian, A.; Steinbach-Rankins, J.M. Surface-Modified Melphalan Nanoparticles for Intravitreal Chemotherapy of Retinoblastoma. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2019, 60, 1696–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godse, R.; Rathod, M.; De, A.; Shinde, U. Intravitreal galactose conjugated polymeric nanoparticles of etoposide for retinoblastoma. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 61, 102259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, T.F.; Peynshaert, K.; Nascimento, T.L.; Fattal, E.; Karlstetter, M.; Langmann, T.; Picaud, S.; Demeester, J.; De Smedt, S.C.; Remaut, K. Effect of hyaluronic acid-binding to lipoplexes on intravitreal drug delivery for retinal gene therapy. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 103, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Correia, A.R.; Sampaio, I.; Comparetti, E.J.; Vieira, N.C.S.; Zucolotto, V. Optimized PAH/Folic acid layer-by-layer films as an electrochemical biosensor for the detection of folate receptors. Bioelectrochemistry 2020, 137, 107685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaei, S.N.; Derbali, R.M.; Yang, C.; Superstein, R.; Hamel, P.; Chain, J.L.; Hardy, P. Co-delivery of miR-181a and melphalan by lipid nanoparticles for treatment of seeded retinoblastoma. J. Control. Release 2019, 298, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugh, H.; Sood, D.; Chandra, I.; Tomar, V.; Dhawan, G.; Chandra, R. Role of gold and silver nanoparticles in cancer nano-medicine. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 1210–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, S.; Li, C.; Hao, Y. Rosiglitazone Gold Nanoparticles Attenuate the Development of Retinoblastoma by Repressing the PI3K/Akt Pathway. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. Lett. 2020, 12, 820–826. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Zhuang, Q.; Ji, T.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Jia, H.; Liu, Y.; Du, L. Multi-functionalized chitosan nanoparticles for enhanced chemotherapy in lung cancer. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 195, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Tang, C.; Yin, C. Combination antitumor immunotherapy with VEGF and PIGF siRNA via systemic delivery of multi-functionalized nanoparticles to tumor-associated macrophages and breast cancer cells. Biomaterials 2018, 185, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, T.F.; Remaut, K.; Deschout, H.; Engbersen, J.F.; Hennink, W.E.; Van Steenbergen, M.J.; Demeester, J.; De Smedt, S.C.; Braeckmans, K. Coating nanocarriers with hyaluronic acid facilitates intravitreal drug delivery for retinal gene therapy. J. Control. Release 2015, 202, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, J.J.; Runge, J.J.; Singhal, S.; Nims, S.; Venegas, O.; Durham, A.C.; Swain, G.; Nie, S.; Low, P.S.; Holt, D.E. Intraoperative near-infrared fluorescence imaging targeting folate receptors identifies lung cancer in a large-animal model. Cancer 2017, 123, 1051–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.; Ke, J.; Zhou, X.E.; Yi, W.; Brunzelle, J.S.; Li, J.; Yong, E.-L.; Xu, H.E.; Melcher, K. Structural basis for molecular recognition of folic acid by folate receptors. Nature 2013, 500, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Moraes Profirio, D.; Pessine, F.B.T. Formulation of functionalized PLGA nanoparticles with folic acid-conjugated chitosan for carboplatin encapsulation. Eur. Polym. J. 2018, 108, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramishetti, S.; Hazan-Halevy, I.; Palakuri, R.; Chatterjee, S.; Naidu Gonna, S.; Dammes, N.; Freilich, I.; Kolik Shmuel, L.; Danino, D.; Peer, D. A combinatorial library of lipid nanoparticles for RNA delivery to leukocytes. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1906128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.; Ashwanikumar, N.; Robinson, E.; Xia, Y.; Mihai, C.; Griffith, J.P.; Hou, S.; Esposito, A.A.; Ketova, T.; Welsher, K. Naturally-occurring cholesterol analogues in lipid nanoparticles induce polymorphic shape and enhance intracellular delivery of mRNA. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yu, X.; Dai, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Qi, S.; Liu, L.; Lu, L.; Luo, Q.; Zhang, Z. Melittin-lipid nanoparticles target to lymph nodes and elicit a systemic anti-tumor immune response. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lingayat, V.J.; Zarekar, N.S.; Shendge, R.S. Solid lipid nanoparticles: A review. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. Res. 2017, 2, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Paliwal, R.; Paliwal, S.R.; Kenwat, R.; Kurmi, B.D.; Sahu, M.K. Solid lipid nanoparticles: A review on recent perspectives and patents. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2020, 30, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, C.; Jo, M.; Park, Y.H.; Kim, J.H.; Han, J.Y.; Lee, K.W.; Kweon, D.-H.; Choi, Y.J. Enhancing the oral bioavailability of curcumin using solid lipid nanoparticles. Food Chem. 2020, 302, 125328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, I.; Pandit, J.; Sultana, Y.; Mishra, A.K.; Hazari, P.P.; Aqil, M. Optimization by design of etoposide loaded solid lipid nanoparticles for ocular delivery: Characterization, pharmacokinetic and deposition study. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 100, 959–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crommelin, D.J.; van Hoogevest, P.; Storm, G. The role of liposomes in clinical nanomedicine development. What now? Now what? J. Control. Release 2020, 318, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, K.; Rappolt, M.; Mao, L.; Gao, Y.; Li, X.; Yuan, F. The stabilization and release performances of curcumin-loaded liposomes coated by high and low molecular weight chitosan. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 99, 105355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, F.; Fan, W. Cisplatin Nano-Liposomes Promoting Apoptosis of Retinoblastoma Cells Both In Vivo and In Vitro. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. Lett. 2020, 12, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Goyal, A.K.; Rath, G. Recent advances in metal nanoparticles in cancer therapy. J. Drug Target. 2018, 26, 617–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallares, R.M.; Thanh, N.T.K.; Su, X. Sensing of circulating cancer biomarkers with metal nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 22152–22171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arshad, R.; Pal, K.; Sabir, F.; Rahdar, A.; Bilal, M.; Shahnaz, G.; Kyzas, G.Z. A review of the nanomaterials use for the diagnosis and therapy of salmonella typhi. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1230, 129928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remya, R.R.; Rajasree, S.R.R.; Aranganathan, L.; Suman, T.Y.; Gayathri, S. Enhanced cytotoxic activity of AgNPs on retinoblastoma Y79 cell lines synthesised using marine seaweed Turbinaria ornata. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2016, 11, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remya, R.; Rajasree, S.R.; Suman, T.; Aranganathan, L.; Gayathri, S.; Gobalakrishnan, M.; Karthih, M. Laminarin based AgNPs using brown seaweed Turbinaria ornata and its induction of apoptosis in human retinoblastoma Y79 cancer cell lines. Mater. Res. Express 2018, 5, 035403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromma, K.; Chithrani, D.B. Advances in Gold Nanoparticle-Based Combined Cancer Therapy. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Saini, M.; Dehiya, B.S.; Sindhu, A.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, R.; Lamberti, L.; Pruncu, C.I.; Thakur, R. Comprehensive survey on nanobiomaterials for bone tissue engineering applications. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, R.; Sohail, M.F.; Sarwar, H.S.; Saeed, H.; Ali, I.; Akhtar, S.; Hussain, S.Z.; Afzal, I.; Jahan, S.; Shahnaz, G. ZnO-NPs embedded biodegradable thiolated bandage for postoperative surgical site infection: In vitro and in vivo evaluation. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kalmodia, S.; Parameswaran, S.; Ganapathy, K.; Yang, W.; Barrow, C.J.; Kanwar, J.R.; Roy, K.; Vasudevan, M.; Kulkarni, K.; Elchuri, S.V. Characterization and molecular mechanism of peptide-conjugated gold nanoparticle inhibiting p53-HDM2 interaction in retinoblastoma. Mol. Therapy-Nucleic Acids 2017, 9, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Nanostructure | Key Feature | References |

|---|---|---|

| Gold NPs | Due to selective light absorption by the administered gold NPs, photoacoustic image contrast from the tumor regions was improved. | [73] |

| Gold nanoclusters | The signal enhancement by >500 gold atoms in each nanocluster enabled laser ablation (LA) coupled to inductively coupled plasma—mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) to image the antigens (MT 1/2 and MT 3) using a laser spot size as small as 4 μm. | [74] |

| Gold nanorods | The effectiveness of PT-OCT, along with Au nanorods, to picture the distribution in the mouse retina of both endogenous and exogenous absorbers. | [75] |

| Magnetic NPs | In magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies, the nanoparticles displayed perfect negative contrast and demonstrated their biocompatibility without cytotoxicity (5–100-μg/mL Fe3O4 NPs) to both regular and cancer cells. | [76] |

| Quantum dots | The preservation of QDs in the cryogenically injured corneal endothelium mouse model eyes was from 3 to 48 h post-cell injection on the posterior surface but not in the non- injured stable control eyes. | [77] |

| Carbon nanomaterials | The quantitative identification of the DNA methylation ratios was only calculated by methylated 5’-cytosine-phosphoguanosine (CpG) repeat oligonucleotides (60 mers) with various methylation ratios by carbon nanofilm electrodes. | [78] |

| Multi-functional NPs | In vivo and in vitro, mesoporous Au nanocages (AuNCs) combined with Fe3O4 nanoparticles improved photoacoustic (PA), ultrasound (US), and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, which was beneficial for diagnosis and efficacy monitoring. | [79] |

| Nanocarrier | Key Feature | References |

|---|---|---|

| Melaphalan NPs | The double-emulsion method was utilized to reduce melphalan spilling during the fabrication process and resulting in targeted delivery | [102] |

| Galactose NPs | In RB, sugar moieties in the form of lectins are highly overexpressed as compared to healthy cells.Therefore, galactose is a mean of targeting for achieving efficacious results. | [103] |

| Hyaluronic acid NPs | Nonviral polymeric gene DNA complex-based nanomedicines were coated electrostatically with hyaluronic acid (HA) for providing an anionic hydrophilic coating for improved intravitreal mobility. | [104] |

| Folic acid NPs | Chitosan NPs (CNPs)and loaded doxorubicin (DOX) were synthesized and conjugated with folic acid for targeted delivery against RB. | [105] |

| LipidNPs | Switchable lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) were synthesized for the codelivery of melphalan and miR-181, having 93% encapsulation efficiency against RB. | [106] |

| SilverNPs | Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) via rapid methodology from natural sources of brown seaweed Turbinariaornate and its cytotoxic efficacy were determined against RB cells. | [107] |

| Gold NPs | In vivo and in vitro, mesoporous Aunanocages (AuNCs) combined with Fe3O4NPs improved photoacoustic, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging, which was beneficial for diagnosis and therapy. | [108] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arshad, R.; Barani, M.; Rahdar, A.; Sargazi, S.; Cucchiarini, M.; Pandey, S.; Kang, M. Multi-Functionalized Nanomaterials and Nanoparticles for Diagnosis and Treatment of Retinoblastoma. Biosensors 2021, 11, 97. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/bios11040097

Arshad R, Barani M, Rahdar A, Sargazi S, Cucchiarini M, Pandey S, Kang M. Multi-Functionalized Nanomaterials and Nanoparticles for Diagnosis and Treatment of Retinoblastoma. Biosensors. 2021; 11(4):97. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/bios11040097

Chicago/Turabian StyleArshad, Rabia, Mahmood Barani, Abbas Rahdar, Saman Sargazi, Magali Cucchiarini, Sadanand Pandey, and Misook Kang. 2021. "Multi-Functionalized Nanomaterials and Nanoparticles for Diagnosis and Treatment of Retinoblastoma" Biosensors 11, no. 4: 97. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/bios11040097